What if we’re measuring only the tip of the iceberg in air pollution?

A column in the new publication, Nature Health, on “The human airborne exposome,” suggests that current methods of measuring and studying the health impacts of air pollution may be inadequate. Peng Gao, Assistant Professor in the Department of Environmental Health, authored the Perspective, which was published in the premier issue of Nature Health.

Dr. Gao explains that, for decades, air-pollution research and regulation have centered on six criteria air pollutants. But real-world inhalation exposure is far broader and more complex: thousands of organic compounds, dozens of inorganic substances, and vast biological components, creating highly individualized exposure profiles that vary dramatically even between neighbors.

In this Perspective, Dr. Gao proposes a framework that integrates:

- Mixture-based approaches that reflect real-world co-exposures

- Advanced personal monitoring to capture individual-level variability

- Systems biology and multi-omics to connect exposures to mechanisms and disease pathways

- Shift from single-pollutant regulation to multi-pollutant/source-based strategies, enabled by a phased roadmap with practicable success metrics.

This roadmap could transform how we understand complex diseases, from neurodevelopmental disorders to cancer to cardiometabolic conditions, and enable precision prevention and intervention for vulnerable populations.

“Air pollution research has long focused on a handful of regulated indicator pollutants, yet people breathe in thousands of chemicals and biological agents every day. This article argues for a fundamental shift toward the human airborne exposome, the full mixture we actually inhale daily, and provides a practical roadmap to measure it and connect it to biology,” says Dr. Gao. “The ultimate goal is precision environmental health monitoring: identifying exactly which components and sources matter most for each region and individual, so that prevention and intervention strategies can become both more effective and more equitable.”

Read the paper in Nature Health here.

Last Updated

COP30 Gives Cause for Cautious Climate Optimism

Mary B. Rice, Director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at Harvard Chan School (Harvard Chan C-CHANGE) recently returned from a trip to the UN Climate Change Conference, COP30, in Belém, Brazil, where she spoke on two panels.

Dr. Rice shared her perspectives on the conference on LinkedIn writing, “While the U.S. is sitting out of this year’s negotiations and global climate pledges are falling short, progress is taking hold from the bottom up.” Dr. Rice shared, “That’s why scientists and health professionals must keep showing up at COP and everywhere decisions are made about climate mitigation and adaptation, even at the most local level, to relay the message that climate solutions are health solutions.”

Dr. Rice was among a small delegation of 10 Harvard students and several faculty who attended COP30, this year, as covered in the Harvard Crimson.

Fossil fuel pollution is just like secondhand smoke, as it causes immediate and long-term injury to the respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurologic systems. Vested interests may try to convince us otherwise, but reducing our reliance on fossil fuels cleans up the air and ushers in immediate health benefits for people of all ages.

While the United States government did not officially participate in COP30, many local and state legislators were part of the conversations held at this year’s event, including California Governor Gavin Newsom, and Nylah Oliver, Director of Sustainability for the City of Savannah, Georgia. One panel, America is All In, featured experts from across the US to discuss creative and action-oriented approaches to climate mitigation in the US. Dr. Rice was among those experts, and emphasized that there is reason for hope when it comes fighting climate change.

Dr. Rice compared the local efforts to mitigate climate impacts to the grassroots efforts that were once used to eliminate tobacco smoke in public places. “Cities are redesigning streets to cut traffic pollution, communities are transitioning away from fossil fuels, and public–private partnerships are improving access to healthy, sustainable food. What these interventions share is that they’re all driven by local leadership,” said Dr. Rice.

“We experienced something similar with tobacco smoke,” explained Dr. Rice. “For decades, powerful interests clouded the science, and people doubted the harm of smoking. But as evidence became impossible to ignore, it was local action—city by city, state by state—that led to nationwide indoor smoking bans. Fossil fuel pollution is just like secondhand smoke, as it causes immediate and long-term injury to the respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurologic systems. Vested interests may try to convince us otherwise, but reducing our reliance on fossil fuels cleans up the air and ushers in immediate health benefits for people of all ages”

“We did it with tobacco smoke. We can do it again with fossil fuel pollution—city by city, community by community,” said Dr. Rice.

Read more about Dr. Rice and Harvard’s participation at COP30 in the Austin Chronicle and the Harvard Crimson.

Last Updated

Food Allergy News & Updates

In this issue, I highlight our ongoing research on food allergies and the dedicated scientists in my lab who are advancing this field during these challenging times. Advancing science requires curiosity, patience, and resilience—to continuously confirm, build upon, or challenge prior findings. For more than 30 years, our work has focused on preventing, diagnosing, and treating food allergies, and over time, our efforts have led to meaningful clinical progress. We prioritize collaborations and continue to work with Stanford, Univ of Chicago, Northwestern, FARE, London, Zurich, Munich, Denver, Cincinnati, and others.

Here are some of the clinical trials that are underway focused on preventing and treating food allergy. There is growing evidence that food allergy begins very early in life. This is the focus of our SEAL and Project Viva studies. We are also evaluating new approaches to treating food allergy. Although oral immunotherapy (OIT) has been shown to be effective, several barriers remain, including allergic reactions during treatment, lengthy treatment duration, and the need for frequent clinic visits. In addition, while most patients achieve desensitization, this effect is often temporary and may diminish when the allergenic food is no longer consumed on a regular basis. To address these challenges, we are exploring the use of biologics (with or without OIT) to improve safety, enhance efficacy, and achieve lasting tolerance.

Thank you for your continued interest and support in the work we do in Food Allergy.

