Although many are aware of air pollution’s link to respiratory diseases, its impact on the cardiovascular system is less well-known. Here, Harvard Chan environmental health experts explain how air pollution affects the heart, what components of air pollution are most dangerous, and steps people can take to protect themselves.

Air pollution has been linked with a long list of serious health outcomes. In slide presentations, Francine Laden uses a graphic illustration that shows the wide range of damage that has been linked to pollutants. The graphic features an outline of a human body. Over a series of slides, the body becomes covered with about two dozen word bubbles referencing studies that have found links between air pollution and conditions ranging from lung cancer to cognitive decline to infertility. It has also been linked with premature death.

“And those are all the outcomes that just [Harvard researchers] have looked at,” said Laden, professor of environmental epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “It’s just overwhelming in terms of all the different associations that you can find with air pollution.”

Cardiovascular health risks sit atop that hefty list, Laden and other Harvard Chan experts agree. Yet while people intuitively make the connection between air pollution and lung damage, the connection with its impact on heart health—for which there is “incontrovertible evidence,” according to Kari Nadeau, John Rock Professor of Climate and Population Studies and chair of the Department of Environmental Health—may not be top of mind.

“From my perspective, while people are increasingly understanding that air pollution affects the cardiovascular system, not enough really get it,” said Nadeau, an allergy and asthma specialist who works with children and adults. “My typical patient doesn’t see the connection automatically. I have to explain it to them, and then they understand it.” Added Mary Rice, Mark and Catherine Winkler Associate Professor of Environmental Respiratory Health, director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment, and a pulmonologist who sees many patients with both chronic lung disease and heart disease, “I don’t think most people realize just how harmful air pollution is to our health, because it is mostly invisible.”

Doug Dockery, John L. Loeb and Frances Lehman Loeb Professor of Environmental Epidemiology, Emeritus, led the landmark 1993 Harvard Six Cities Study that revealed a strong link between air pollution and mortality risk. Referring to the risks posed by air pollution to heart health, he said, “It is a big issue. We’re talking about millions of people affected.”

Dockery cited a 2017 Lancet study that quantified the global burden of disease and death related to fine particulate matter, or PM2.5—the most damaging component of air pollution. This type of pollution was responsible for some 4.2 million deaths globally in 2015, the study found. Of those deaths, 2.4 million were cardiovascular-related, far outpacing deaths from either chronic obstructive lung disease (863,000 deaths) or lung cancer deaths (283,300).

Mounting evidence

Since the publication of the Six Cities Study, Harvard Chan School researchers have been at the forefront of much of the research on the connection between air pollution and cardiovascular impacts, co-authoring hundreds of papers on the topic—and the work continues. “It’s one thing that I’m very proud of,” noted Dockery, who formerly chaired the Department of Environmental Health. “We took the lead in this and were really instrumental in showing these associations.”

The Six Cities Study played an early and crucial role in uncovering just how dangerous air pollution was, showing that its effects on mortality risk were much greater than had been observed in previous studies. The study generated years of criticism and questions about its quality. But numerous follow-up studies confirmed the findings, and ultimately the study helped pave the way for strengthened air quality standards in the U.S. and beyond.

Dockery admits that, when he was working on the Six Cities Study, he initially assumed that any link found between air pollution mortality risk would be because of respiratory disease—not cardiovascular disease (CVD). “We weren’t thinking about air pollution as a risk factor for CVD at that time,” he said. “In fact, the original hypothesis of the Six Cities Study was that respirable particles would accelerate the development of and ultimately death from chronic obstructive lung disease.”

But the results showed otherwise. “We found a very strong association with CVD deaths, but not with respiratory deaths,” Dockery said. “We thought it must be a coding error—we thought that respiratory deaths had been miscoded as CVD deaths.”

Over time, the connection between air pollution and CVD has become increasingly clear. Studies from Harvard Chan experts and others have shed light on a raft of cardiovascular harms associated with both long- and short-term air pollution exposures, including links with heart attack, stroke, and premature death and risk factors such as high blood pressure, heart rhythm and heart rate changes, and inflammation.

Dockery recalled a paper that showed one of the serious short-term effects of air pollution—a 2001 study led by Annette Peters, who was doing a postdoctoral stint with him at the time. The study looked at patients with myocardial infarction (MI)—heart attacks—in the Boston area between January 1995 and May 1996. The researchers, including Dockery and Harvard Chan colleagues James Muller and Murray Mittleman, found that the risk of MI onset was higher if PM2.5 levels had been elevated in the previous two hours.

