A gift to share the transformative impact of public health education

Steve Shama MPH ’74, MD, honors the profound impact of public health education in his life by endowing a scholarship fund.

For Steve Shama, Harvard Chan School was a profound awakening. He didn’t plan to study public health. Shama was a young occupational health physician when a mentor suggested that an MPH would help further his career.

“Medicine, to me, was how do you take care of thyroid disease, or heart disease. You treat a specific thing,” he recalls. “In public health, everything is a story. You do this because people are dying in far off lands, or because communities are suffering in the United States. The classes, the conversations, being with people from every corner of the world—everything was amazing.”

Discovering universal empathy

Shama grew up in Brooklyn, the son of a Yemeni Jewish father who never finished grade school and a mother from Hungary who finished high school but not beyond. He was raised with “a feeling of giving back to the world, even if it was never spoken outright.” At the School of Public Health, that spirit blossomed: “All the experiences you get bring out who you are. Meeting people from Africa, the Middle East, from places I’d never encountered, I realized; they’re just like me. It was humbling.”

The lessons went far beyond epidemiology or statistics. “I learned the importance of empathy, the kind that stretches beyond your own borders and community. To really make a difference, you need humility and universal empathy,” says Shama. This awakening changed his professional life, steering him not just to treat individual patients, but to think about how to improve health on a population level. “The MPH degree is not just facts; it’s an awakening in you of how you can make the world better because you have lived.”

I decided to give because I realized that there were some people who have this beautiful dream to make this world a better and healthier place. They’re passionate about it, but they don’t have the funds. I wanted to make sure that Harvard Chan School had enough funds to do the best they could to attract these people.

A legacy of opening doors

Shama’s medical practice shifted to dermatology, and he began giving talks on empathy. Shama strives to live, as he puts it, “One moment short of a tear.” That means, to focus on topics of impact, that bring out strong feelings in himself and others. And one thing Shama feels very deeply is gratitude for the way that studying public health broadened his worldview.

This gratitude, and the hope to open the world for others as it was opened for him, inspired Shama’s decades-long commitment to financial aid. “I decided to give because I realized that there were some people who have this beautiful dream, to make the world a better and healthier place. They’re passionate about it, but they don’t have the funds. I wanted to make sure that Harvard Chan School had enough funds to do the best they could to attract these people.”

Shama’s latest gift establishes the endowed Steven K. Shama, MPH ’74 and Jeannie Lindheim Shama Financial Aid Fund. “I give for memories. I give for feelings. If there’s someone out there who can’t attend because they can’t afford the last $5,000, I want to help. No matter how much you give, you do it because you feel that your efforts can make a difference. And the School leaves you with that feeling.”

As for his decision to include Harvard Chan School in his will, Shama says it’s as much about legacy and humility as about philanthropy. “You reach a point where you realize, we’ve left enough for our children—and then, what? We give to organizations that made a difference in our lives. For me and my wife, it’s about ensuring that opportunity continues for others. I hope students see my name and my story, and realize the path is open to them too.”

Last Updated

Harvard Chan DrPH program celebrates 10 years preparing public health leaders

Brenda Onguti, DrPH ’23, began her career as a pharmacist in her home country of Kenya. Working with HIV-positive patients from poor backgrounds, she noticed that they were particularly vulnerable to infectious diseases, and wondered how she could address the issue from a broader policy and systems perspective. Inspired to transition to the field of public health, she completed an MPH degree—and then found herself considering her next step.

“Once I graduated, I knew that I needed to go back [to school] and do a doctorate. But I didn’t want just to learn more research, to do more studies. What I wanted was to know, how do I bridge the evidence-practice gap?” Onguti said. “We currently have such great high-impact interventions within public health that can elevate people’s health and well-being, but often it’s not really being practiced.”

Her research led her to the Doctor of Public Health (DrPH) program at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, which is designed to prepare mid-career public health professionals for high-level leadership positions in a wide range of organizations, from hospitals to nonprofits to government agencies. Over 3-4 years, students hone their skills by taking courses, participating in field immersion experiences, and completing a doctoral project and thesis.

The program, which marked its 10th anniversary in 2024, combines the research emphasis of a PhD degree with the practical application involved in an MPH degree, according to Richard Siegrist, program faculty director and senior lecturer on health care management. “The DrPH program blends the best of both worlds,” he said. “It’s a place where people can come get a really good education and then go out there and be much more impactful than before.”

He said the program, which has accepted only 10 students per year in the past, accepted 15 for the 2024-25 academic year. “Expanding the cohort size has enabled us to admit more highly qualified students and will improve the learning experience in our DrPH-specific courses,” said Siegrist. “The larger group will enhance classroom dynamics and deepen peer learning.”

Along with passing the 10-year mark and growing in size, the DrPH program is also celebrating several significant donations (see sidebar) that will help provide support in the years to come.

Classroom work, field work

Coursework in the DrPH program covers a variety of subjects, including leadership, innovation, financial management, and communication. At the core of the curriculum is a sequence of courses that focuses on developing leadership skills on three different levels—individual, organization, and system.

“By the time students complete our DrPH courses, they have a clearer sense of how they show up as leaders—what’s working for them and what may need to evolve,” said Siegrist. He added, “These are accomplished mid-career professionals who’ve made the bold and reflective decision to step back from their current roles, deepen their leadership capabilities, and return to their work with greater impact. It’s a vulnerable and deliberate act—pausing a well-established identity in order to reshape it with intention and purpose.”

Siegrist noted that the in-person experience is an important aspect of the program. “Many DrPH programs are offered primarily online,” he said. “At Harvard Chan School, you get to know people in your cohort much better. You get to know the faculty much better. You are more immersed in the School, and you have the ability to take on leadership roles,” he said.

Field immersions are another major component of the DrPH program, highlighted by an 8- to 10-week summer immersion and an eight-month doctoral project in which students work with a host organization to address a critical public health issue. Both opportunities give students the chance to apply concepts learned in their coursework to real-world settings.