Best,

Principal Investigator, Allergy, Extreme Weather, & Exposomics Lab

John Rock Professor of Climate and Population Studies

Chair, Department of Environmental Health

In this issue:

Research Updates

SEAL (Stopping Eczema and Allergy Study)

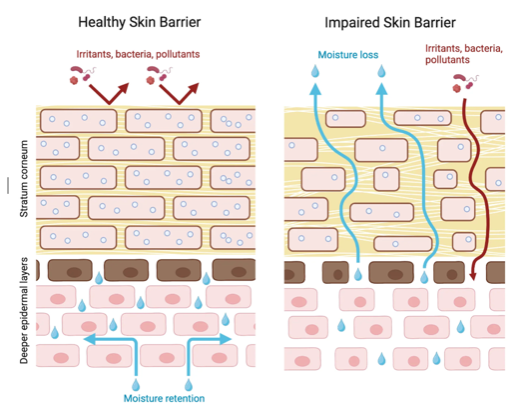

What causes some individuals to become allergic while others remain tolerant? Part of the answer lies in our genes. For example, those with a mutation in the gene, filaggrin, which codes for the skin barrier protein, are at much higher risk of developing allergies. Interestingly, they are not just at risk of developing eczema which is an allergic skin disorder, they are also at risk of developing other allergies diseases such as food allergies, allergic asthma, or allergic rhinitis.

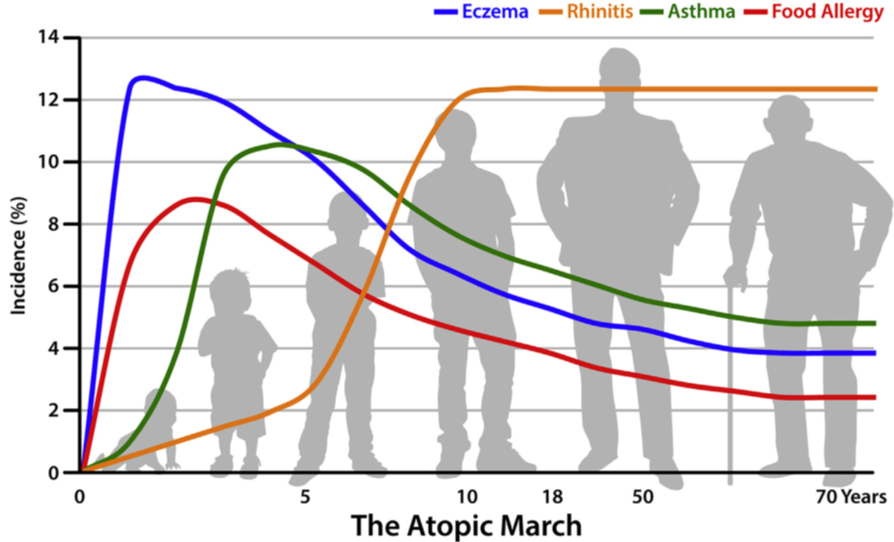

Another interesting observation is that most individuals with one allergy are at greater risk of developing other allergies, and that there appears to be a sequential order by which these allergies develop. For example, eczema is often the first allergy to develop, often in early infancy generally followed by food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and allergic asthma. This sequence of manifestation of allergic diseases has been termed the Atopic March (see Figure 1 below)

These observations led to the hypothesis that allergic sensitization may occur when inflamed and/or disrupted skin are exposed to environmental allergens and that the different allergies are varying manifestations of the same disease in different organ systems with a common underlying mechanism. Preliminary evidence suggests that by improving skin barrier integrity we may potentially reduce eczema and other allergies.

We are therefore conducting a large multicentered 2-year study called SEAL (Stopping Eczema and ALlergy study) to determine whether early intervention with skin moisturizing agent with a trilipid moisturizer in a high-risk infant group with eczema or dry skin can reduce the severity of eczema and decrease risk of developing food allergy. A trilipid moisturizer is one that mimics the skin natural lipid composition as well as physiological pH. These infants will be compared to two control groups of infants, one with no intervention and the other receiving a standard (non trilipid) moisturizer. The study is being conducted at four centers in the USA and one center in the UK. We have currently recruited 398 infants, of whom 397, 241, and 139 have completed baseline, 12 month, and 24 month visits, respectively. Learn more about the study here.

Project Viva

Does a maternal diet influence risk of food allergy? Project Viva is a ground breaking longitudinal research study of mother-child pairs that was started in 1999 to find ways to improve the health of mothers and their children. The study examines the effects of mother’s diet, as well as other factors during and after pregnancy, on child health outcomes, including food allergy.

For example, the information collected enables us to investigate the effects of diet on child development and obesity, and how diet and the environment influence the development of asthma and allergies in children.

Comprehensive dietary and environmental assessments in pregnancy, prospective follow-up, and well-characterized allergic outcomes are being conducted. Prior analyses using this cohort have demonstrated robust associations of prenatal diet with growth, obesity, and asthma, underscoring feasibility.

A total of 2128 babies born between 1999 and 2003 have been enrolled into Project Viva since 1999, and many are still actively engaged with the study. Learn more about the study here.

OUtMATCH

The Omalizumab as Monotherapy and as Adjunct Therapy to Multi-Allergen OIT in Food Allergic Participants (OUtMATCH) study is a clinical trial that was conducted across 10 centers in the United States. The clinical phase of the trial has been completed, and data are continuing to being analyzed.

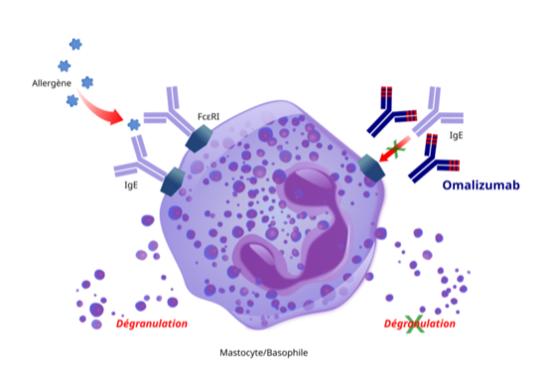

Omalizumab has been approved for asthma, chronic urticaria, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, and for food allergy. For patients with IgE-mediated food allergies, treatment is designed to reduce the risk of harmful allergic reactions. It does not eliminate food allergies or allow patients to consume food allergens freely. However, its repeated use will help reduce the health impact if accidental exposure occurs.

