The Good Life: A Discussion with Dr. Robert Waldinger

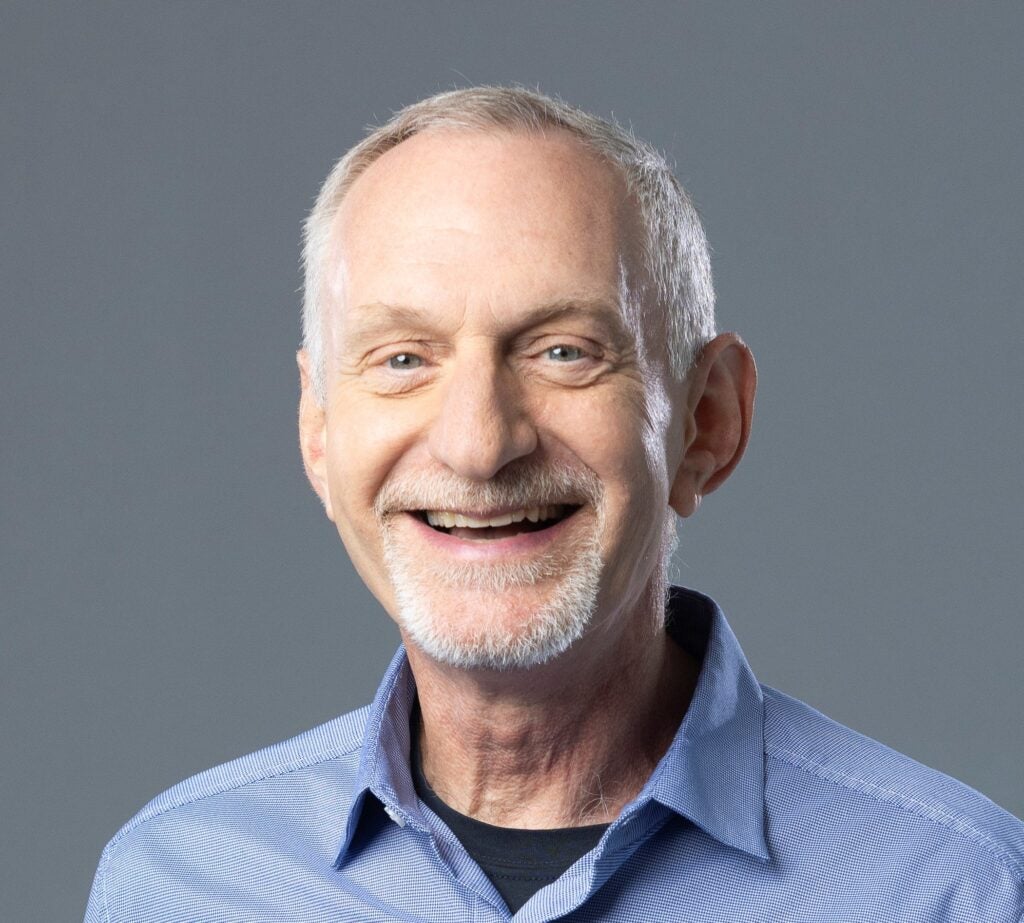

What brings us happiness? What do we need to feel as though we’re living a good life? Dr. Robert Waldinger (pictured right), Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and Director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development, the longest running scientific study of adult life ever conducted, has spent his career searching for the answers to these questions. On February 27th, Dr. Waldinger gave a virtual talk on his new book, The Good Life, a New York Times Bestseller which shares key findings from the Study of Adult Development. Dr. Waldinger was introduced by Dr. “Vish” Viswanath, Director of the Lee Kum Sheung Center for Health and Happiness, then gave a presentation, followed by an audience Q&A. The webinar was well attended, with an audience of more than 800 individuals, hailing from 44 different countries.

What brings us happiness? What do we need to feel as though we’re living a good life? Dr. Robert Waldinger (pictured right), Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and Director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development, the longest running scientific study of adult life ever conducted, has spent his career searching for the answers to these questions. On February 27th, Dr. Waldinger gave a virtual talk on his new book, The Good Life, a New York Times Bestseller which shares key findings from the Study of Adult Development. Dr. Waldinger was introduced by Dr. “Vish” Viswanath, Director of the Lee Kum Sheung Center for Health and Happiness, then gave a presentation, followed by an audience Q&A. The webinar was well attended, with an audience of more than 800 individuals, hailing from 44 different countries.

Dr. Waldinger began by exploring what people think makes a good life. Many across the world, especially millennials, believe that the answer can be found with fame and fortune. In a recent survey of millennials, when asked what they wanted in their adult life, over 80% said they wanted to get rich, 50% said they wanted to get famous, and 50% said they wanted high career achievements.

However, studies show that as many western countries, including the US, have become wealthier, general happiness levels have decreased. $75,000 a year average household income is the level at which happiness seems to peak— the level at which the basic economic needs of food, housing, healthcare, child support, etc. can be met. When people’s annual income became higher than that sum, their happiness levels didn’t go up much. The difference between $75,000 and $75 million was hardly significant.

Dr. Waldinger believes that the reason many hold this false belief in the power of money to improve happiness is because the good life is defined for us, not by us. This is a result of the digital revolution, social media, unrealistic standards, and omnipresent advertising. Ads tell us that consumption ought to make us happy, that we ought to look and act a certain way. We judge our everyday lives against the curated lives of others, and young people, who are more deeply entrenched in digital media than any generation before them, are particularly vulnerable to this constant self-comparison. “As a mentor of mine once said,” stated Dr. Waldinger, “‘we are always comparing our insides to other people’s outsides.’”