The student experience

Prior to starting the DrPH program in July 2021, Kevin Linn, DrPH ’25, worked in strategic health policy, with a focus on improving access to cancer care for Indigenous communities in Canada. For him, participating in the program meant having a chance to apply what he’d learned in his work in an academic setting, as well as delve into other complex health policy challenges at a global level.

For his doctoral project, he did a research fellowship at Gates Ventures—the private office of philanthropist Bill Gates—where he explored the health effects of climate change, the role of philanthropy in addressing the issue, and methods for sparking innovation. To conduct his research, he connected with more than a dozen philanthropic and global health organizations around the world to learn about their work. “We found that philanthropies lacked organizational strategy and were struggling to define and evaluate their climate change and health work,” he said.

In his thesis, Linn developed a taxonomy of climate change and health solutions pathways to support organizations. Each pathway is defined by a description of climate change drivers, the impact of drivers on individual pathophysiology or social systems, health outcomes, relevant adaptation and mitigation solutions, and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets. As a framework, the taxonomy aids strategic decision-making, and supports coordination and collaboration within and between organizations.

A desire for impact

Another student in the 2025 DrPH graduating cohort, Erika Willacy, came to the program after a dozen years at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where she worked in global health. She had begun to question whether certain global health efforts were having enough impact. For instance, during the COVID pandemic, she recalled being at a meeting where colleagues were discussing the importance of equitable vaccine distribution. At the time, distribution in the U.S. was climbing rapidly, while in Africa and some parts of Asia it was moving much more slowly, “almost to the point of barely being perceptible,” she said. As weeks passed and the situation remained basically the same, she found herself becoming increasingly frustrated.

“I really started to think about how much impact we were really having if these things were being discussed and maybe even being put in reports, but at the end of the day were not actually being translated into action,” she said. “That is a big part of what generated my interest in applying to the DrPH program.”

She said that the program has helped her think about how to accelerate change when it comes to complicated public health problems, “from how to set up the culture of a team that I would lead, to how to take a complex problem apart and think about it systemically, to how to address that complexity in order to overcome a particular challenge.”

For her doctoral project, she created a framework to help public health institutes around the world—entities similar to the CDC—achieve greater impact. To develop the framework, she interviewed public health experts around the world and conducted several case studies. One of the case studies included details on Bangladesh’s response to a rise in deaths due to dengue fever, a disease spread via mosquitoes. Willacy found that even though there are strong surveillance systems across Bangladesh to detect dengue, gaps in systemic functioning and collaboration meant that preventive measures were not taken. National governments and community governments did not necessarily have good working relationships with one another—which meant, for example, that one community might take steps to reduce standing water where mosquitoes breed, but another might not, making overall efforts to reduce the spread of dengue less effective.

In her doctoral thesis, Willacy also outlined several “strategic accelerators” to overcome such roadblocks, such as focusing on creating systems that understand when to pivot and evolve to new and changing contexts. She also encouraged government public health systems to utilize the expertise of populations and invest in true collaboration with them to optimize progress.

Alumni perspectives

During Onguti’s time at Harvard Chan School, she became particularly interested in implementation science—learning how to take a public health intervention that has been tested in a research setting and bringing it into practice. For her doctoral project, which was funded by the Tessa Jowell Research Fellowship through the Harvard Ministerial Leadership Program, she focused on preconception care in Zambia, identifying gaps and opportunities in the health system in order to make recommendations for integration.

Since graduating, Onguti has been making good on her goal to bridge the evidence-practice gap. For example, she has worked as a consultant for the nonprofit organization Jhpiego, developing a strategy to scale group antenatal care across low- and middle-income countries globally. To address the shortage of maternal health care providers, pregnant women of similar gestational age receive care in a group setting where they can discuss common challenges with each other, while also having access to clinicians. “It’s an empowering [experience], being able to get solutions from other women and support from your health provider,” she explained.

Reflecting on her overall experience in the DrPH program, Onguti said that a highlight was the mentoring she received. “There’s such a great support system by the professors,” she said. “Having an open-door policy so that you could talk to your professors—and them being able to advise you not only in terms of the course or program itself, but on other aspects of life—really stood out to me.”

Stephanie Kang, DrPH ’21, grew up wanting to become a leader in the health care field, but she felt that meant going to medical school to become a doctor. While working toward that goal, she came across information about the DrPH degree and immediately shifted gears.

“As my understanding of healing evolved—from focusing solely on medical services to recognizing the conditions that make and keep people sick—I began searching for a program that could equip me with the tools and skills to address those deeper systemic issues. That’s when I learned about the DrPH program and immediately recognized it as a unique space for intentional, practice-based learning that I couldn’t find anywhere else,” she said. “So, I made the decision to continue working in two different community-based non-profits full-time and enrolled in a part-time master’s program to better position myself for the DrPH. I knew this was the kind of training I needed to lead change in a more meaningful way.”

She decided to apply to the DrPH program at Harvard Chan School because of its unique approach to leadership training—providing not just courses, but also other resources such as executive coaching. Each student is paired with a professional coach outside the School who has experience working with C-suite executives and helps them pursue their career goals.

During Kang’s second year, she received a job opportunity to work in the office of U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) as a health policy fellow, focusing on universal health care. With the encouragement of her program advisor, she moved to Washington, D.C. for the position while finishing up her coursework remotely, and ended up writing her doctoral thesis on the same topic. She currently serves as the inaugural deputy assistant commissioner of health equity in the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

“When you’re in leadership roles, especially in fast-paced environments, it’s incredibly hard to pause and reflect on your purpose—on why you do the work,” Kang said. “The DrPH program gave me a rare space to step back, connect deeply with others who had been through similar challenges, and ground myself in the kind of leader I wanted to be—especially in moments of difficulty and doubt.”

Generous donations aimed at reducing financial barriers for DrPH students

Harvard Chan School has received several significant gifts from generous donors for the DrPH program.

The Robert and Ardis James Foundation recently gave $1 million. And another $500,000 was contributed by an anonymous donor.