Omalizumab targets a key antibody, IgE, that is common in many allergic diseases. In individuals who are sensitized to allergens, IgE can be found attached to a receptor on certain immune cells (mast cells or basophils). When an individual encounters an allergen, the allergens trigger IgE on mast cells to release inflammatory molecules such as histamine. Omalizumab can preempt the release of histamine by blocking the ability of the allergens to trigger histamine release.

Oral immunotherapy (OIT) has been used successfully for desensitizing individuals with food allergy so that individuals do not react to allergens. However, it is time consuming, labor intensive, often requiring many trips to the allergy clinic. Palforzia, a standardized peanut protein powder has been approved for use in patients with peanut allergy. However, for those with other food allergies there are currently no FDA approved products. Additionally, OIT is not a cure as individuals often become allergic again after discontinuation of treatment. Its main mode of action is by upregulating IgG4, a molecule that blocks IgE. With prolonged treatment, IgE also decreases. Decreases in a number of proinflammatory cells and molecules are also observed with treatment.

This study follows up previous successes with omalizumab and oral immunotherapy in those with multiple food allergies. The study was designed to answer the following three main questions:

- Does taking omalizumab for a certain length of time stop or decrease allergic reactions to peanut and other common food allergens?

- How does a short course of omalizumab combined with multi-allergen oral immunotherapy compare with a longer course of omalizumab in decreasing allergic reactions?

- After participants stop both treatments, are they able to eat peanut and the 2 other foods in the form that is normally eaten?

A total of 177 adults and children were enrolled in the study. The study found that omalizumab treatment for 16 weeks was superior to placebo in increasing the amount of peanut and other common food allergens that individuals could consume. Molecular changes associated with desensitization was observed in the omalizumab group but not in the placebo group. These results have been published. Other analyses and publications are in progress. Read more about the study here.

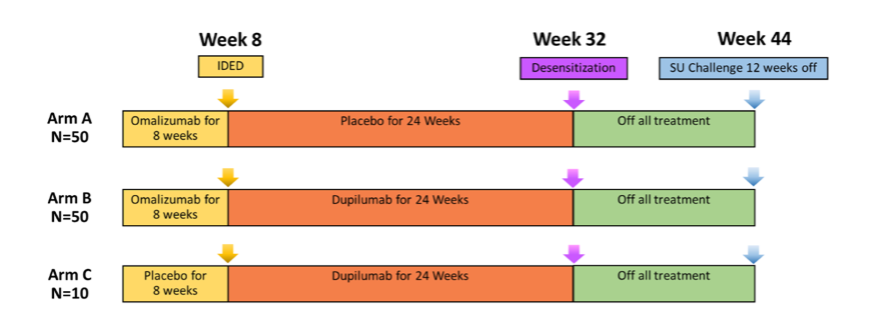

COMBINE

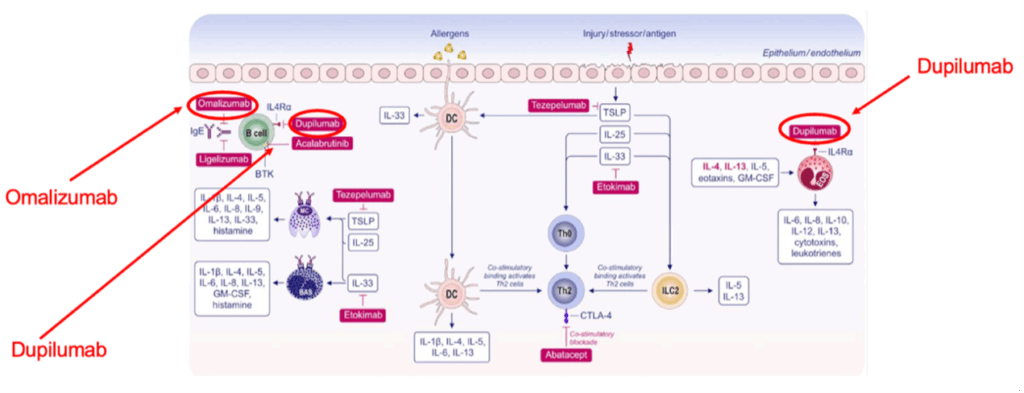

COMBINE is a clinical trial that is evaluating the safety and efficacy of using 2 biologics (dupilumab and omalizumab) for the treatment of food allergy.

While omalizumab blocks IgE directly, dupilumab reduces allergic reaction by blocking IgE production by B cells (see figure 4 above). Omalizumab has been approved for asthma, chronic urticaria, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, and for food allergy. Dupilumab has been approved for treatment of eczema, asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, and other diseases.

In COMBINE, we hypothesized that treating multi-food allergic patients with omalizumab and dupilumab together will lead to a better desensitization to food allergens than using only omalizumab or only dupilumab or placebo.

Around 110 participants, ages 4 to 55 years with a history of multiple food allergies have completed the study. Participants were enrolled in one of 3 study arms and the study design is shown in Figure 5, above. Data are currently being analyzed. Learn more about the study here.

Meet the Scientists

Carmela Pablo-Torres Jimenez, PhD

I grew up in Spain. As an infant, I developed eczema (also called atopic dermatitis). Soon after, I also developed allergies to pollen (grasses and olive), house dust mites, and animal dander, which triggered allergic rhinitis and asthma. It significantly affected my quality of life and that of my family, as the itching was painful, my sleep was disrupted, and I often required emergency visits due to respiratory difficulties. I always wondered why I, but not many others, were allergic to pollen and other allergens.