Joel Schwartz, professor of environmental epidemiology, has also conducted pivotal research showing how air pollution affects CVD and other conditions. As early as 1994, he was publishing research showing that particles were associated with increased hospital admissions for heart disease among Medicare recipients. He and colleagues have studied air pollution-related deaths that take into account both location and time. For example, a 2013 study, led by Jaime Madrigano—a doctoral student at the time of the study and now an associate professor at Johns Hopkins— found that long-term exposure to PM2.5 was linked with increased odds of having a heart attack. A 2017 study examined the entire Medicare population and found that PM2.5 exposure increased the risk of death. More recently, a 2024 study led by Yaguang Wei, formerly an associate in the Department of Environmental Health and now an assistant professor at Mount Sinai, found that chronic exposure to fine particulate pollution may increase seniors’ risk of hospitalization for a variety of cardiovascular conditions, particularly ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure, and arrhythmia.

Additional studies by Schwartz and colleagues have used causal modeling methods—epidemiological and statistical methods that help determine causation—to strengthen the link between air pollution and cardiovascular problems. For example, a September 2023 study used causal models to analyze four million hospital admissions for heart attack in the U.S. Medicare population from 2000 to 2016, finding that as the amount of PM2.5 in the air increased, so did admissions. The risks were elevated even at PM2.5 levels below EPA limits.

Much of Laden’s air pollution research has used data from the Nurses’ Health Studies. One significant study, a 2015 analysis led by Jaime Hart, associate professor in the Department of Environmental Health, teased out which groups were most susceptible to particulate matter-related CVD risks. Women with diabetes faced the highest risks compared to those without the disease. Other groups—including older women, those with obesity, and those living in the Northeast and the South—also faced elevated risks.

Some of Laden’s work has focused on factors that might mitigate air pollution’s CVD harms. A 2021 study, for instance, found that PM2.5’s harmful effects were lessened in areas with more trees, grass, and other vegetation.

Other studies from Harvard Chan researchers have delved into the mechanisms involved in the link between air pollution and CVD. In Nadeau’s lab, researchers are working to identify and characterize biomarkers of acute and chronic exposure to air pollution that predict cardiopulmonary diseases. Better understanding of the biology behind air pollution’s harms will ultimately help guide the development of treatments, Nadeau said.

As with many other environmental exposures, particulate pollution affects some groups more than others. Those most at risk for cardiovascular impacts include people with pre-existing lung or heart disease, diabetes, or other chronic conditions; those with social and economic disadvantages; and elderly people, pregnant women, and children.

Tiny, deadly particles

The smaller the particles in air pollution, the worse they are for cardiovascular health, evidence shows. PM2.5 particles are considered the most dangerous.

The burning of fossil fuels from coal plants, steel mills, cars, and trucks are the primary source of dangerous PM2.5. They are also a component of wildfires. Harvard Chan researchers have begun to look at these sources to see which produce the most dangerous PM2.5. A 2023 study co-authored by Francesca Dominici, Clarence James Gamble Professor of Biostatistics, Population, and Data Science, for instance, found that coal plant-generated PM2.5 may be twice as deadly as PM2.5 from other sources.