Both gifts will support financial aid. And both are being matched dollar-for-dollar, thanks to another anonymous donor with a longstanding commitment to removing financial barriers for exceptional students. In 2023, that donor said they’d match all financial aid gifts to the DrPH program up to $2 million. Previously, the donor had provided matching funds for several gifts from multiple donors totaling more than $500,000. With the two new gifts totaling $1.5 million, the challenge is now complete.

“These generous donations will enable us to significantly reduce financial barriers for students,” said DrPH program director Rick Siegrist. “Investing in this program can make a powerful impact, as demonstrated by the accomplishments of our alumni. They have taken on leadership roles in major government health agencies, led innovative initiatives in domestic and international organizations, and shaped influential policy and operational efforts.”

Last Updated

Featured in this article

From research to reality: Public health in our daily lives

Public health surrounds us in ways we rarely notice—from the lead-free water we drink to the nutritious food we eat and the clean air we breathe. These everyday protections stem directly from groundbreaking research at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health that safeguards millions of lives simultaneously.

While doctors treat one patient at a time, Harvard Chan researchers transform entire systems—revolutionizing HIV treatment, preventing cancer, reducing gun violence, and preparing for future pandemics. The School’s faculty have demonstrated the dangers of air pollution leading to tighter clean air standards, pioneered the field of cancer genetics, illuminated the impacts of racism on health, and played crucial roles in global health initiatives from polio eradication to humanitarian disaster response.

For over a century, Harvard Chan School has worked toward a world where everyone can thrive. This vital work depends on support to continue its impact—because public health isn’t just a discipline, it’s a goal.

To support life-saving research and public health solutions, visit hsph.me/whygive.

Last Updated

Endowed professorships awarded to two IID faculty members

IID is thrilled to announce the appointment of endowed professorships to faculty members Dr. Flaminia Catteruccia and Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett-Helaire, courtesy of generous philanthropic contributions.

Dr. Catteruccia received the Irene Heinz Given Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases. Her laboratory, the Catteruccia Lab, strives to help the creation of new, effective tools for mosquito and malaria control by examining the molecular and behavioral parameters that are key to the ability of Anopheles mosquitoes to transmit malaria, with special emphasis on reproductive biology and vector-Plasmodium interactions. Their work expands beyond Harvard’s walls with a key component of their research conducted through fieldwork and collaboration with partners in Africa.

Dr. Corbett-Helaire received the Melvin J. and Geraldine L. Glimcher Assistant Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases. In order to increase global pandemic preparedness, the Corbett Lab focuses on vaccine development and therapeutic antibody discovery for coronaviruses and other emerging and re-emerging viruses. The highly collaborative team studies the immune landscape of viral surface proteins and deciphers the influence of immune responses on the clinical outcome following natural viral infection to design and assess novel vaccine concepts.

Last Updated

Understanding the Health Impacts of Wildfires

A gift from the Spiegel Family Fund is enabling researchers across multiple institutions—including Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health—to investigate the effects of wildfires on human health

In January 2025, the city of Los Angeles was devastated by the Palisades and Eaton wildfires. Spreading rapidly across neighborhoods, the fires killed 29 people, destroyed more than 16,000 homes and buildings, and exposed millions of people to toxic smoke—even those living hundreds of miles away. In the aftermath of the fires, residents and first responders face concerns about the health hazards of their changed environment.

Thanks to a gift from the Spiegel Family Fund, a consortium of researchers from six universities are collaborating to investigate and better understand the short- and long-term effects of wildfires and help reduce the risk of harmful exposures. The Spiegel Family Fund’s gift is also inspiring other donors to support the study.

The Los Angeles Fire Human Exposure and Long-Term Health Study (L.A. Fire HEALTH Study)—led by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California; Stanford University; the University of California, Los Angeles Fielding School of Public Health; the University of California, Davis; and the University of Texas at Austin—aims to examine what types of pollutants are present in the environment, where they are located, and the quantity that persists over time. Bringing together scientists with expertise in data science, health outcomes, wildfire risk assessment, and environmental exposure assessment, the study is measuring the respiratory, neurological, cardiovascular, reproductive, and immune system effects of wildfires over 10 years.

The L.A. Fire HEALTH Study is unique for many reasons, including its urgency and scope. Because so little is known about wildfire health effects over time—such as the risk of developing chronic conditions like asthma, heart disease, and stroke—the findings will provide much-needed data to help inform decisions about public health and safety.

Evan Spiegel, who established the Spiegel Family Fund in 2017, grew up in Pacific Palisades and currently lives in Los Angeles with his family. His strong connection to California spurred him to support the project.

Spiegel decided to fund the study in the hopes that it could propel local recovery efforts and reveal valuable knowledge that will help people around the world affected by wildfires.

“We are not the first community to face a megafire. We will not be the last,” Spiegel wrote in a letter to the City of Los Angeles after the wildfires. “But we will use our strength, our ingenuity, and our love to create again and anew.”

A Living Laboratory

Moving quickly once the fires were under control, researchers outfitted a van into a mobile collection lab where they could quickly gather and test samples from affected neighborhoods. The team retained samples of ash and other contaminants from the interiors of 50 homes, along with data gathered from air pollution sensors. In addition to showing the effects of the pollutants, the samples will also help researchers examine how building design and air filtration systems handle these contaminants.

“This rapid mobilization of scientists across so many universities, all with a common goal of helping the people of Los Angeles through this crisis, simply would not have been possible without the support from the Spiegel Family Fund,” says Joe Allen, professor of exposure assessment science in the Department of Environmental Health at Harvard Chan School and director of the Harvard Healthy Buildings Program, who is co-leading the consortium’s efforts at measuring contaminants in air, water, soil, dust, and ash.

On its own, wildfire smoke is dangerous due to its chemical makeup and particulate matter. Its composition varies depending on the source of the fire, its intensity, and how it interacts with conditions in the atmosphere. In urban areas like Los Angeles, additional contaminants (such as asbestos and microplastics) from burning cars, buildings, and furniture become suspended in the air and water.