So, when I took an immunology class in college, I was fascinated to learn about immune cells and how they protect the body. I also learnt how they sometimes become hyperactive and attack innocuous substances causing allergic reactions or even attack one’s own’s cells causing autoimmune diseases. My professors Dr. Diaz-Perales and Dr. Blanco were passionate about immunology, and their passion was contagious. I knew then that I wanted a career in immunology.

A few years later, I obtained a PhD in immunology in the research group of Dr. Barber and Dr. Escribese at San Pablo CEU University in Madrid. During my training, I attended Dr. Nadeau lectures at conferences on allergies and asthma and found them fascinating. I applied for a postdoctoral position in her lab at Harvard and was thrilled when I got the position. I have worked in her lab for 1 year now and am constantly learning and discovering.

I am a Senior Research Scientist in Dr. Kari Nadeau’s laboratory in the Department of Environmental Health at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health. I received my Bachelor of Medicine and PhD from the Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University (China), followed by postdoctoral training at the Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California.

Xiaoying Zhou, PhD

I am excited to be a part of Dr. Nadeau’s research team. I am currently working on COMBINE and OUtMATCH food allergy clinical trials, where we are investigating biological drugs and immunotherapy for safe and effective treatments for food allergies. I do that by examining how proteins on immune cells are expressed or altered in allergy and how they are modified with treatment. Understanding these changes can enable us to develop treatments to target key molecules in the allergic pathway.

I enjoy working on food allergy research in Dr. Nadeau’s lab. Dr, Nadeau’s lab has made much progress in treating patients with food allergy and I am excited to understand the molecular mechanisms that are associated with allergic diseases and with desensitization. However, there is still so much that is unknown about immunology and allergic diseases. It is like working on a complex puzzle with many dimensions. I am now working on understanding the mechanisms underlying omalizumab, which has been approved for asthma, food allergies, and other diseases. The drug allows people to consume a higher dose of the food allergen that they are allergic to than they were able to previously. We know it blocks a molecule called IgE, a molecule key to releasing histamine and other inflammatory molecules. We are trying to understand other effects of omalizumab and how it may be used with immunotherapy to make food allergy treatment safer and more effective. I also patented a new target for food allergies with Kari and we will let you know more later.

Yagiz Pat, MD

I am a physician–scientist (MD) trained in medical microbiology and immunology. I study the interactions between the microbiome and allergens. In particular, I use a number of high throughput omic technologies to analyze DNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites. I am also using organoids and organ-on-a-chip systems, which are three-dimensional cell culture models that aim to replicate the structure and function of human organs. These together with other molecular biology techniques can assist us in understanding inflammatory pathways.

The intestinal organoid culture that we use in the Nadeau lab is a state-of-the-art technique which has a high degree of similarity to the human gastrointestinal system. It allows us to study cell responses to environmental factors, including allergens. With this technique, we are planning to investigate how allergens affect the gut barrier and cause inflammation in a patient with food allergies.

Colin Skeen, MS

My name is Colin Skeen, and I am a Research Assistant in Dr. Kari Nadeau’s lab. I am a biomedical engineer with a B.S. from the University of Maryland, College Park and a M.S. from Boston University. As someone with a brother living with severe food allergies, I am excited to join Dr. Nadeau’s lab and work on cutting-edge food allergies research.

I have been working on the Stopping Eczema and Allergy (SEAL) trial, a very exciting Phase II clinical trial. My role is to process participant blood samples, distribute study materials to the clinical sites, and ensure sample collection occurs efficiently and stored correctly so that they can be analyzed. The opportunity to work on a study that aims to prevent food allergies is very exciting!

Recent Publications

- Jiang SY, Cao S, Martinez K, Sharma R, Raeber O, Fernandes A, Bogetic D, Kaushik A, Gupta S, Manohar M, Maeker HT, Chin AR, Long AJ, Feight C, Woch M, Nadeau KC, Chinthrajah RS, Sindher SB. Shrimp oral immunotherapy outcomes in the phase 2 clinical trial: MOTIF. Front Allergy. 2025 Jul 22;6:1458131.

- Zeyneloglu C, Babayev H, Ogulur I, Ardicli S, Pat Y, Yazici D, Zhao B, Chang L, Liu X, D’Avino P, Li M, Biçer C, Kurtoğlu Babayev FH, Dhir R, Nadeau KC, Brüggen MC, Akdis M, Akdis CA. The epithelial barrier theory proposes a comprehensive explanation for the origins of allergic and other chronic noncommunicable diseases. FEBS Lett. 2025 Jul 18.

- Castaño N, Chua K, Nguyen A, Marshall W, Hofmann GH, Lee J, Tsai M, Sindher SB, Nadeau KC, Chinthrajah RS, Galli SJ, Tang SKY. A hand-operated microfluidic sample preparation-to-analysis workflow for simplifying the basophil activation test. Lab Chip. 2025 Jul 23;25(15):3779-3791.

- Hund SK, Sampath V, Zhou X, Thai B, Desai K, Nadeau KC. Scientific developments in understanding food allergy prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Front Immunol. 2025 Apr 22;16:1572283.

- Chinthrajah RS, Sindher SB, Nadeau KC, Leflein JG, Spergel JM, Petroni DH, Jones SM, Casale TB, Wang J, Carr WW, Shreffler WG, Wood RA, Wambre E, Liu J, Akinlade B, Atanasio A, Orengo JM, Hamilton JD, Kamal MA, Hooper AT, Patel K, Laws E, Mannent LP, Adelman DC, Ratnayake A, Radin AR. Dupilumab as an Adjunct to Oral Immunotherapy in Pediatric Patients With Peanut Allergy. Allergy. 2025 Mar;80(3):827-842.