The Harvard Study of Adult Development

So what do we really need for a good life? As Director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development, Dr. Waldinger was ideally placed to search for an answer. This 85-year study started in 1938 as two studies. One followed a group of 19-year-old Harvard students, while the other followed a younger group of juvenile delinquents. Both groups were exclusively white, male, and based out of Boston. The two studies were combined to make up a group of 725 men. As time passed, their wives were brought into the study, and then their children. The group even included John F Kennedy. Participants’ physical, mental, and emotional health were studied. They were photographed, audiotaped, and videotaped. Their blood was drawn, their brains were scanned, and their DNA was studied.

The study found that the people who stayed healthiest and lived longest were the people who had the strongest connections to others. The warmth of these connections had a direct positive impact on their health and well-being. Good relationships meant participants were less likely to develop heart disease, diabetes, or arthritis. Broader social networks and more social activity resulted in later onset and slower rates of cognitive decline. The study even found that married people lived longer—an average of 5-12 years longer for women, and 7-17 years longer for men.

Interestingly, the study also found that participants became happier as they aged. From middle age onward, participants paid more attention to positive information than negative information, remembered the past more positively, became more selective about how they spent their time, and increasingly savored the present moment. Dr. Waldinger’s explanation for this trend was that “When we sense that time is limited, emotional well-being becomes a priority.” There is a downside to this, however—older brains are more responsive to positive information, and tend to disregard negative information, making them more susceptible to scams.

When the first round of participants were in their 80s, the interviewers asked them what they wished they had done differently, and what they were most proud of. The men replied that they wished they hadn’t spent as much time at work, but with the people they cared about. The women replied that they wished they hadn’t worried about what people thought of them. For both genders, their proudest achievements all had to do with relationships. Participants were proud of being a good parent, partner, friend, or mentor.

These findings affected Dr. Waldinger personally. He realized that he had to listen to his own research, and so instead of working 24/7, he began to intentionally reach out to his friends, telling him that he was thinking of them, inviting them to go out for a walk or get dinner. While he was proud of his work, he realized that his greatest source of satisfaction wasn’t the academic awards he had received, but instead maintaining vibrant connections with others.

Expounding on this, Dr. Waldinger added that when it came to work and relationships, he understood that it couldn’t be either or. He explained that people need enough money to be financially secure, to support themselves and their families. But the people who sacrifice everything for work end up feeling like they’ve given up too much in their lives. It may be tempting to focus on money or achievements because they’re measurable, and we tend to prioritize what we can measure. Relationships change all the time, and cannot be measured in the same way; but this does not make them any less important.

In terms of spending money to achieve happiness, Dr. Waldinger recommended paying for experiences, rather than material things. “The best things in life aren’t things,” he explained. “Material things lend themselves to comparisons. But experiences either strengthen pre-existing relationships with people, or help us meet new people.”

The Loneliness Pandemic

Developing and strengthening relationships with others is a skill that has decreased in the general US population since the 1950s, with the introduction of the television. Over the last 25 years, people have become half as likely to join clubs and civic organizations, while family dinners and vacations are down by a third. In 1983, 12% of Americans lacked a confidant, someone they could speak to about personal matters, while in 2003, 25% lacked a confidant. In a global poll of 15 million workers, only a third said they had a best friend at work, and of those, only 1 in 12 said they were engaged in their job. Half of CEOs report feeling lonely. Dr. Waldinger and many others believe that this loneliness pandemic was accelerated by the digital revolution. “We’re all on our phones, on our screens, so much of the time that we neglect each other, and we neglect the world around us.”

Studies have found that loneliness is as powerful a predictor of poor health as smoking half a pack of cigarettes a day, having high blood pressure, or being obese. Loneliness results in earlier cognitive and physical decline, stress-induced hypertension, impaired sleep, heightened cardiovascular reactivity, decreased immune function, and chronic inflammation.

How We Can Fix It

Dr. Waldinger began with a quote from one of his Zen teachers, John Tarrant, stating “Attention is the most basic form of love.” He went on to explain that “our undivided attention is the most valuable thing we have to give each other. It is also the most difficult thing, these days, to give each other, because screens are so programmed to take us away from each other. The path of least resistance seems to be driving us towards increasing social isolation, so we need to be intentional in structuring our lives both at home and at work to counter this trend.”

Of course, there are other factors to consider, such as where an individual is on the scale of introversion to extroversion. Introverts may only need a few relationships, and become stressed out by too many, while extroverts need a wider circle. “Our culture tends to glorify extroverts, which is silly,” said Dr. Waldinger. “Other cultures glorify a more contemplative approach to life.” The answer to finding a good life isn’t one size fits all.

Then there is an individual’s baseline level mood to consider. People can have the exact same circumstances, and some can happier and others sadder. Dr. Waldinger explained that about 50% of happiness comes from genetically based, temperamental factors, about 10% comes from life circumstances, and about 40% can be changed.

As the webinar came to an end, Dr. Viswanath read a final comment from an attendee. “It seems that we are discovering things that women have always understood, valuing relationships and loving our people.” Dr. Waldinger responded that there had been people who responded to his TED talks with “duh”. He explained that women are typically socialized to care more about relationships. “I am not revealing something to this world that’s a shocker,” he concluded. “We just now have good scientific data to back up what our grandmothers always knew and were telling us all along.”

If you missed the seminar, you can watch a recording here.

Written by Ayla Fudala, Communications Coordinator