Preliminary findings from the L.A. Fire HEALTH Study are already leading to interventions. Initial results indicated that firefighters involved in the Palisades and Eaton fires exhibited higher concentrations of lead and mercury in their blood cells compared to those who had battled earlier forest fires in less densely populated regions. Prior to this study, scientists only looked for the presence of harmful chemicals in the air, not inside human cells. With this new information, doctors from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center were able to treat the firefighters for this exposure sooner—and it could help medical professionals in Los Angeles and elsewhere diagnose and treat more people earlier following future fires.

In addition, the study has been able to rapidly disseminate test results from air and water and provide actionable steps people can take to stay safe—including releasing data briefs and guides, such as how to reduce risk of wildfire smoke at home, and leading town halls across Los Angeles.

By monitoring health outcomes over time, researchers hope to equip everyone affected by wildfires—residents, first responders, fellow scientists, and nonprofits providing disaster relief—with the tools they need. “One of our biggest priorities is to provide communities with information based on sound scientific evidence so that they can make the best decisions possible,” says Nadeau.

Last Updated

Long-term, multi-institutional study on health impacts of Los Angeles wildfires launched

In an unprecedented collective scientific effort to understand the short- and long-term health impacts of wildfires, researchers from four universities have launched a 10-year study of the Los Angeles fires. The wildfires that began in early January 2025 killed 29 people, destroyed more than 16,000 structures, and exposed millions to toxic smoke.

The research aims to evaluate which pollutants are present, at what levels, and where, and to assess the respiratory, neurological, cardiovascular, reproductive, and immune system impacts of the wildfires.

The Los Angeles Fire Human Exposure and Long-Term Health Study (L.A. Fire HEALTH Study) is being launched with the support of a visionary gift from the Spiegel Family Fund. The multi-institutional collaboration is a consortium led by researchers from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, University of California, Davis, and the University of Texas at Austin with expertise in environmental exposure assessment, health outcomes, wildfire risk assessment and management, and data science.

“This was an environmental and health disaster that will unfold over decades,” said Kari Nadeau, John Rock Professor of Climate and Population Studies and chair of the Department of Environmental Health at Harvard Chan School, professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, and practicing physician at Beth Isreal Deaconess Hospital. “By bringing together experts from across multiple institutions and disciplines, we can rigorously examine the health effects from the wildfires’ toxic particles and gases that have spread hundreds of miles beyond the fire zones and provide the communities with this information in real time.”

Wildfire hazards

Wildfires in Los Angeles and other urban areas present unique hazards as buildings, cars, and products are incinerated, exposing people to particulate matter, gases, chemicals, heavy metals, asbestos, PFAS, microplastics, and other toxic pollutants. They settle out of the air into soil and dust and can become resuspended during recovery and rebuilding efforts. Water quality can also be affected.

The potential health impacts on millions of Los Angeles residents from exposure are many and include:

- Acute respiratory symptoms and worsening of lung conditions, including asthma and COPD

- Neurological impacts, including headaches and cognitive issues

- Cardiovascular effects, including increased risk of heart disease and stroke

- Immune system disruption

- Reproductive health concerns

- Increased cancer risk

“Air pollutants, such as those from wildfires, are linked to short-term health problems such as asthma and longer-term ones such as Alzheimer’s disease,” said Anthony Wexler, director of the Air Quality Research Center at UC Davis.

“Here in Los Angeles, we know that communities need accurate and timely information about what individuals and families can do to prevent and mitigate health effects from fires, both in the near- and long-term,” said Michael Jerrett, Jonathan Fielding Chair in Climate Change and Public Health, and professor in the Department of Environmental Health Sciences at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. “With this study we can supply sound science to help residents repopulate and rebuild their neighborhoods safely, and for the first time, we can learn about the long-term health effects of wildfires.”

Study aims

The L.A. Fire HEALTH Study has two primary objectives: First to examine which pollutants are present, at what levels, where, and how they change over time; and second to determine if the fires and aftermath are associated with chronic health effects in the nearby population.

In the study’s first phase, teams are mapping and understanding exposures during the fires, including emissions from the burning of vegetation and buildings and the composition of pollutants in the wildfire smoke. As part of the air sampling effort, a mobile van will be deployed, equipped with advanced measurement technologies that can measure the chemical composition of particulate matter and gases in real time.

A study of homes in the area will include monitoring indoor and outdoor air, drinking water, house dust, and soil samples, and assessing the role that building design and filtration plays in limiting infiltration of wildfire pollutants. A novel approach to estimate smoke infiltration into homes will also be used. “Building materials can absorb infiltrated smoke, creating the potential for exposure to harmful compounds for weeks and months after a wildfire. By taking measurements inside and outside of homes, we can quantify how building materials impact exposure and provide insights on when it is safe to return to homes in areas impacted by wildfires,” said Lea Hildebrandt Ruiz, associate professor in the McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering at the University of Texas at Austin. A novel model of 14 million homes in California built with advanced machine learning will allow researchers to understand how much smoke entered homes and where.

A key goal of all these efforts is to share evidence-based, rapid answers to the affected communities. In addition, the findings will be shared with civilians, firefighters, businesses, researchers, and government agencies.

The Spiegel Family Fund, which is funding the study, was founded by Evan Spiegel, the co-founder and chief executive officer of Snap, Inc. He grew up in Pacific Palisades, a town devastated by the recent fires, and still lives in Los Angeles with his family. In an emotional love letter to the city as the fires raged, he wrote: “We are not the first community to face a megafire. We will not be the last. But we will use our strength, our ingenuity, and our love to create again and anew.”

By funding the research study, Spiegel said he hoped to help spur that recovery and learn critical insights that could protect health and well-being both in Los Angeles and in other cities affected by wildfires in the future.

Other researchers on the team include Joe Allen, Francesca Dominici, Amruta Nori-Sarma, and Mary Rice from Harvard Chan School; Dave Allen, and Pawel Misztal from UT Austin; and David Eisenman, Katie McNamara, and Yifang Zhu from UCLA Fielding.

