How airway ‘squeezing’ during asthma attacks triggers a cycle of worsening disease

During asthma flare-ups, a major symptom people experience is bronchoconstriction—when the muscles in the airway tighten and narrow, making breathing difficult. Now, new research from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health has shown that this mechanical “squeezing” of the airway can trigger responses in the epithelial cells—those that line the airway—that make bronchoconstriction worsen and persist, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that may contribute to asthma progression.

“Asthma is known as a disease of airway inflammation and recurrent bronchoconstriction,” said Jin-Ah Park, associate professor of airway biology. “However, most research has focused on inflammation, especially how immune cells and inflammatory molecules contribute to disease progression. Our new study highlights another important piece: Repeated bronchoconstriction itself can exacerbate disease.”

The study was published Dec. 12, 2025 in Nature Communications.

The Park lab identified that a protein called Hic-5, which plays a key role in epithelial cells, converts mechanical forces caused during bronchoconstriction—including muscle tightening and increasing cellular pressure—into biochemical signals that lead to the self-perpetuating cycle of worsening bronchoconstriction.

The researchers used both experimental and computational approaches to uncover their findings.

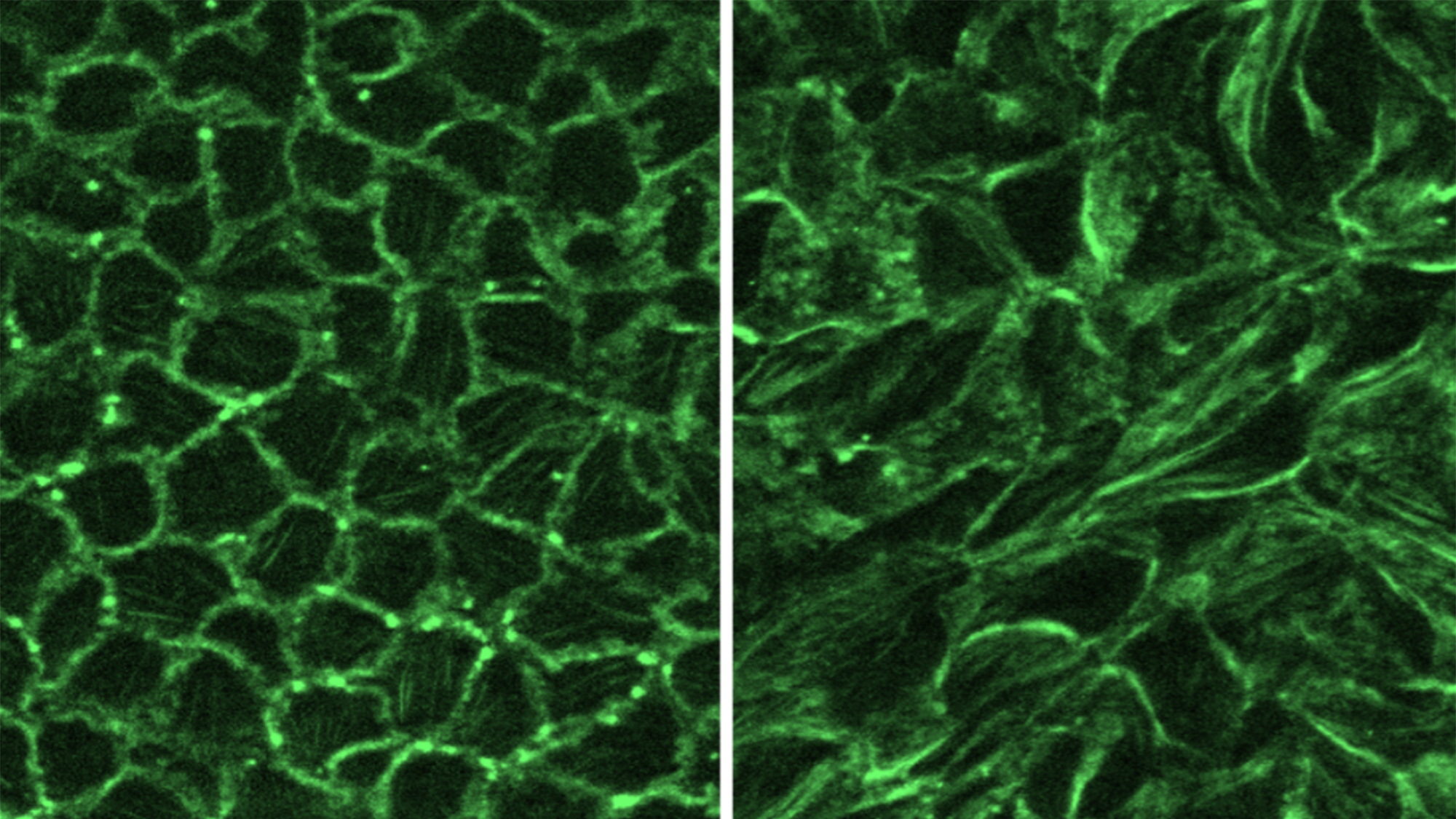

On the experimental side, they isolated airway epithelial cells from human donors, put them in culture, and then applied mechanical forces aimed at mimicking the squeezing that airway cells experience during asthma-induced bronchoconstriction. This squeezing of the cells induces Hic-5 expression, which promotes the formation of stress fibers, thereby increasing internal tension and activating biochemical signaling within the cells. The researchers also found that silencing Hic-5 expression eased the biochemical signaling that is capable of initiating bronchoconstriction.

On the computational side, they analyzed gene and pathway data to identify key molecules involved in the bronchoconstriction loop—which is how they identified Hic-5 as an important protein in the process. To ensure that their results were relevant to human disease, they validated their findings using publicly available human datasets from patients with asthma undergoing bronchoconstriction, which were reported by researchers at Mass General Hospital.

A path to reducing asthma deaths

Findings from the study could have significant public health implications, Park said. She noted that asthma is incurable and affects more than 350 million people worldwide. And although there are treatments available—focused on reducing the immune-cell activation and airway inflammation that are also major symptoms of asthma—up to 25% of patients respond poorly to current therapies. If bronchoconstriction isn’t well controlled, it can be deadly: The 2024 Global Initiative for Asthma report estimated that there are about 1,000 asthma-related deaths every day.

“Our findings suggest that reducing inflammation alone may not be enough to fully control bronchoconstriction during asthma exacerbations,” Park said. “If we can interrupt the mechanical-to-chemical signaling pathway that allows bronchoconstriction to sustain and amplify itself, it could open new strategies to improve symptom control, reduce severe attacks, improve quality of life, and potentially prevent asthma-related deaths.”

Park added that the findings could lead to new treatments for virus-triggered bronchoconstriction, such as that caused by rhinovirus or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which frequently occurs in people with asthma.

Other Harvard Chan School co-authors of the study included first author Chimwemwe Mwase, Wenjiang Deng, Hyo Jin Kim, Jennifer Mitchel, Thien-Khoi Phung, Michael O’Sullivan, and Adam Haber. Former research fellow Joel Mathews also contributed.

Read the study: Hic-5 drives epithelial mechanotransduction promoting a feed-forward cycle of bronchoconstriction