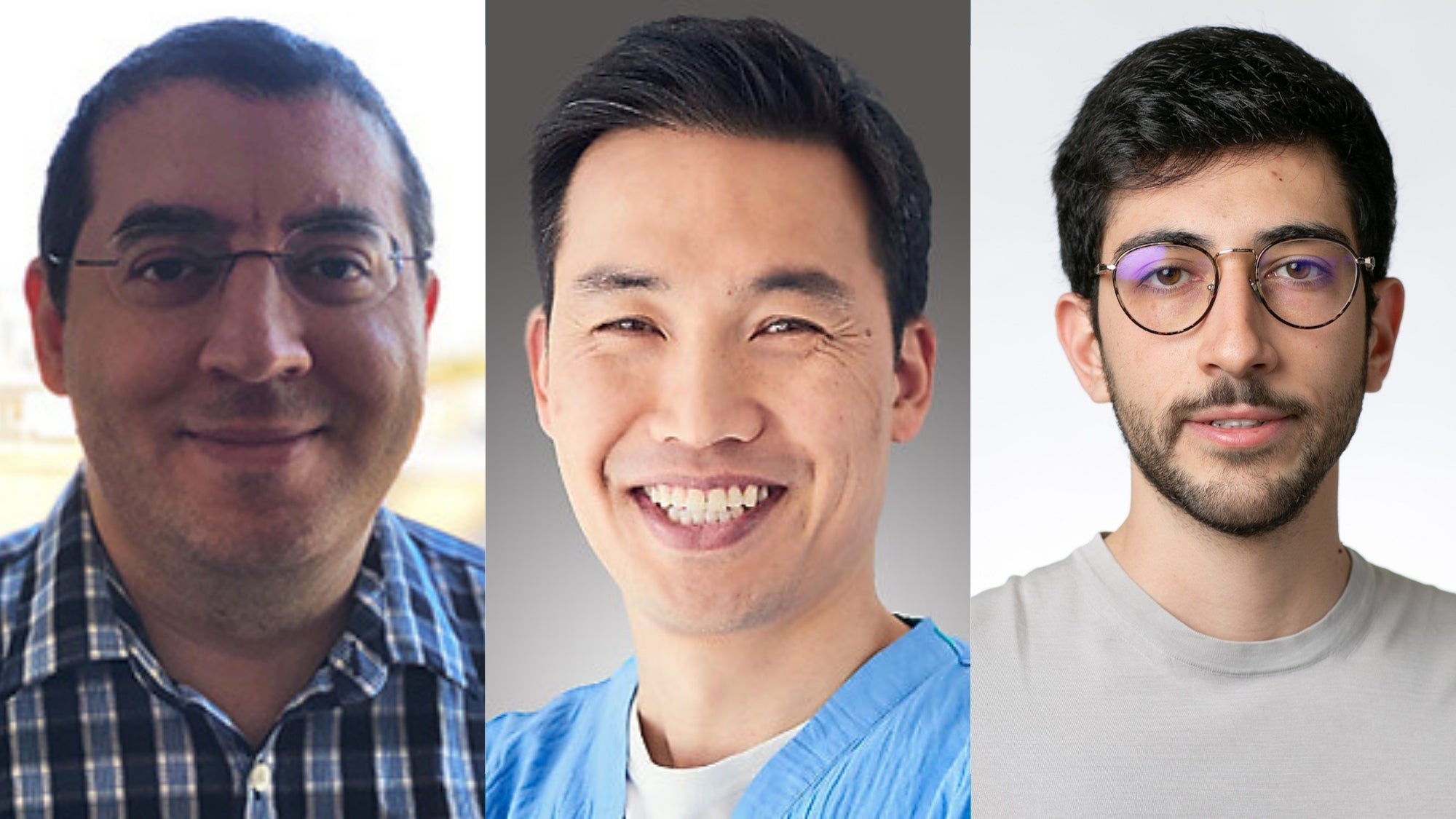

Q&A with Konrad Stopsack

Konrad Stopsack, an adjunct professor in the Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, on January 1, 2025 took over as head of the Department of Epidemiological Methods and Etiological Research at the Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology – BIPS. Stopsack is an epidemiologist focusing on molecular and cancer epidemiology with a background as a board-certified internal medicine physician. His applied research combines well-defined observational studies and state-of-the-art genomics for research on cancer and cancer precursors. His methodologic and teaching interests include application and further development of epidemiologic methods to improve reproducibility, interpretability, and efficiency of epidemiologic studies. In this Q&A, learn about the new work that he’s doing, how his career trajectory led from Harvard to BIPS, and what the future may hold.