Last Updated

Featured in this article

Leading the fight to end homelessness

With continued support from Diana Barrett, MBA ’74, DBA ’79, a first-of-its-kind initiative at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health is working across disciplines and sectors to develop lasting solutions to America’s homelessness crisis

Diana Barrett, MBA ’74, DBA ’79, believes that creating a society where each person can reach their full potential starts with ensuring universal access to secure housing.

Homelessness in the United States has grown into a national crisis, affecting over 650,000 people on any given night. A severe shortage of affordable housing, combined with multiple social system failures, makes the problem hard to address. For those experiencing homelessness, the health impacts are staggering: their life expectancy is decades shorter than the general population, and up to three-quarters struggle with mental health and substance use disorders.

“There’s no great mystery,” Barrett says. “We don’t take care of people, and then we wonder why they’re not doing well.”

In 2019, Barrett made a gift to help launch the Initiative on Health and Homelessness (IHH) at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, providing additional support in 2022. From the start, she recognized the initiative’s potential to improve understanding of the pathways into and dynamics of homelessness, incorporate this knowledge into Harvard’s curricula to train future leaders, and unite experts across all sectors to influence policy and create a coordinated system of care and prevention. Her most recent gift in 2024 will expand research, education, and outreach efforts, advancing IHH’s goal of becoming a leading center in the national effort to end homelessness.

“The initiative simply wouldn’t exist without Diana’s support,” says Howard Koh, Harvey V. Fineberg Professor of the Practice of Public Health Leadership at Harvard Chan School and inaugural faculty chair for IHH. “Diana inspires us to aim higher and push harder to address one of the most glaring health inequities of our time. Right now, with her constant encouragement, we’re assembling an advisory group and intensifying our strategic planning. It’s challenging work, but we’re making progress, and we are all so proud of that.”

As IHH enters this next stage in its development, it builds on a strong foundation. To date, IHH has established a trusted national platform that connects a growing community of academic expertise and practice through regular events and collaborations. It also fosters and supports students to become leaders in the field through research opportunities, mentorship, and a new course on homelessness and health.

Changing the Narrative

As a board member of the Lord’s Place, a Florida-based organization focused on breaking the cycle of homelessness, Barrett has seen firsthand how quickly a life can unravel.

“Anyone could become homeless,” she says. “A car breaks down, you lose your job, and suddenly you’re facing eviction. But with the right support at the right time, homelessness is often preventable.”

Yet she finds that common misconceptions persist. “Every time I talk about my work on homelessness, people say, ‘Oh, they all have mental health problems, or they all struggle with substance abuse—it’s unsolvable, intractable.’ But that’s simply not true.”

After 25 years at Harvard, where she taught business and public health, Barrett left academia in 2005 to start the Fledgling Fund, a foundation dedicated to supporting films and other creative media projects that educate, engage, and mobilize people around complex social issues. She hopes IHH will shift public perceptions of homelessness through the power of storytelling.

“We live in a visual world, and storytelling is incredibly powerful,” she says. “If you see the challenges in cities like San Francisco—the image of tents lining the streets stays seared in your memory. No article alone can convey that.”

A Novel Solution to a Complex Problem

Research and education on health and homelessness in the U.S. have been critically underfunded and overlooked, leaving the academic community unable to fully investigate the root causes, health impacts, and possible solutions. As a result, people working to tackle this urgent health equity issue lack the robust evidence needed to develop effective systems, policies, and interventions.

As the first program of its kind within a school of public health, and one of only a few such academic hubs nationwide, IHH has made significant strides over the past five years. It launched Harvard’s first course dedicated to homelessness, covering essential topics such as demographic trends, the effect of structural racism, and the unique challenges faced by specific groups, including veterans and families.

“When students come to the University from around the world, they shouldn’t walk through Harvard Square and view people lying on the street as something normal,” says Koh. “At the very least, students should leave our School and University with a deeper understanding of the societal forces that put people there—and with insights into the policy solutions that could address and prevent homelessness.”

The initiative has become a draw for incoming graduate students, who cite it as a deciding factor in choosing Harvard for their studies. “Now, it’s possible for someone to build an academic career studying homelessness—a path that simply didn’t exist five years ago,” Barrett shares.

Through a monthly seminar series of research and practice, IHH convenes scholars and advocates to explore the complex intersections of health and homelessness. The initiative also leverages partnerships across the University—working with faculty in the health sciences, urban design, policy, law, and business—to promote a powerful interdisciplinary approach, including collaborations with the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, the Harvard Kennedy School Government Performance Lab, and the Harvard Advanced Leadership Initiative.

“No one group or individual can solve this,” Koh says. “It must be a committed interdisciplinary response.”

The initiative has hosted several national summits to identify effective solutions, engage political leaders from mayors’ offices, and build an expanding network of external stakeholders, including the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness; the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program; state and local leaders in Massachusetts, California, Oregon, New York, Texas, and Illinois; and national nonprofits.

Barrett envisions IHH as a leading authority on health and homelessness. “I’d like Harvard to be so good at what we do that if someone asks, ‘What’s happening with homelessness right now in Atlanta?’ the answer would be, ‘Call Harvard. Call IHH. They’ll know.’ ”

Last Updated

Featured in this article

Boosting community partnerships for immigrant mental health

At a time of heightened uncertainty for immigrants in the U.S., two efforts at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health are focused on strengthening access to community mental health resources.

Both efforts involve connections with the Malden, Mass.-based Leah Zallman Center (LZC) for Immigrant Health Research, which works with partners—such as local immigrant communities, advocates, policymakers, and funders—to produce research aimed at spurring improvements in immigrant health and well-being.

Over the summer, health management student Jennifer Zhang, MPH ’25, did a practicum at the center and produced a policy brief on immigrant mental health that was finalized in November. The brief, created with colleagues at the LZC, summarized structural inequities impacting mental health among immigrants and proposed solutions.

