Tuberculosis control efforts face headwinds, including U.S. aid cuts

Tuberculosis—its prevalence, its disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations, and complicated global politics that can thwart efforts to rein it in—was the focus of a series of events at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in February and March.

The events were centered around the School’s first “Big Read” book club pick: “Phantom Plague: How Tuberculosis Shaped History,” by veteran science and health journalist Vidya Krishnan. Krishnan was on hand for several of the events, which included panel discussions, Q&As, and discussion circles.

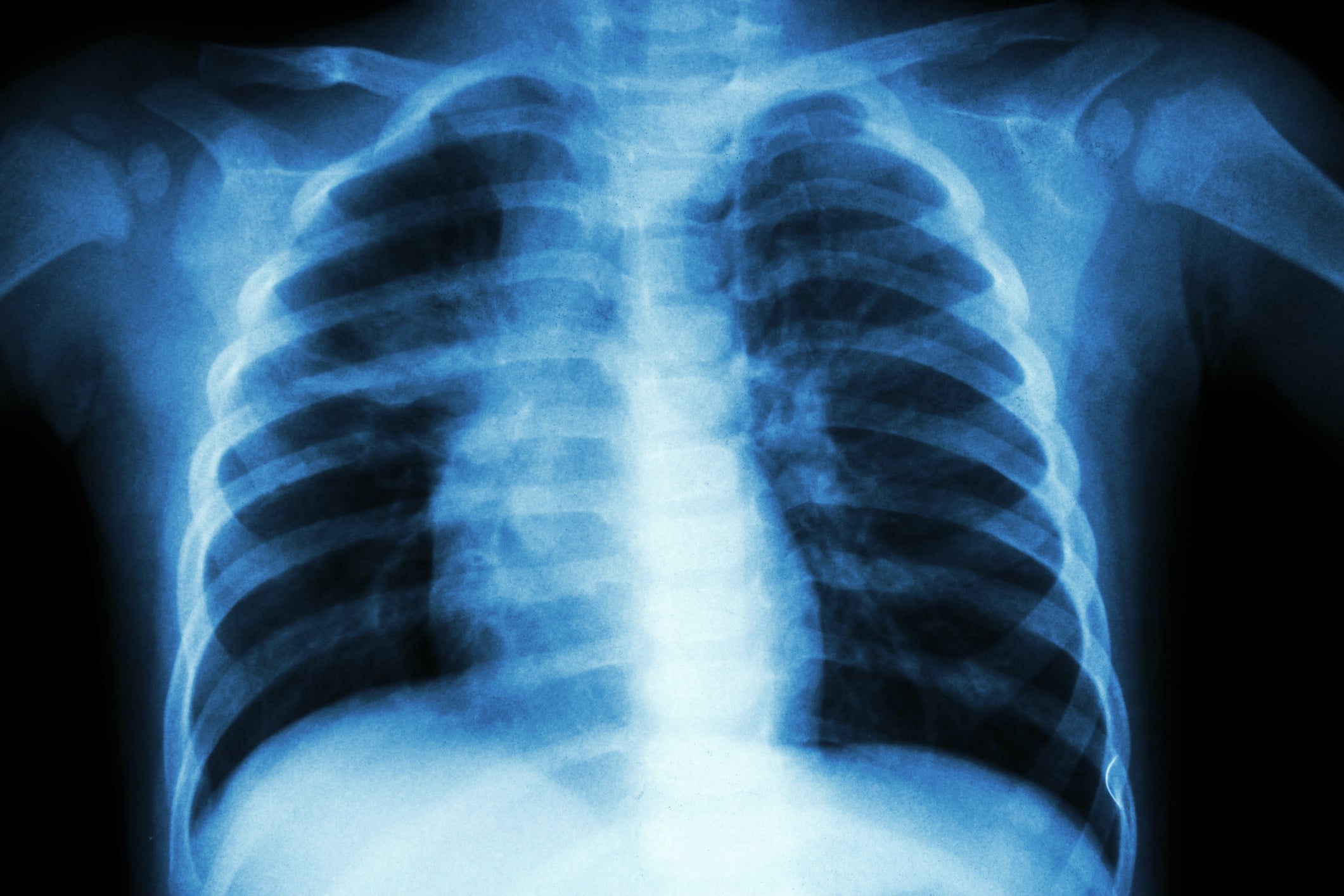

Experts at the various events made clear that TB is a daunting disease, tough to treat and tough to beat. It’s the leading infectious cause of death in the world. There are about 11 million cases and 1.5 million deaths each year. Sarah Fortune, one of several panelists at a March 6 Studio event that focused on TB diagnosis and treatment, put those numbers in context: “In 2020, globally, there were … a little more than a million and a half COVID deaths,” said Fortune, John LaPorte Given Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases. “And so that same order of magnitude of mortality, that’s happening every year around the world [from] a disease [TB] that we and many other people around the world kind of take for granted has been erased.”

