Department of Epidemiology

Learn how we advance public health globally by researching the frequency, distribution, and causes of human disease, and shaping health policies and practices.

677 Huntington Avenue

Kresge, 9th Floor,

Boston, MA 02115

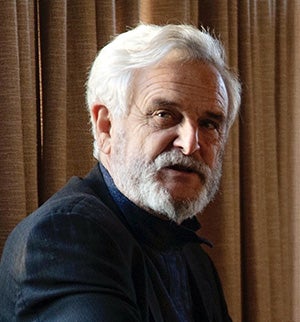

50 Years Ago: Q&A with Alumnus Raymond Neutra

September 23, 2024—Raymond Neutra ’74, DrPH, has had a public health career in environmental medicine and epidemiology holding academic appointments at various academic institutions including Harvard and University of California systems as well as public sector leadership roles, in particular from 1980-2007 he was Chief of the Division of Environmental and Occupational Disease Control (DEODC) at the California Department of Health Services (CDHS), later California Department of Public Health. He was also founding president of the International Society of Environmental Epidemiology. Currently he is the President of the Neutra Institute for Survival Through Design, continuing in his father’s legacy, to promote creative research and design that benefits people and the planet. Here he answers questions about his time as a graduate student and offers advice to current students.

What you will do with epidemiology depends on your personality, skills, and the external opportunities which will arise. Listen to your heart when you respond to what courses attract you.

Take us back your student days at the Harvard School of Public Health… What are your recollections from your time in the epidemiology department? What was the environment like? How would you describe the (academic) atmosphere?

I came to HSPH International House in early July 1968 having finished my two years of mandatory military service in the US Public Health Service on the Navajo Indian Reservation at Crown Point New Mexico. My first wife Dr Marian Neutra was pregnant with our second son Matthew and with our one-year-old first son Justin we had driven our Volvo station wagon across the country. We had a few quiet months with the kindly house mother Mrs. Penrose to enjoy the Back Bay, and I seem to remember taking music lessons at the Berklee School of Music. I had fallen in love with epidemiology during a CDC weeklong training course on TB control, which was one of my duties on the reservation. The gathering of evidence to guide policies that benefitted the entire population regardless of political power or wealth squared with the values I had grown up with in my father’s architectural live-work space in Los Angeles. I came to get an MPH, but as that year came to a close it was clear that one year was not enough and I was lucky to get some kind of government scholarship that fully covered my DrPH studies.

The 10-minute walk from the Fens up tree-lined Avenue Louis Pasteur to the HMS/HSPH campus remains a vivid memory as does the friendships at International House with the likes of Noel Weiss and Otto Steenfeldt-Foss from Norway. Contacts with social epidemiologist Alexander Leighton, nutritionist Jean Mayer, and ergonomics and injury specialist Ross McFarland broadened my education beyond the stimulating statistics courses by Jane Worcester, Marge Drollette and the epidemiology of Brian MacMahon and Olli Miettinen. Olli’s perspectives on confounding and effect modification were particularly influential and later became a topic that continued with my doctoral student at UCLA, Sander Greenland. Ascher Segall’s course on medical education has served me well not only during my later time’s teaching at Harvard and UCLA, but also in crafting public communications at the California Department of Public Health. Secretary George Romney’s proposal to solve housing problems with prefabricated houses during the Nixon administration, stimulated Ross McFarland and me to write a paper on home, unintended injuries, and how the careful design of such mass-produced houses could avoid such injuries, just as seatbelts and airbags in cars could avoid them in those vehicles. This was my first public health publication. Well-being and the designed environment was the central theme in my architect father’s career. Now fifteen years after retiring from environmental epidemiology, I am heading up a non-profit that my father started in 1962 to help those interested in researched responsible design. If you are curious visit The Neutra Institute for Survival Through Design.

What was the thesis writing process like for you? How did you pick the topic for your thesis “Epidemiological Studies of Eclampsia?” Were there any challenges? Any unexpected surprises? What lead to your studies in Cali, Colombia?

One day in my first doctoral year, the elevator door on the first floor opened and my mentor Dieter Koch-Weser walked out and paused, asking “Oh! Would you have any interest in doing your thesis in Cali, Colombia? The Rockefeller Foundation has asked Dean Howard Hiatt to send someone from HSPH to join a WHO health planning team in Cali. But if you are interested, you need to fly down there week after next.” “Hell yes! “I answered, “but I better check with my wife first, we are expecting our third son in May.” Marian was up for the adventure and we ended up spending three happy years hosted by Tulane’s International Center for Medical Research and Training. I seem to remember that the young Ken Rothman came to visit us while we were there. The topic changed from tuberculosis to Eclampsia of Pregnancy. After a few months of monthly reports to Brian MacMahon he wrote me that I was too far away to closely supervise, I should do the best I could and feel free to ask for advice on any pressing issues. At the end of the three years, I was offered an Assistant Professorship in Preventive Medicine at Harvard Medical School and then a fellowship in Dean Hiatt’s new Center for Health Policy. I was working with the young Milt Weinstein and Howard Fineberg who had recently completed a course in quantitative decision analysis with Howard Raiffa at the main Harvard campus. Along with Barbara McNeil and Duncan Neuhauser we wrote a textbook on Clinical Decision Analysis. We were learning how epidemiological probabilities could be combined with the valuation of outcomes to derive a reasoned course of action.

Dean Hyatt and Fred Mosteller as well as Dr. John Bunker who was on sabbatical from Stanford, decided to form a seminar to create a book of case studies of applying this approach to surgery. What followed was a series of delightful monthly dinners and talks at the Harvard faculty club including such colleagues as Shan Cretin, who helpfully crossed paths with me again later in my career in California.

Around the same time I was teaching a course on healthy design with Dr. John Zeisel at the Boston Design Center and also completing a chapter for a medical anthropology book on hysteria and temporal lobe epilepsy on the Navajo. While all this was going on I was completing the analysis of my Eclampsia studies under the careful guidance of George Hutchison who had taken over the role of thesis advisor when Brian McMahon was on sabbatical. Working late while submitting punch cards for the analysis of my data I would leave around 10:00 PM and look up at the 13th story of the building to see George burning the midnight oil. For every page of my thesis, he returned a page of carefully written suggestions. It seemed the project would never end, but it finally did.

What advice would you give to current students in the department? Is there something you wished you’d known during your time as a student?

Although I subsequently went on to get a tenured teaching and research position at UCLA school of public health, I realize now that my subsequent career at the California public health department was more suited to satisfy my restless sense of curiosity. It was like being in a public health emergency room that generated evidence based policy challenges ranging from the prevention of childhood lead poisoning, how to respond to multiple chemical sensitivity to possible threats from magnetic fields in California schools. This is relevant to any advice I might give to someone starting out in epidemiology. What you will do with epidemiology depends on your personality, skills, and the external opportunities which will arise. Listen to your heart when you respond to what courses attract you. This will give you a hint as to your aptitudes. Are they leading you to a narrow academic disciplined career or to applying the knowledge and skills you’ve acquired in an unforeseen direction.

–Coppelia Liebenthal