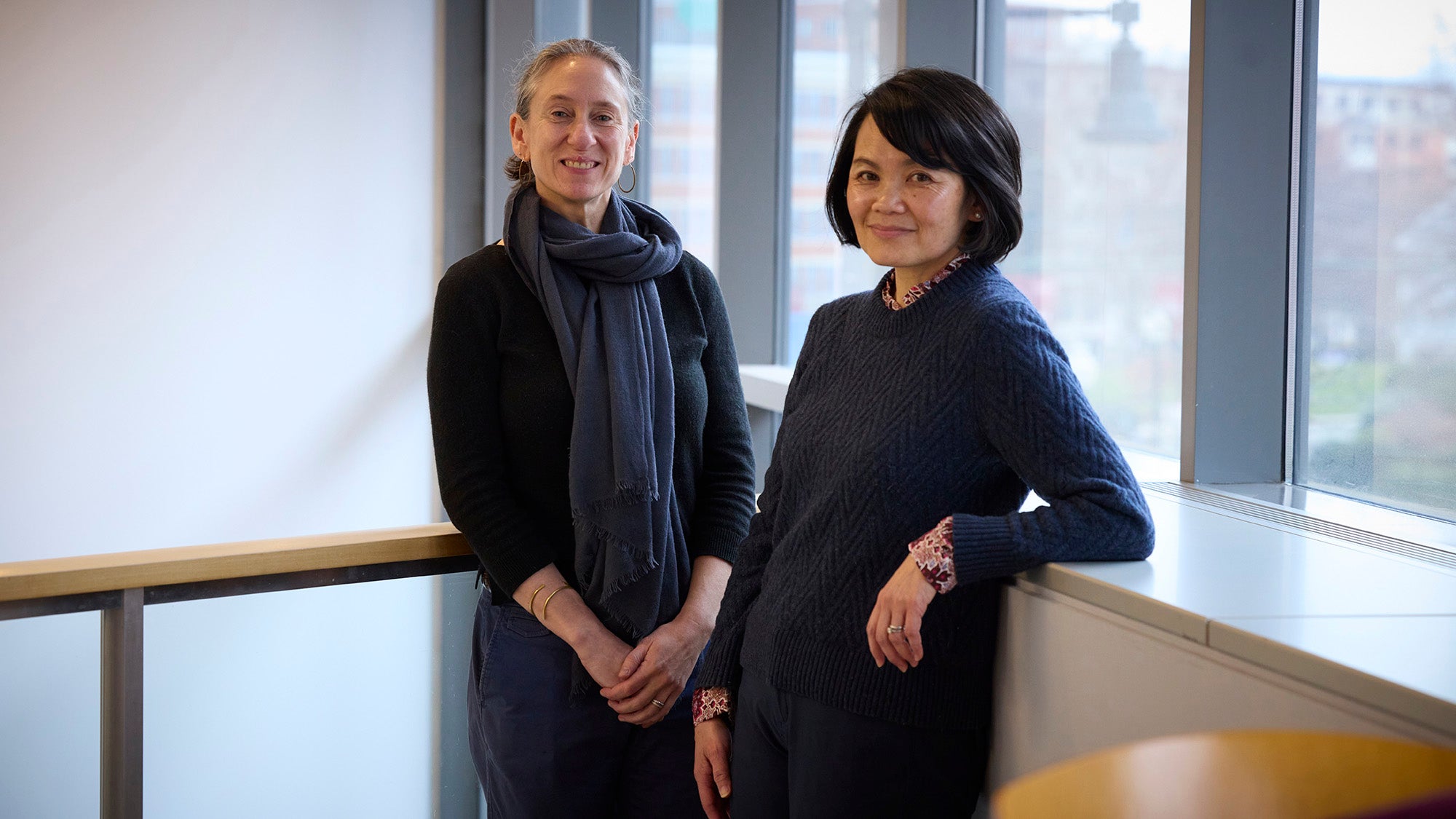

Separately, a new collaboration between Harvard Chan School and LZC will address immigrant mental health and well-being through research, education, and partnerships with local groups. The work with the LZC—part of a new Harvard Chan initiative called Partnerships for Community Health and Immigrant Well-being—is being led by Maggie Sullivan, instructor and health and human rights fellow at the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, and Jocelyn Chu, director of community engaged learning at Harvard Chan School, in partnership with the LZC.

Varied experiences, varying needs

The brief produced by Zhang and LZC colleagues outlined some of the life experiences unique to immigrants that pose risk factors for mental health, including trauma as a cause or result of migration, lack of access to health care services and insurance, lack of legal status, living in multigenerational households, and cultural and language barriers. Given these factors, it’s important to create tailored, trauma-informed, and culturally effective mental health services and policies to address immigrants’ unmet needs.

To address barriers to mental health treatment access for immigrants, the authors offered a number of solutions, such as expanding immigrants’ insurance eligibility and diversifying the mental health workforce to help overcome language and cultural barriers.

Zhang said that her biggest takeaway from working on the brief is that different immigrants have different needs. “You can’t lump immigrants into one bucket, because their experiences are varied,” she said. For example, childhood “language brokering”—referring to when children serve as translators for their parents because they’ve picked the language more quickly—has been linked with both negative and positive impacts on children’s well-being. In some cultures, language brokering can lead to depression and anxiety; in others, it doesn’t, because they feel proud to perform a valuable service for their family.

“Things that I saw as universal risk factors were, after all, not universal risk factors,” Zhang said. “That is a really important lesson and illustrates why we need tailored mental health services that are culturally responsive.”

Learning, partnering, teaching

Under the Partnerships for Community Mental Health and Immigrant Well-being initiative, Harvard Chan students and faculty will partner with the LZC to assess the landscape of community mental health resources available to marginalized immigrants in the greater Boston area and increase opportunities for public health students and faculty to be involved in community-based mental health research and practice. Practicum placements for Harvard Chan students at the LZC are already being planned for next summer.