At a March 3 online Q&A, Krishnan said that she felt compelled to write her book after meeting TB patients living in the slums of Mumbai—lower caste individuals who were suffering with their disease, often waiting weeks and months for treatment, getting treated improperly, or not getting treated at all. According to Krishnan, the treatment issues stem, in part, from a health system that exacerbates disparities, a patent system that keeps drug prices too high, and the increasing prevalence of multi-drug resistant TB. One of the focuses of her book is the story of a girl named Shreya Tripathi, who was diagnosed with TB in 2012 and whose family fought in court in India to get her access to an effective TB drug called bedaquiline. She eventually received the drug, but by that time it was too late and she died in 2018.

Stories are ‘like magic’

The importance of storytelling in public health was the focus of a March 4 Studio event featuring Krishnan on a panel along with Annie Brewster, a physician and founder of the Health Story Collaborative, and Predrag Stojicic, adjunct lecturer on health policy and management at Harvard Chan School and a community organizer.

Brewster spoke about how, after being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2001 and discovering shortcomings in the health care system, she realized that creating a platform for patients to share stories could help them deal with the “identity shift” that happens when they suffer an illness, trauma, or loss. “Our work is really about trying to create time and space for storytelling in health care with a therapeutic intent,” she said.

Krishnan discussed how, in her book, she wanted to provide information about the history of TB but also wanted to hook people into the narrative. So she included a number of little-known and colorful historical facts, which she described as “gold coins … something shiny” to engage the reader—such as the fact that before people knew what TB was, their fear about contagious diseases inspired tales about vampirism, including Bram Stoker’s “Dracula.”

Said Stojicic, “For me, stories and narratives are like magic. They turn moments into meaning. … A good narrative can kind of suck you in, can give you good laughs, good cries, and sometimes outrage you, but it leaves you with this feeling, oh, we went deep. We have to do something about it.”

Historian Emily Harrison, a lecturer in the Department of Epidemiology, who moderated the panel, agreed. “I think of stories as the organizing structure that can … turn understanding or knowledge or scholarship into power for change.”

Challenges in TB control

At the March 6 Studio event, Fortune and two other panelists—Carole Mitnick, professor of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School’s Blavatnik Institute, and Nicolas Menzies, associate professor of global health at Harvard Chan School—spoke about challenges and opportunities regarding TB control.

Mitnick noted that while TB treatment can be highly effective, it’s not an easy regimen—patients must take a combination of four drugs over the course of six months, and there are side effects. Given the length of care and the fact that many TB patients are disproportionately impoverished and living in resource-poor settings, “taking TB treatment may not be their first priority,” she said.

She added, “Until and unless we address [the] larger structures of resource distribution and conditions of living, I think we are unlikely to see additional major gains in TB.”

Menzies noted that global political changes, such as recent U.S. cuts to funding for USAID, could curtail TB control efforts. “What is happening right now will have major implications,” he said. “We know that interruptions in care can mean that individuals who have been diagnosed with TB may not complete treatment. They may develop resistance to the regimen, which would have otherwise been effective. People who have TB and don’t get diagnosed will go on to transmit to their family members.” Menzies added that slow progress made over the past 10-20 years in reducing TB prevalence could quickly be erased—and that if TB incidence rises, it will rise everywhere, including in the U.S. “TB is a disease that connects the world,” he said.

Hope on the horizon

On a positive note, Menzies said that scientific breakthroughs are on the horizon that could lead to better treatments, better diagnostics, and possibly a new vaccine. For those innovations to have impact, he cautioned, high-income countries like the U.S. need to partner with countries with high levels of TB. If such partnerships are maintained, “we can leverage … new innovations and actually can control TB,” he said. “This is a moment where things could go back, but things could also go really well—depending on what we do.”

Fortune pointed out that the importance of very basic interventions in fighting TB—such as food aid—“cannot be understated.” She cited the RATIONS trial in India, which found that providing food to people who were undernourished reduced TB incidence almost as well as the best vaccine candidate in current trials. “We globally have the ability for transformative action in TB [by providing food aid],” she said, “and gosh, we’d be feeding people, wouldn’t that be awesome, too?”