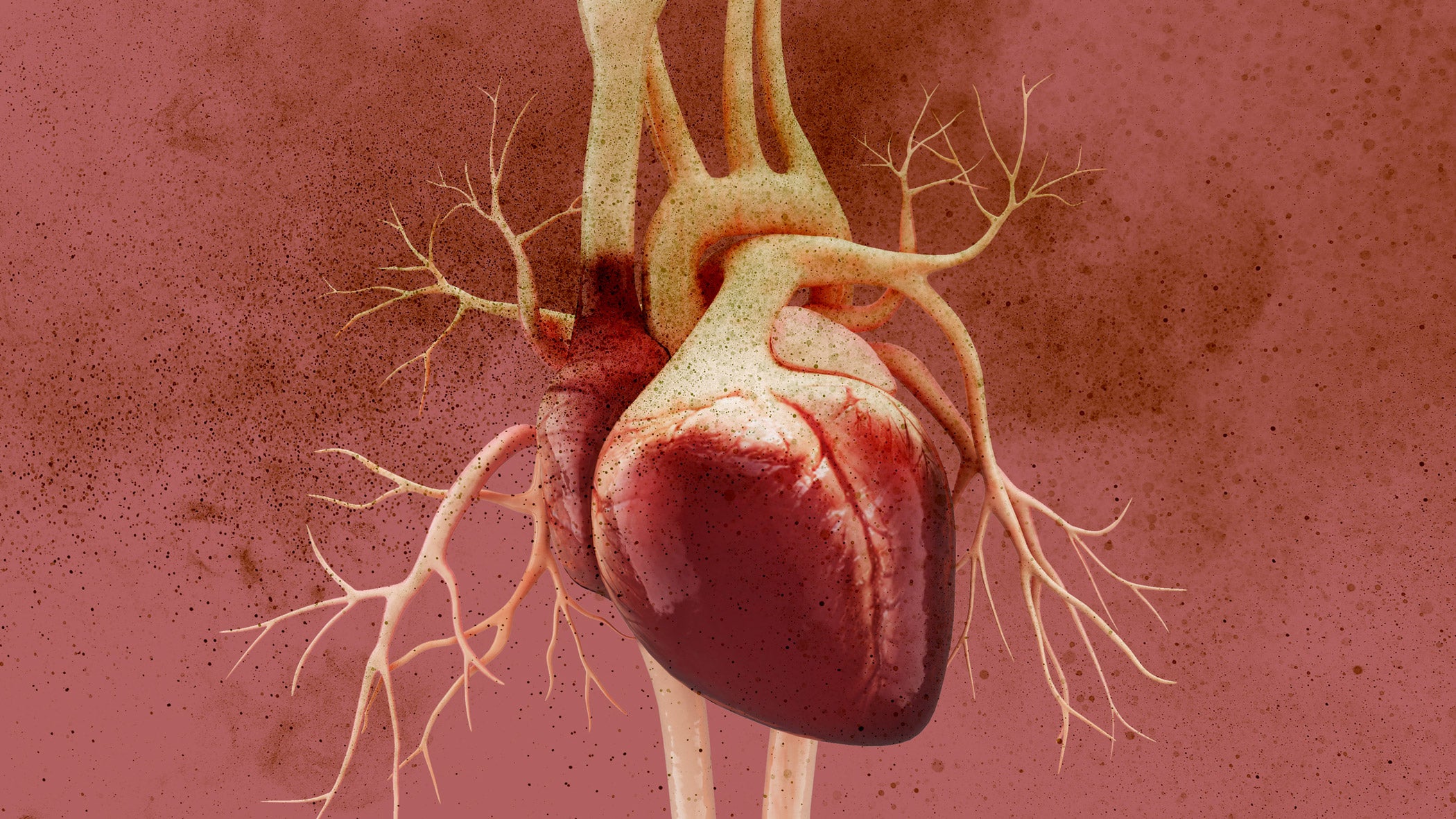

The reason that PM2.5 particles can create cardiovascular havoc is precisely because they are so tiny. “The tiny particles can get into your capillaries and into your bloodstream. What’s the first organ that picks up these particles from the bloodstream? The heart,” said Nadeau.

There are several ways that the particles interfere with the cardiovascular system, Schwartz noted. Some simply move through the super-thin wall that separates the alveoli—the tiny air sacs in the lungs—and the capillaries. Others dissolve in the fluid that lines the inside of the lungs and can pass through lung tissue into the blood. Others may enter the brain via the olfactory nerve, potentially triggering systemic inflammation that can impact cardiovascular functions. Particles can also trigger nerve receptors in the lungs and send signals that can affect the electrical control of the heart.

Protection and prevention

There are steps people can take to protect their cardiovascular health from harmful particulates, according to Rice and Joseph Allen, associate professor of exposure assessment science and director of the Healthy Buildings program. They can monitor air quality in their neighborhood using the Environmental Protection Agency’s airnow.gov website; wear an N95 mask if the outdoor air quality is poor; and, if possible, use a HEPA air purifier to remove particulate pollution that seeps into their homes from outdoors. Allen said to be sure air purifiers are the right size for the room where they’re placed. “My rule-of-thumb is to find an air cleaner with a clean air delivery rate (CADR) of 300 for every 500 square feet of space,” he said, noting that manufacturers typically report CADR on a product’s box or on their website. Rice noted that if you can’t afford an air purifier, you can make your own. For people with central HVAC systems, Allen recommended upgrading to a MERV13 filter or higher.

On the research front, Rice is studying the effectiveness of air purifiers in protecting respiratory and cardiovascular health. She is conducting a randomized controlled trial comparing health outcomes among two groups of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD)—one group that uses air purifiers and one that doesn’t—over the course of one year.

Not everyone has access to air purifiers and HVAC filters, of course. “We can wear masks and have filters, but these small particles are insidious and they’re everywhere,” said Dockery. “Trying to clean up the indoor environment has its limits, especially when you think about disadvantaged populations and people who don’t have the means to do so. The key is really to improve outdoor air quality—to cut down on the particle concentrations.”

The air is a lot cleaner these days than it used to be, the experts acknowledge—just not clean enough. In a 2022 article in the Harvard Heart Letter, Mittleman, professor of epidemiology, noted, “Even in relatively clean cities that comply with EPA air quality standards, relatively low levels of air pollution appear to increase the risk of heart attack and stroke.”

Ultimately, the experts would like to see policy solutions that tackle air pollution at its source. Nadeau stressed the importance of promoting the use of renewable energy and electric vehicles and of planting more trees, which can help remove pollutants from the air.

Added Rice, “The evidence is clear that fossil fuel combustion—especially from coal-fired power plants and transportation, especially old diesel trucks—is very unhealthy and deadly. Any policies that reduce fossil fuel-derived air pollution will benefit heart and lung health.”