“One of the things we’re thinking about is how we, as an educational institution, can be better stewards of community mental health in places in close proximity to the School—like Mission Hill, Dorchester, Mattapan, Chelsea, or East Boston—whether through student practicums, course development, or helping to grow mental health services that already exist in these communities,” said Sullivan.

She pointed out that a typical model of mental health care delivery may involve a therapist meeting with a patient, but that model may not line up with what immigrants need. “You can ask if a patient wants individual therapy, but that may not make sense if the person is most worried about the difficulty making rent to live in a densely crowded shared room,” she said. “They may say, ‘I don’t know how therapy is going to help me with this. I just need help with finding work and paying rent.’”

Beyond financial support for things like rent or food, immigrants may also benefit from group interventions such as yoga or art classes or mindfulness-based stress reduction training. Chu hopes that, in the future, information about these sorts of community mental health approaches can be incorporated into courses at Harvard Chan School.

A welcome partnership

Jessica Santos, LZC director, praised the contributions that Zhang made during her practicum. “She brought her own ideas and experiences to her summer work, and really contributed another dimension to the research we’d been looking at on mental health in immigrant communities,” Santos said.

She added that the partnership with the School comes at a critical time. “The next couple of years for immigrants will be very chaotic and insecure,” she said. Given the political landscape, she is heartened to be working with Chu and Sullivan. “They embody the type of work we do at the Zallman Center, with one foot on the ground, one foot in research—scholar-activism type work,” she said. “It’s exciting that Harvard Chan School is supporting that type of research.”

Last Updated

Featured in this article

Building a Strong and Healthy LGBTQ Community

A gift from Mike Dillon MPH ’23 is helping to advance work on LGBTQ health equity at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

For Mike Dillon MPH ’23, there has never been a more crucial moment to address the public health crisis facing LGBTQ communities.

LGBTQ individuals encounter significant challenges in accessing equitable and inclusive health care. Faced with discrimination, stigma, limited access to care—including gender-affirming care and reproductive care—and high rates of violence and disinformation directed at them and their health care providers, LGBTQ individuals experience alarming health disparities. This includes higher incidences of mental health conditions, substance use disorders, homelessness, sexually transmitted infections, and HIV/AIDS. They are less likely to have health insurance and often delay care, and many experience a lack of cultural competence from providers.

Galvanized by the urgent need for improved health care delivery and outcomes for LGBTQ communities, Dillon has made a gift to support efforts to advance LGBTQ health equity at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The funding will help equip emerging public health care practitioners with essential knowledge and resources.

The gift aims to establish scholarships to attract talented students interested in LGBTQ health equity and create research grants that will support the work of graduate students and postdoctoral fellows. In addition, the gift will support University-wide service fellowships so that emerging leaders from across Harvard’s Schools can apply to an internship or practicum in the field.

Dillon hopes to see more interdisciplinary collaboration at Harvard around these issues and for researchers to coalesce around the intersectionality of marginalized communities.

“Public health is how we change history,” he says. “You only have a strong community if you have a healthy community.”

Making an Impact at Harvard and Beyond

After a successful 30-year career in various leadership roles at PricewaterhouseCoopers, Dillon sought a new way of making a difference outside of the corporate world.

He enrolled in the Harvard Advanced Leadership Initiative (ALI), a one-year, University-wide educational program for experienced leaders to address some of society’s most intractable challenges through interdisciplinary learning, leadership development training, and peer collaboration.

“ALI teaches you to think about your pathway to making social change and how you can make maximum impact,” says Dillon. “It gave me the freedom to think outside the box about what my legacy could be and how I could work toward change.”

After completing his fellowship, he was inspired to pursue a master’s degree in health policy at Harvard Chan School. “I kept coming back to LGBTQ health equity,” he says. “I knew it was important for me to learn the language of public health.”

Dillon wanted to do more to support the burgeoning research and scholarship in this field, which led him to make a gift to Harvard.

Brittany Charlton SM ’11, ScD ’14, associate professor of epidemiology at Harvard Chan School, is thrilled that students will now have the opportunity to address how discrimination impacts LGBTQ people.

“Mike Dillon’s gift is transformative in helping us make a meaningful and lasting impact for LGBTQ health equity,” says Charlton, who is also associate professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, co-director of the Harvard SOGIE (Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity and Expression) Health Equity Research Collaborative, and founder of the Harvard Sexual and Gender Minority Health Mentoring Program.

“LGBTQ people have become the target of an utterly unprecedented wave of policies across the U.S.—including those that limit access to health care and criminalize teachers for discussing the existence of LGBTQ people,” she says. “One in ten people in the U.S. identify as LGBTQ, and this population will grow as that number is twice as high among young people. It’s essential that we educate our learners so that they create the necessary evidence base through research and share this work to inform policy.”

Remembering the Past to Create a Brighter Future

A longtime leader, volunteer, and board member with LGBTQ health equity organizations, including the Trevor Project and the San Francisco AIDS Foundation Project, Dillon has witnessed firsthand how public health research benefits LGBTQ youth. He also remembers the fear of growing up during the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the crucial activism and public health messaging that opened many doors for LGBTQ rights.

“We are now at risk of losing rights that were hard won by many individuals and organizations years ago,” he says. “We thought the battle was over, but we’re still fighting.”

Charlton, reflecting on her 20 years of public health work in LGBTQ communities, has seen the field transform from a primary focus on HIV/AIDS to one that encompasses the diversity of LGBTQ communities impacted by a range of health inequities.

“It is profoundly meaningful to me as a queer woman to help build a diverse, inclusive, and equitable home for LGBTQ health work,” she says. “We must prepare the next generation of leaders—not only to document that inequities exist, but also to design interventions and advocate for policy changes that tangibly improve the lives of LGBTQ people.”

With more opportunities at Harvard for students to access fellowships, internships, and practicums, as well as engage in research, Dillon hopes that the University can attract practitioners early in their careers. He sees vast possibilities for students, who could go on after graduation to pursue meaningful work across sectors ranging from public health to legal advocacy to app development.