- Zhou X, Dunham D, Sindher SB, Long A, Fernandes A, Chang I, Assa’ad A, Pongracic J, Spergel JM, Tam J, Tilles S, Wang J, Boyd SD, Chinthrajah RS, Nadeau KC. HLA-DR+ regulatory T cells and IL-10 are associated with success or failure of desensitization outcomes. Allergy. 2025 Mar;80(3):762-774.

- Stephen-Victor E, Kuziel GA, Martinez-Blanco M, Jugder BE, Benamar M, Wang Z, Chen Q, Lozano GL, Abdel-Gadir A, Cui Y, Fong J, Saint-Denis E, Chang I, Nadeau KC, Phipatanakul W, Zhang A, Farraj FA, Holder-Niles F, Zeve D, Breault DT, Schmitz-Abe K, Rachid R, Crestani E, Rakoff-Nahoum S, Chatila TA. RELMβ sets the threshold for microbiome-dependent oral tolerance. Nature. 2025 Feb;638(8051):760-768.

- Arnau-Soler A, Tremblay BL, Sun Y, Madore AM, Simard M, Kersten ETG, Ghauri A, Marenholz I, Eiwegger T, Simons E, Chan ES, Nadeau K, Sampath V, Mazer BD, Elliott S, Hampson C, Soller L, Sandford A, Begin P, Hui J, Wilken BF, Gerdts J, Bourkas A, Ellis AK, Vasileva D, Clarke A, Eslami A, Ben-Shoshan M, Martino D, Daley D, Koppelman GH, Laprise C, Lee YA, Asai Y. Food Allergy Genetics and Epigenetics: A Review of Genome-Wide Association Studies. Allergy. 2025 Jan;80(1):106-131.

- Sindher SB, Nadeau KC, Chinthrajah RS, Leflein JG, Bégin P, Ohayon JA, Ponda P, Wambre E, Liu J, Khokhar FA, Akinlade B, Maloney J, Orengo JM, Hamilton JD, Kamal MA, Hooper AT, Patel N, Patel K, Laws E, Mannent LP, Radin AR. Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab in Children With Peanut Allergy: A Multicenter, Open-Label, Phase II Study. Allergy. 2025 Jan;80(1):227-237.

- Satitsuksanoa P, van de Veen W, Tan G, Lopez JF, Wirz O, Jansen K, Sokolowska M, Mirer D, Globinska A, Boonpiyathad T, Schneider SR, Barletta E, Spits H, Chang I, Babayev H, Tahralı İ, Deniz G, Yücel EÖ, Kıykım A, Boyd SD, Akdis CA, Nadeau K, Akdis M. Allergen-specific B cell responses in oral immunotherapy-induced desensitization, remission, and natural outgrowth in cow’s milk allergy. Allergy. 2025 Jan;80(1):161-180.

- Seastedt H, Han X, Fernandes A, Galli SJ, Boyd SD, Nadeau KC, Manohar M, Chinthrajah S. Association of cytotoxic effector memory CD8+T cells with sustained unresponsiveness after peanut oral immunotherapy. Allergy. 2025 Jan;80(1):319-322.

- Sun N, Ogulur I, Mitamura Y, Yazici D, Pat Y, Bu X, Li M, Zhu X, Babayev H, Ardicli S, Ardicli O, D’Avino P, Kiykim A, Sokolowska M, van de Veen W, Weidmann L, Akdis D, Ozdemir BG, Brüggen MC, Biedermann L, Straumann A, Kreienbühl A, Guttman-Yassky E, Santos AF, Del Giacco S, Traidl-Hoffmann C, Jackson DJ, Wang DY, Lauerma A, Breiteneder H, Zhang L, O’Mahony L, Pfaar O, O’Hehir R, Eiwegger T, Fokkens WJ, Cabanillas B, Ozdemir C, Kistler W, Bayik M, Nadeau KC, Torres MJ, Akdis M, Jutel M, Agache I, Akdis CA. The epithelial barrier theory and its associated diseases. Allergy. 2024 Dec;79(12):3192-3237.

- Zhou X, Simonin EM, Jung YS, Galli SJ, Nadeau KC. Role of allergen immunotherapy and biologics in allergic diseases. Curr Opin Immunol. 2024 Dec;91:102494.

- Marques-Mejias A, Bartha I, Ciaccio CE, Chinthrajah RS, Chan S, Hershey GKK, Hui-Beckman JW, Kost L, Lack G, Layhadi JA, Leung DYM, Marshall HF, Nadeau KC, Radulovic S, Rajcoomar R, Shamji MH, Sindher S, Brough HA. Skin as the target for allergy prevention and treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024 Aug;133(2):133-143.

- Nakonechna A, van Bergen A, Anantharachagan A, Arnold D, Johnston N, Nadeau K, Rutkowski K, Sindher SB, Sriaroon P, Thomas I, Vijayadurai P, Wagner A, Davis CM. Fish and shellfish allergy: Presentation and management differences in the UK and US-analysis of 945 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Glob. 2024 Jul 22;3(4):100309.

- Hong X, Nadeau K, Wang G, Larman B, Smith KN, Pearson C, Ji H, Frischmeyer-Guerrerio P, Liang L, Hu FB, Wang X. Metabolomic profiles during early childhood and risk of food allergies and asthma in multiethnic children from a prospective birth cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024 Jul;154(1):168-178.

- Barshow S, Tirumalasetty J, Sampath V, Zhou X, Seastedt H, Schuetz J, Nadeau K. The Immunobiology and Treatment of Food Allergy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2024 Jun;42(1):401-425.

