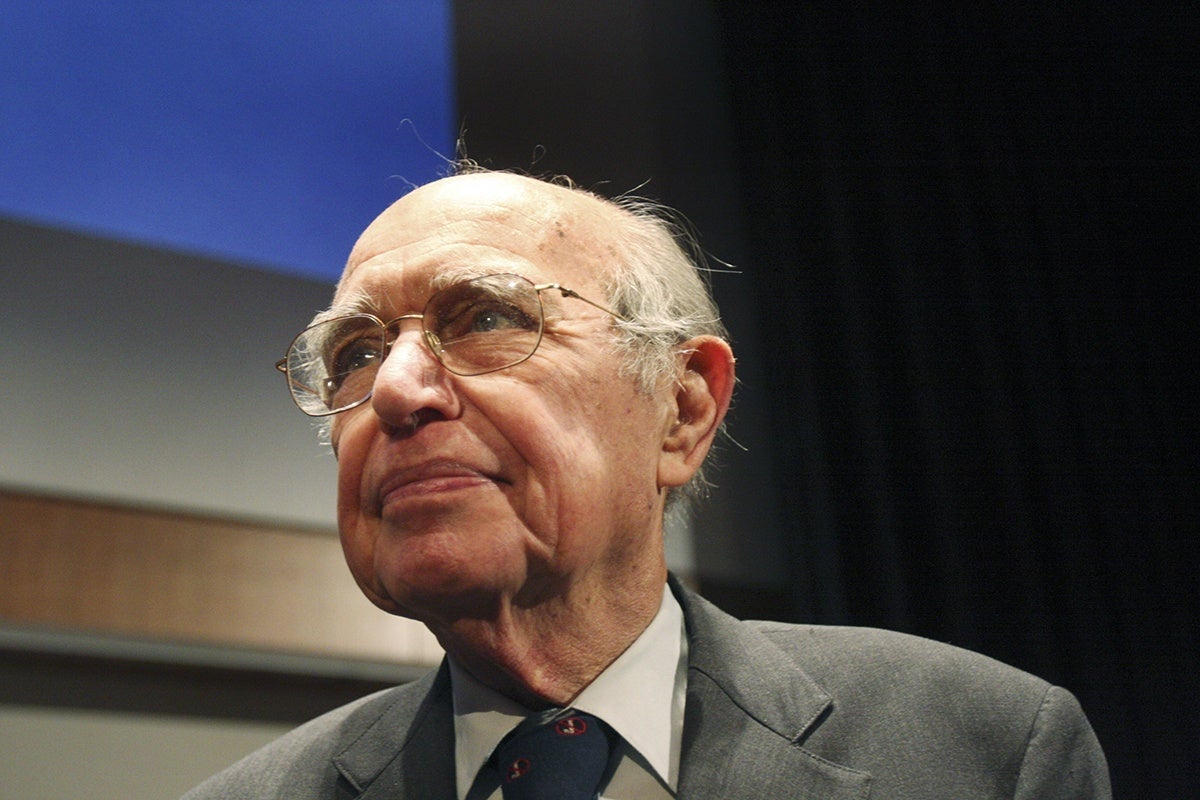

During Head Start Awareness Month, remembering Julius Richmond, its first director

Richmond, who held several prominent roles at Harvard, was a giant in the field of child health and development

October 8, 2021 – When Linda Villarosa met Julius Richmond at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health 30 years ago, they got into a conversation about Head Start, the federal program aimed at breaking the cycle of poverty through the care and education of young children from low-income families.

The conversation brought them both to tears.

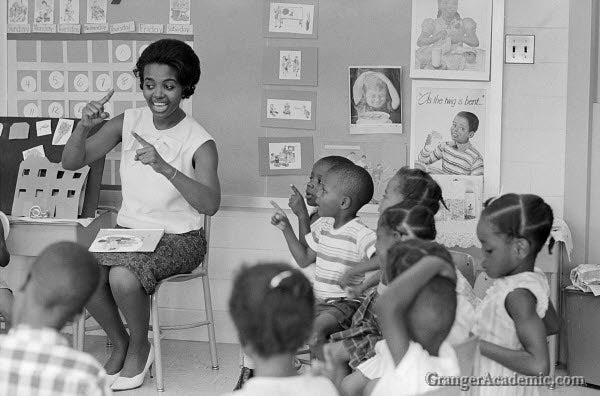

At the time, Villarosa was spending a year as a health communications fellow at Harvard Chan School, and Richmond was a professor emeritus. The emotion in their long-ago conversation had to do with the fact that Richmond, who died in 2008, was Head Start’s first director, and Villarosa—a journalist and author who writes about race, inequality, and health—was among the 561,000 children in its first cohort in 1965, when she was five years old.

