Rio’s Schools Say No to Ultra-processed Foods

Luiza Lima Vieira is a Rose Service Learning Fellow and a Master of Public Health candidate in Nutrition

Starting the Journey

When I landed in Rio de Janeiro this summer, I thought I knew what my fellowship project would look like. I pictured myself sitting in classrooms, chatting with students, parents, and school staff about their new school lunches. I wanted to hear their perspectives on the recent law that banned ultra-processed foods and how it had impacted their school food environment. I pictured myself learning about people’s experiences and the wonderful implications of the law, but reality, of course, had other plans.

My first challenge came quickly: getting research approval took much longer than expected, which meant I couldn’t dive straight into conducting interviews with students, parents, or staff. At first, this was frustrating as I was eager to be with the children and see how the new school food law was unfolding on the ground. But as I learned, research (and life) rarely goes as planned. Therefore, instead of starting at the schools, I began my research online, talking to NGOs, nutritionists, lawmakers, and revising a large amount of policy documents in an informal way. I was obtaining data, conducting a general evaluation of how this law came to be. Surprisingly, that detour opened my eyes to the bigger picture: how much negotiation, creativity, and persistence it takes to turn a bold idea like banning ultra-processed foods into reality.

Learning in the Field

Learning to adapt was the biggest takeaway I took from the field. Like many field projects, my path was full of surprises. The delay in my research approval was something I had not planned for; therefore, I found myself struggling with innovative ways to carry out a project where I would incorporate community voices, while also fulfilling my Practicum requirements. I decided to immerse myself in policy design and understanding how the early implementation of a food ban is carried out.

This shift, while challenging, gave me a deeper appreciation of how public nutrition policies are made. I realized that the journey to changing what’s on a child’s plate begins long before the school lunch is served. It involves political debate, institutional negotiations, and industry pushback. Learning about the creation of this law sparked a new interest in me regarding policy making, which led me to join the Food Policy and Law Clinic at Harvard Law School this semester.

To incorporate community voices, I decided that I must visit the schools. While I wouldn’t be able to conduct formal qualitative research, I would still visit the school food environment and report my informal field findings. To eventually reach the students, I relied on a snowball approach: each conversation with an NGO leader or policymaker led me to new contacts, until I finally secured a meeting with the Municipal Department of Education, granting me permission to visit schools. These visits were an essential part of my experience, reminding me of the value of resilience, relationship-building, and listening to community voices.

Early Findings

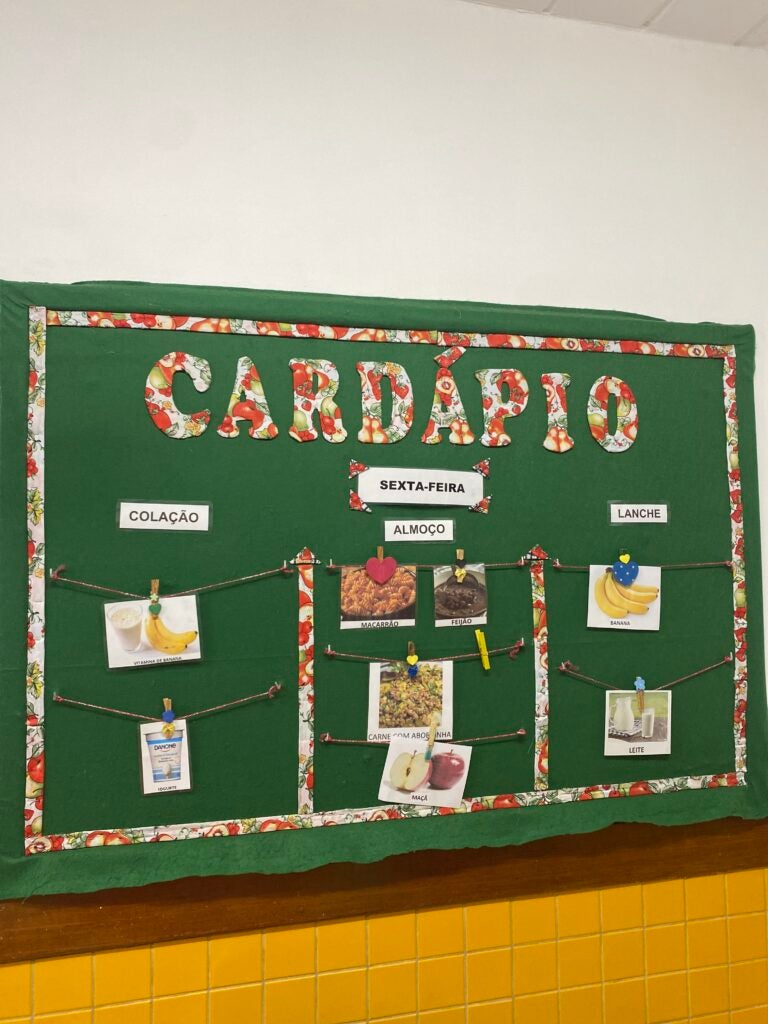

When I finally set foot in the schools, I saw the impact of the law beginning to take shape. Now I understood the preparation and was ready to eat the food. Breakfast and lunch menus had shifted away from packaged snacks and sugary options toward freshly prepared, traditional foods. School nutritionists and cooks spoke with pride about their role in this transition, and their commitment to children’s health was undeniable. It was a powerful reminder of why Brazil’s school feeding program is admired worldwide.

But I also saw the hurdles up close. It was expressed to me that some parents were unsure about the new rules, partly because communication with families has been uneven. Fresh food is harder to source and distribute consistently, especially in a system as large as Rio’s. And, as expected, the processed food industry has not remained quiet, continuing to exert pressure against the law’s enforcement. These early lessons made it clear that progress is possible, but only with ongoing support and strong political and social systems to back it up.

This experience taught me not only about school nutrition policy but also about myself as a researcher. One of my biggest takeaways was learning to embrace flexibility: when original plans became impossible, I had to find new ways to collect insights while keeping my work meaningful. I also came to see that Brazil’s leadership in school nutrition is not accidental. The Brazilian school food program stems from the collective effort of teachers, nutritionists, policymakers, and civil society organizations, all deeply committed to protecting children’s health and preventing poor outcomes from an early age.

Key Takeaways

- Brazilian schools are already a model: Many public-school meals here are healthier than those in wealthier nations, thanks to strong national policies.

- Collaboration is essential: Change only happens when educators, nutrition professionals, NGOs, and government officials share responsibility.

- Nutrition education makes a difference: From school gardens to classroom lessons, food education is being integrated into learning, even with limited resources.

- Politics and culture matter: The law reflects a broader belief that protecting children’s health is a political and cultural priority.

- Brazil can lead global nutrition: With its expertise and commitment, Brazil has the potential to inspire other countries to rethink school food.

Looking Ahead

The first signs are encouraging, but sustaining momentum will require intentional steps. Clearer communication with families, more opportunities for parents and students to share feedback, and better use of research platforms could all strengthen trust and engagement. Robust monitoring across health, education, and food sectors will also be key to ensuring the law fulfills its promise. More broadly, this fellowship opportunity reminded me that food policy is never just about what’s on the plate; it is about politics, culture, persistence, and people working together for a common cause. The ban on ultra-processed foods in Rio’s municipal schools is still in its early days, but it already signals something bigger: Brazil’s determination to promote children’s health as a priority. That, to me, is the true lesson, and one that I wish to carry out forward.