- Tang SKY, Castaño N, Nadeau KC, Galli SJ. Can artificial intelligence (AI) replace oral food challenge? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024 Mar;153(3):666-668.

- Voskamp AL, Khosa S, Phan T, DeBerg HA, Bingham J, Hew M, Smith W, Abramovitch J, Rolland JM, Moyle M, Nadeau KC, Lack G, Larché M, Wambre E, O’Hehir RE, Hickey P, Prickett SR. Phase 1 trial supports safety and mechanism of action of peptide immunotherapy for peanut allergy. Allergy. 2024 Feb;79(2):485-498.

- Castaño N, Chua K, Kaushik A, Kim S, Cordts SC, Nafarzadegan CD, Hofmann GH, Seastedt H, Schuetz JP, Dunham D, Parsons ES, Tsai M, Cao S, Desai M, Sindher SB, Chinthrajah RS, Galli SJ, Nadeau KC, Tang SKY. Combining avidin with CD63 improves basophil activation test accuracy in classifying peanut allergy. Allergy. 2024 Feb;79(2):445-455.

- Croote D, Wong JJW, Pecalvel C, Leveque E, Casanovas N, Kamphuis JBJ, Creeks P, Romero J, Sohail S, Bedinger D, Nadeau KC, Chinthrajah RS, Reber LL, Lowman HB. Widespread monoclonal IgE antibody convergence to an immunodominant, proanaphylactic Ara h 2 epitope in peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024 Jan;153(1):182-192.e7.

- Balz K, Kaushik A, Cemic F, Sampath V, Heger V, Renz H, Nadeau K, Skevaki C. Cross-reactive MHC class I T cell epitopes may dictate heterologous immune responses between respiratory viruses and food allergens. Sci Rep. 2023 Sep 8;13(1):14874.

- Lee AS, Parsons ES, Chang I, Dunham D, Chinthrajah RS, Nadeau KC. Quantitative analysis of urinary cytokines in food-allergic and healthy individuals. Allergy. 2023 Sep;78(9):2523-2526.

- Tirumalasetty J, Barshow S, Kost L, Morales L, Sharma R, Lazarte C, Nadeau KC. Peanut allergy: risk factors, immune mechanisms, and best practices for oral immunotherapy success. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2023 Jul-Dec;19(7):785-795.

- Ciliberti A, Zaslavsky J, Morcott T, Bozen A, Samady W, Lombard L, Nimmagadda S, Nadeau K, Gupta R, Tobin M. Evaluating the Food Allergy Passport: A Novel Food Allergy Clinical Support Tool. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023 Apr;11(4):1162-1168.e7.

- Sindher SB, Barshow S, Tirumalasetty J, Arasi S, Atkins D, Bauer M, Bégin P, Collins MH, Deschildre A, Doyle AD, Fiocchi A, Furuta GT, Garcia-Lloret M, Mennini M, Rothenberg ME, Spergel JM, Wang J, Wood RA, Wright BL, Zuberbier T, Chin AR, Long A, Nadeau KC, Chinthrajah RS. The role of biologics in pediatric food allergy and eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023 Mar;151(3):595-606.

- Sindher SB, Chin AR, Aghaeepour N, Prince L, Maecker H, Shaw GM, Stevenson DK, Nadeau KC, Snyder M, Khatri P, Boyd SD, Winn VD, Angst MS, Chinthrajah RS. Advances and potential of omics studies for understanding the development of food allergy. Front Allergy. 2023 Mar 24;4:1149008.

- Stankovich GA, Warren CM, Gupta R, Sindher SB, Chinthrajah RS, Nadeau KC. Food allergy risks and dining industry – an assessment and a path forward. Front Allergy. 2023 Mar 29;4:1060932.

- Akdis CA, Akdis M, Boyd SD, Sampath V, Galli SJ, Nadeau KC. Allergy: Mechanistic insights into new methods of prevention and therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2023 Jan 18;15(679):eadd2563.

- Liu EG, Zhang B, Martin V, Anthonypillai J, Kraft M, Grishin A, Grishina G, Catanzaro JR, Chinthrajah S, Sindher T, Manohar M, Quake AZ, Nadeau K, Burks AW, Kim EH, Kulis MD, Henning AK, Jones SM, Leung DYM, Sicherer SH, Wood RA, Yuan Q, Shreffler W, Sampson H, Shabanova V, Eisenbarth SC. Food-specific immunoglobulin A does not correlate with natural tolerance to peanut or egg allergens. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Nov 16;14(671):eabq0599.

- Zhou X, Yu W, Dunham DM, Schuetz JP, Blish CA, DeKruyff RH, Nadeau KC. Cytometric analysis reveals an association between allergen-responsive natural killer cells and human peanut allergy. J Clin Invest. 2022 Oct 17;132(20):e157962.

- Sindher SB, Long A, Chin AR, Hy A, Sampath V, Nadeau KC, Chinthrajah RS. Food allergy, mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment: Innovation through a multi-targeted approach. Allergy. 2022 Oct;77(10):2937-2948.

- Warren C, Sherr J, Sindher S, Nadeau KC, Casale TB, Ward D, Gupta R, Chinthrajah RS. The impact of COVID-19 on a national sample of US adults with food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022 Oct;10(10):2744-2747.

Last Updated

In home exposures linked to increased ER visits for asthma

A new study published yesterday in JAMA Network Open by researchers from the Department of Environmental Health examined reports from tenants in housing across Boston, and found that reports of mold, rodents, and other indoor environmental exposures were associated with higher rates of emergency room visits for asthma-related illnesses.

“The link between healthy housing and asthma has been well established for many years,” explains Zichuan Li, MSc, doctoral student at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and a co-author of the study. “However, its role in driving disparities by race and class has received less attention, and systematically assessing indoor exposures at high spatial resolution across large areas has proven difficult, because of the private nature of the home environment. This study is a substantial step forward in establishing the association between uneven access to healthy housing and asthma disparities.”