“We have incredible students who are part of this community,” he says. “This is the right place to do this work, and the time is now.”

A Study in Health Disparities

A 2024 study from Harvard Chan School and collaborating institutions found that women who identify as bisexual or lesbian experience higher rates of premature death compared to heterosexual women.

Led by Charlton and postdoctoral research fellow Sarah McKetta AB ’09, SM ’12, the study underscores the critical need to address sexual orientation–related health inequities. As the study notes, bisexual and lesbian women experience stigma and discrimination that often result in chronic stress and unhealthy coping mechanisms, which can lead to premature mortality.

In addition to this new research, Charlton is also the founding director of the recently launched LGBTQ Health Center of Excellence, a partnership between Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute.

Under Charlton’s leadership, the center aims to mitigate such adverse outcomes and advance health equity by focusing on several areas:

- Training to prepare the next generation of LGBTQ health leaders

- Research to expand the evidence base of LGBTQ health

- Dissemination to inform policymakers, health care providers, and the larger public about how to improve LGBTQ health most effectively

Last Updated

Featured in this article

Can optimism and kindness contribute to worker health and well-being?

Hayami Koga, MPH ’16, PhD ’23, is exploring how a Japanese philosophy of hospitality and mindfulness can help workplaces become more psychologically healthy environments.

May 31, 2024 — Hayami Koga remembers her father always telling people to “laugh for their health.” It wasn’t until she was in medical school that Koga realized the wisdom in that advice. In Japan, where Koga is from, sudden deaths from overwork became such a common occurrence that a word was coined in the 1970s to describe them: karoshi. Through her work as a physician and public health researcher, Koga is hoping to nudge workplaces in Japan and elsewhere in a healthier direction.

“I have seen how work can be dangerous, toxic, and unhealthy,” Koga said. “I want to change the structure of work from something that is harmful to something beneficial to health, a source of your well-being, something to be optimistic about.”

Koga attended medical school at the University of Occupational and Environmental Health in Japan, an institution with a focus on worker health. But she came to believe that its approach—which emphasized educating patients about preventing and managing health risk factors like high cholesterol and hypertension—didn’t go far enough toward getting at the root causes of poor physical and psychological health in the workplace.

She continued to explore her interest in worker health and well-being after graduation, reading avidly while working first as a doctor at a hospital, and later as a research analyst with Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. One book she came across was Social Epidemiology, edited by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health professors Lisa Berkman, Ichiro Kawachi, and Maria Glymour, and it changed the trajectory of her career, inspiring her to apply to the School.

“The book looked at health with a more structural and population-based lens and focused on social determinants,” Koga said. “None of this was part of my medical school curriculum, so it was very new to me, but I wanted to do whatever I could to understand it.”

Health benefits of optimism

Koga earned an MPH in social and behavioral sciences in 2016, and a PhD from the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin School of Arts and Sciences in 2023, for which she studied in the Population Health Sciences program in partnership with Harvard Chan School. Two years ago, she was lead author on a study that linked higher optimism with longer lifespan and a greater likelihood of living past age 90 for women across racial and ethnic groups, which was covered by a number or media outlets. She passionately believes that increasing optimism can be beneficial to everyone’s health and hopes the work in this space continues.

Koga’s doctoral studies were supported by financial aid from the Dillon Family Fellowship. The fellowship gave her the opportunity to join the Work and Well-being Initiative, a research partnership between Harvard Chan School and MIT Sloan School of Management that seeks to provide a deeper understanding of work conditions that support worker well-being and to identify policies and practices that enable workers to be healthy in and outside of the workplace.

“As the oldest member of the Dillon family, and a long-time advocate for the work being done through Harvard Chan School, I am delighted that our fellowship inspired Hayami to continue her optimism research,” said Phyllis Collins. “Optimism, and ways to obtain and sustain it, is very important to me—especially in workplaces where we spend so much of our time. Here’s to hoping we can bring an end to karoshi.”

Sharing omotenashi

As a postdoc, Koga is continuing to explore how promoting positive psychological factors in the workplace can improve worker health and well-being. She’s supported by Plan Do See, a hospitality group with a mission to share omotenashi—a Japanese philosophy of hospitality and mindfulness—with the world. “I would translate omotenashi to more Western terms by saying it’s something like acts of kindness, which I think contributes to worker well-being. Part of my research is focused on why that is,” Koga said.

Seiko Miyama, an executive assistant at Plan Do See, said that employee well-being is one of the company’s top priorities. “We were very excited to bring Hayami on board to help us continue creating outstanding work environments and to elevate our outcomes. When we met her, we were instantly drawn to how well her research and interests aligned with our values at Plan Do See, so we’re thrilled to team up with her to share omotenashi with the world.”

Koga’s advisor Laura Kubzansky, professor of social and behavioral sciences, appreciates what can come from students following their curiosity. “The intellectual capital students and researchers, like Hayami, bring is incredibly special and heartening. They are passionate and committed and looking to make the world a better place by answering their own questions.”

To help answer questions about well-being as part of their work together, Koga and Kubzansky considered early psychological research on optimism conducted by Martin Seligman who coined the term “learned optimism.” While studying his work, Koga coincidently came across a reference to Seligman’s research on optimism and health in a book her father had published about personal development and success. Kubzansky shares a similar family connection: She and her father, who she calls “the ultimate optimist,” were able to publish a paper about optimism together before he died.

Koga calls Kubzansky and Harvard Chan School’s Lisa Berkman—another mentor—“super women.” She said, “They have overcome a lot to be where they are and have taught me that being female is not a setback. It was hard to imagine myself in this field alongside people like them. It is rare for a Japanese physician, especially a woman, to pursue a PhD in the U.S.—and I did it while raising a kid! I am proud of that and what I have accomplished—and I could not have done it without these role models.”

In 2023, Berkman, who is co-editor of the book that inspired Koga to apply to Harvard Chan School, hosted her graduation dinner. Koga said, “Full-circle stories like this are so special to me and make me hopeful for what we can all achieve together in this field.”

Photo: Kent Dayton