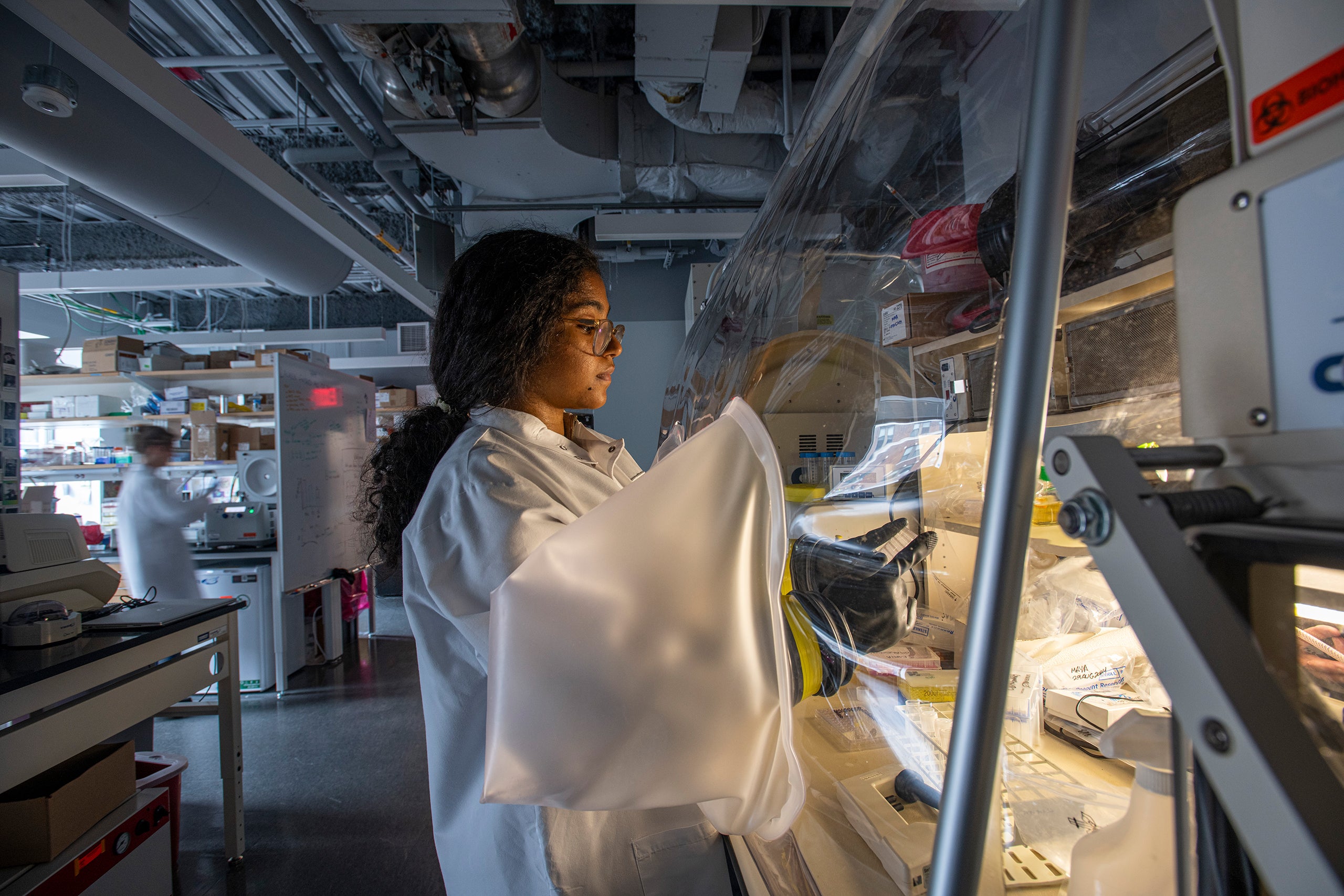

Gopinath Lab

Our mucosal surfaces are occupied by a robust and diverse ecosystem termed the commensal microbiome. When mucosal pathogens infect us, they first encounter our commensals before they encounter and activate our immune response.

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

655 Huntington Avenue,

Building FXB, Room 303

Boston, MA 02115

Immune Dynamics at Mucosal Surfaces: Pathogen, Microbiota, and Host Interactions

We are interested in studying the interactions between the commensal microbiota, pathogens and the host immune response in the one place they must necessarily meet – the mucosa. Studying host-pathogen interactions at the mucosa allows us to identify novel pathways and mechanisms by which we resist or tolerate infections. We have multiple projects aimed at studying the mechanisms by which pathogens activate and evade the mucosal immune response and how these interactions are modulated by the microbiota. Our goal is to generate and test new ideas for vaccine and drug candidates to better protect people against infectious disease.

Support Harvard Chan School

Every gift contributes to our mission of building a world where everyone can thrive. To learn more about how you can support The Gopinath Lab, please contact Carter Brown at chbrown@hsph.harvard.edu

Our Research

Unlike the intestinal microbiome, the vaginal microbiome consists of a smaller and more defined set of bacterial communities. The vaginal microbiome is also more consistent in people across the world. Changes in the vaginal microbiome have been linked to increased susceptibility to and transmission of sexually transmitted infections. We are interested in how vaginal bacteria, including health-associated lactobacilli, impact host immunity to sexually transmitted diseases.

We recently identified a family of anti-inflammatory small molecules produced by vaginal lactobacilli and depleted in people with vaginal inflammation and bacterial vaginosis.

The gut microbiome can influence distal sites in the body including the skin. We want to understand how the gut microbiome influences vaginal immune homeostasis. Conversely, it was recently discovered that genital herpes infections can result in viral infection of the enteric neurons in the colon. We will use this model to study how the vaginal immune response can prime and control immune responses to enteric viral infections.

We recently discovered that aminoglycosides (commonly used antibiotics) can induce antiviral gene transcription in dendritic cells, resulting in broad antiviral protection at the vaginal and nasal mucosa. We want to understand the intracellular signaling pathways involved, so we can build better antivirals.

Who we are

Publication highlights

- Vaginal lactobacilli produce anti-inflammatory β-carboline compounds

- Epithelial organoid supports resident memory CD8 T cell differentiation

- Intranasal neomycin evokes broad-spectrum antiviral immunity in the upper respiratory tract

- A framework for microbiome science in public health

- Cutting Edge: The Use of Topical Aminoglycosides as an Effective Pull in “Prime and Pull” Vaccine Strategy

- Topical application of aminoglycoside antibiotics enhances host resistance to viral infections in a microbiota-independent manner