In 2023, the Boston Public Health Commission’s report on asthma found that the annual rate of asthma ED visits for Black residents and Latino residents is respectively 9.0-fold and 4.4-fold higher than for White residents, with similar effects for low-income Boston residents.

The study authors note that while housing conditions are a strong contributor to asthma disparities by race, they do not fully explain them. “There are many other ways in which social inequality and structural racism can predispose people to asthma risk, including psychosocial stress, barriers to care, and mistreatment within the health care system,” explains Adam Haber, PhD, Associate Professor of Environmental Health, and co-author of the paper. “But, facilitating access to healthy housing conditions, either by moving, or through repairs—particularly substantive structural upgrades or improvements to reduce inadequate ventilation, dampness and mold, and exposure to pests—not only remediates allergen risks but can also improve psychosocial stressors that contribute to worse asthma outcomes.”

Read the full article in JAMA here.

Li Z, Carryl SS, Samuels EA, Foer D, Haber AL. Tenant Reports of In-Home Asthma Triggers and Adult Emergency Department Use. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(10):e2537874. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.37874

Last Updated

Green AI: Hype or Hope?

Last Updated

Featured in this article

Are current lead limits strict enough to keep children safe?

A new commentary suggests that the safety threshold for lead in soil should be reduced in order to better protect young children, and more testing is needed on fire-affected homes in LA area

For Immediate Release:

Urban wildfires in Los Angeles have highlighted the increased risk of soil lead exposure, especially for young children, and the current approach to mitigating this risk in L.A. does not accurately reflect the current understanding of risks to children from lead, according to a new commentary published today in Nature from researchers at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University.

The LA fires in January 2025 devastated neighborhoods and left potential environmental hazards on burn sites as well as unaffected homes. “Urban fires burned through structures and materials containing lead, such as paint and plumbing, as well as arsenic and other toxic metals,” write the authors. “While the immediate aftermath of wildfires understandably centers on loss of life and property, environmental health threats posed by legacy contaminants in soil can persist for years after flames are extinguished.”

Air quality monitors in the LA area revealed an alarming 110-fold increase in atmospheric lead levels immediately after the fires, and soil testing later confirmed elevated lead levels in areas downwind of the Eaton fire. This poses a long-term risk of exposure, particularly for biologically sensitive populations like young children, through contact with contaminated soil or inhalation of lead dust.

”Young children’s developing biological systems are highly sensitive to influences from their developmental environment, and lead exposure at a young age poses a risk to all of these systems, particularly for brain and cognitive development,” says Lindsey Burghardt, co-author of the commentary and Chief Science Officer at the Center for the Developing Child at Harvard University. “It is critical that we implement actionable solutions to protect young children from lead exposure after a wildfire, which will have positive impacts for their health and well-being across the lifespan.”

The commentary is recommending two critical reforms:

- Soil testing (specifically “post-clearance confirmatory” testing) should be required after wildfire cleanup, as has been done for every major wildfire in California since 2007.

- The California’s residential Preliminary Remediation Goal (PRG) — the target threshold that residential soil should meet in order to be considered safe — for lead in soil should be lowered from 80 mg/kg to 55 mg/kg to reflect updated science and health-protective standards.

“People all want to know the same thing, ‘Is it safe?’ The current policy was falling behind the science when it came to addressing lead in soil after the fires,” said Joseph Allen, co-author of the commentary, and Professor of Exposure Assessment Science at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “There are some basic steps people can take to help reduce their exposure: wash hands, don’t track in soil into your home, keep surfaces clean, upgrade indoor air filtration and use portable air cleaners.”

Drs. Allen and Burghardt, as well as the rest of the Commentary authors, are all a part of the LA Fire HEALTH Study Consortium. The LA Fire HEALTH Study was started in response to the need for answers in the wake of the LA fires. In an unprecedented collective scientific effort to understand the short- and long-term health impacts of wildfires, researchers from Cedars-Sinai; Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; the Keck School of Medicine of USC; Stanford; University of California, Davis; University of California, Irvine; University of California, Los Angeles (David Geffen School of Medicine, Fielding School of Public Health, UCLA Health); University of Texas at Austin; and Yale have launched a 10-year study of LA fires.

“Our collaborative work with the LA HEALTH consortium is unprecedented and this lead finding is one example of how scientific research can help the public in real time to protect and help the community,” said Kari Nadeau, co-author of the commentary, and Chair of the Department of Environmental Health at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Read the full Commentary: Allen, Azimi, Pei, Ferguson, Burghardt, Nadeau. “Post-Fire Soil Hazards: Recommendations for Updated Soil Testing Protocols and Clearance Thresholds.” Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology. August 8, 2025 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-025-00796-w

Read a Fact Sheet about the Recommendations here.

Media Contacts:

Carly Stearnbourne, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

cstearnbourne@hsph.harvard.edu, 617-571-2268

Rebecca Hansen, Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University

rebecca_hansen@harvard.edu, 617-320-2883

Last Updated

A new article published Tuesday in Nature Cities finds that heat stress is responsible for productivity losses between 29.0% to 41.3% on construction job sites. As demand for new construction grows, and extreme heat affects cities across the globe, understanding the effects of heat and humidity on outdoor workers is key to protecting both worker health, as well as project timelines and costs.

“If unmitigated, heat can lead to acute fatal outcomes (for example, heat stroke), long-term health effects or increase the risk of workplace injuries,” the study authors write. “However, even before reaching dangerous levels, physically demanding work in hot-humid conditions is associated with discomfort, irritability, loss of concentration and fatigue.”

For businesses and employers, there is mounting evidence that shows that heat exposure leads to significant reductions in worker productivity, resulting in longer project timelines, development delays and, subsequently, substantial economic losses.