“It was a huge deal to be going into Head Start,” recalled Villarosa, who grew up on Chicago’s South Side, a predominantly Black community that has declined over time due to discrimination, neglect, and disinvestment. “I remember my mother talking about [Head Start] in really glowing terms.” Villarosa told Richmond how much it meant to her family that she was in the first Head Start group. It allowed her mother to work while knowing that her young daughter was gaining valuable education and skills.

October is National Head Start Awareness Month, when the nation marks the program’s contributions. Reflecting on Richmond’s contributions to Head Start, to the field of early child development at Harvard and beyond, and to public service, colleagues who knew and worked with him speak in superlatives.

“He was a soft-spoken, gentlemanly hurricane,” recalled Jack Shonkoff, the Julius B. Richmond FAMRI Professor of Child Health and Development, who for 15 years has directed the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, which focuses on building and leveraging the science of early childhood development to help improve real-world outcomes for young children facing adversity. Richmond was the driving force behind establishing the Center at Harvard and in recruiting Shonkoff, who previously served as dean of Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management.

“He was so fiercely dedicated to the well-being of children,” said Shonkoff. “By necessity, he operated in an environment with a lot of very high-powered aggressive people, and he was always the voice of calm and wisdom and guidance. He was as unrelenting in his commitment to impact as anyone else, but had an amazing way of rising as a leader in a group to get things done.”

Harvard Chan School’s highest honor is named for Richmond. The Julius B. Richmond Award recognizes individuals who, like Richmond, have promoted and achieved high standards for public health conditions in vulnerable populations.

Intellectual powerhouse, social reformer

Richmond’s career path reflects his commitment to both scientific research and public service. Trained in pediatrics and child development, he became chair of the Department of Pediatrics at SUNY Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse in 1953 and later rose to the position of dean. During his time at SUNY Upstate, Richmond conducted research on the cognitive development of young children growing up in poverty, finding that poor children fell behind after age one. That work led to Richmond’s appointment in 1965 as the first director of Head Start, which was established as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty.” Richmond also served as assistant director for health affairs of the Office of Economic Opportunity.

After his initial stint in government service, Richmond returned to Syracuse, then moved in 1971 to Harvard University, where he held several prominent roles over a nearly 20-year span. At Harvard Medical School, he held professorships in two departments, Child Psychiatry and Human Development, and Preventive & Social Medicine. At Harvard Chan School, he was professor of health policy from 1981–88. He also served in other roles, including as director of the Judge Baker Guidance Center in Boston, a nonprofit mental health organization that works with Boston’s juvenile courts, and as chief of psychiatry at Children’s Hospital Boston.

From 1977 to 1981, Richmond re-entered the public sector, serving as U.S. Surgeon General and Assistant Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services. As Surgeon General, he issued the momentous 1979 report Smoking and Health and set targets for the health of the American public with the Healthy People report, first published that same year.

Historian Allan Brandt’s office used to be down the hall from Richmond’s on Huntington Avenue in Boston’s Longwood Medical Area, and for about two decades the two men met nearly every morning for coffee. Calling Richmond “one of my most important mentors,” Brandt said that Richmond was unusual in his ability to toggle back and forth between government and universities. “He became a real Washington insider and policy thinker and policy maker, and that is pretty unusual for somebody who was in so many ways an intellectual scholar and researcher,” Brandt said. “He would take insights from his own research and think about what their implications were for major social reform and public programs. He was incredibly savvy from a political point of view.”

Life-changing program

In Shonkoff’s opinion, Richmond’s efforts during the early days of Head Start served as an anchor for the entire field of early childhood intervention. “Head Start was a magnificent example of bringing together the best minds in the country in terms of the underlying science of child health and development at that time and a critical mass of advocates and government leaders who brought all of their perspectives together and created a new program, and in that sense created a new field of early childhood intervention that is still standing half a century later,” he said.

“Julie,” as Richmond was known to his friends, relished hearing from people whose lives had been improved by Head Start, recalled Brandt. “Every once in a while, Julie would get a letter from someone in their late twenties or early thirties, writing personally to thank him, telling him their stories about how the opportunities that Head Start created for them had radically changed their lives and circumstances,” said Brandt. “It was incredibly affirming for him, of having done something that people believed and understood was so important in who they’d been able to become.”

Villarosa is one of those people. She said, “I write about communities of color and Black communities in the U.S., and look at how they’ve been harmed or helped by government policies, and to me, Head Start is a personal and professional success story. I’m proud to be a product of it.”

Photos

Julius Richmond: Kris Snibbe/Harvard University

Linda Villarosa: Nic Villarosa

Jack Shonkoff: Fred Field

Allan Brandt: Kevin Grady/Radcliffe Institute

Head Start Program: Thomas J. O’Halloran/Granger Academic