Can you tell us about your new role as Chair in the Department of Epidemiologic Methods and Etiologic Research, Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology – BIPS in Bremen, Germany?

Epidemiology is a relatively young discipline in Germany that has grown remarkably in recent years. BIPS is the largest institute focused on epidemiology and prevention in the country today. Across the institute, we do etiologic epidemiology, asking what makes people sick and what keeps them healthy? We then model interventions, asking what if we intervened on a causal factor? And we do implementation research, asking how well do interventions work in real life? My department focuses on the first question. We run prospective cohort studies, such as IDEFICS/I.Family cohort of initially children, now young adults, across eight European countries, and the Bremen study center of the Germany-wide NAKO cohort. Faculty in my department work on nutritional epidemiology and in molecular epidemiology, with our own biobank. What drew me to BIPS were not only the leadership role with an opportunity to shape how epidemiology research will look like in the future, but particularly the collaborative spirit and deep methodological expertise at the institute.

How has your time at Harvard prepared you for this role?

I initially came to the Harvard Chan School as a masters student, thinking I would learn how to better make use of numbers in medicine, which is something that I had sorely missed in medical school. I did learn those “numbers,” taking lots of biostatistics courses. Yet what left a deeper impression was the first of epidemiology courses, EPI500 taught by Albert Hofman. He introduced us to the different study designs that gave rise to those numbers. After my internal medicine residency training, when I made the tough decision to become a full-time researcher, I did a postdoc at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York in cancer epidemiology and was back at the Harvard Chan School for methods coursework and research. I credit Murray Mittleman with his EPI247 course for opening my eyes how exciting epidemiologic methods are once one dares to read the original papers. And in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, I learned what it takes to put data collection and analytical methods into practice.

What are some current research questions you’re excited to be working on?

I find it remarkable how little we know about what causes prostate cancer, or at least how few risk factors we can all agree on. One could diagnose prostate cancer over the life course of about every fifth person on this planet! Lorelei Mucci and Ed Giovannucci have laid a lot of the foundations in this area of epidemiology. I hope to continue my NIH-funded project that looks at prostate cancer as a number of molecularly different diseases that perhaps need different prevention strategies each. I am also intrigued by early molecular changes measurable in our bodies with technologies like deep sequencing that are precursors to cancer and cardiovascular disease. Some of these changes are detectable quite early in life. I hope we can learn more from them on how to prevent initiation of disease precursors. Overall, I am just very interested in considering multiple and sometimes opposing health effects of modifiable risk factors, which is perhaps not surprising with my background in internal medicine and the exposure-focused approach that BIPS takes.

In your upcoming April 30th seminar with us, you will touch upon leveraging data science as a means to conducting epidemiologic analyses in a more fun and efficient way. Can you elaborate on that? What can we look forward to in your talk?

When we as a field talk about epidemiologic methods, we often focus on a statistical model as the main step to getting “the” result. In my seminar, I will try to widen that perspective on epidemiologic methods a little. How do we develop and communicate our research plans in a team? How do the numbers from a regression model make it into a table in a manuscript? I will show some simple data science approaches and free software that are quite useful to speed up our work in the hybrid work environment that we have today. I will argue that such approaches have profound implications for the reproducibility of our study results. And for how we educate our students and trainees. Perhaps even descriptive epidemiology could be in a better shape once we become more comfortable in how to show actual data in our papers, not just modeling results. There is reason for hope – the GitHub organization for Harvard Chan School Epidemiology already has over 100 students, postdocs, and faculty as members.

What do you hope to do in the near future? Are there opportunities for researchers here to collaborate with you across the Atlantic?

One of my main goals is indeed to strengthen ties across the Atlantic. In epidemiology, just as elsewhere in science, we are simply stronger together. We are setting up programs for trainees and faculty to come to BIPS, but anyone potentially interested should simply feel free to reach out.