“The conditions for construction workers can actually be a lot worse than other occupational settings, because — in addition to working outside in the elements — constructions workers often use heat-generating tools as part of the job, such as welding torches, power tools, etc. In addition, heat reflects off of concrete structures and steel, making it even hotter for the workers,” says Barrak Alahmad, study co-author, and researcher at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “To account for those scenarios, we measured the exact temperatures and humidity and conditions for workers at an individual level; each worker wore a small sensor around their waist that continuously, minute by minute, collected the data.”

Research like this highlights the cost of doing nothing to mitigate heat stress among workers, and lays the groundwork for future research to investigate what types of strategies can protect workers while also boosting productivity and reducing costs for construction companies and builders.

There are workers that are doing a lot of strenuous and difficult jobs in the hot weather,” says Dr. Alahmad. “And right now, globally, there is lack of protection for these workers.

This research also comes at a time when OSHA is in the middle of the regulatory process to establish a federal heat rule. Right now in the US, there is no federal heat rule, heat is instead governed by the general duty clause. “Creating a federal heat rule would mean that OSHA could regulate things like rest, water, and shade, and also improve planning for construction companies to try to mitigate the effects of heat ,” says Dr. Alahmad.

This is important not only to protect workers, but also to protect the bottom line for construction projects, where loss of productivity leads to delays, missed deadlines, and cost overruns.

The research was conducted in Taiwan where a growing demand for housing has led to a construction boom in the hot, humid climate. Co-author Shih-Chun Candice Lung from the Research Center for Environmental Changes at Academia Sinica in Taipei, Taiwan, collaborated with Dr. Alahmad on the findings. Dr. Lung is an alumnus of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who previously studied under Dr. Jack Spengler.

This investigation was made possible by grant no. T42 OH008416 from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) through Harvard–NIOSH Education and Research Center (ERC) grant. In addition, this research was supported by the Institute of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health, Ministry of Labor, Executive Yuan, Taiwan, under project nos. 1050004 and 1060047.

Last Updated

Featured in this article

A new study clarifies the importance of nature for mental health in urban settings and provides low-cost recommendations for improving public health in cities.

As the proportion of the global population living in cities rises to 70% by 2050, mental health challenges more common in urbanites — such as anxiety and mood disorders — become even more broadly relevant. A new study from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Natural Capital Project (NatCap) at Stanford University shows that spending even a little time in nature provides significant benefits for a broad range of mental health conditions. The results, published today in Nature Cities, offer guidance to urban planners, policymakers, and others for how to use greenspace as a mental health solution, one that comes with additional benefits like lowering temperatures and sequestering carbon. The research team is now incorporating its findings into a modeling tool for urban planners.

“We are working to translate what we found through this analysis to create more intuitive indicators that would be useful for decision-makers,” said Yingjie Li, postdoctoral scholar at NatCap and lead author of the study. “For example, if a city currently has 20% green space or tree cover, we can try to predict how many preventable cases of mental health disorders could be avoided if that were increased to 30%. Our software will also estimate the potential reduction in healthcare costs associated with such improvements in urban nature.”

NatCap’s flagship mapping and modeling tools, known as InVEST, are used around the world to quantify ecosystem services, or nature’s benefits to people. For years the team has been building a collection of tools focused specifically on nature in cities.

“I was excited to be part of this work with the Stanford team. This study fills a critical gap in our ability to examine different types of nature to improve mental health outcomes. InVEST is an innovative and impactful solutions-based tool that will shape how we plan for people to enjoy healthier lives in a healthier planet” said Kari Nadeau, John Rock Professor of Climate and Population Studies, and Chair of the Department of Environmental Health at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The team’s analysis collates data from close to 5,900 participants across 78 field-based experimental studies, all either randomized controlled trials or pre-post intervention studies. While all types of urban nature provided benefits, the researchers found urban forests were even better for certain measures like reducing depression and anxiety. Young adults experience even greater benefits than the general population — an important data point because most mental health disorders emerge before the age of 25. Perhaps surprisingly, spending non-active, stationary time in greenspaces was more effective at reducing negative mental health outcomes like depression than active time in nature, though both are equally beneficial for positive outcomes like vitality (measured by asking how alive, alert, and energized people feel). They also found effects to be greater in Asian countries, where physiological effects may be enhanced by cultural associations with nature that “prime” people to their benefits.

Based on the findings of this analysis, while larger city parks and forests are critical, the researchers suggest it is also important to create smaller “pocket parks” and additional street trees to increase access throughout cities. Even additional windows with views facing green spaces could be beneficial, as well as quiet, nature-filled spaces and community programming that provides passive nature exposure such as guided park meditation — relatively low-cost methods for improving public health in cities.

At the personal level, Li has found that doing this work has improved his own lifestyle. He walks to the office more frequently and finds he is more curious about birds and plants he encounters along the way. “I also talk to my friends about thinking this way and encourage them to notice how even small moments with nature can make a difference. This work has helped me see that urban nature isn’t just good for cities, it’s good for us.” said Li.

Li is a postdoctoral scholar in the Department of Biology in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences (H&S). Nadeau is Chair of the Department of Environmental Health and Professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Harvard Medical School. Additional co-authors on the paper are: Lisa Mandle (NatCap/Woods Institute), Anders Rydström (NatCap/Biology, H&S), Tong Wu (NatCap/Woods Institute), Yougeng Lu (NatCap/Biology, H&S), and Gretchen Daily (NatCap/Biology, H&S and Woods Institute; Yuanyuan Mao and Roy P. Remme from the Institute of Environmental Sciences at Leiden University; Xin Lan from the Department of Geography, Environment, and Spatial Sciences at Michigan State University; Chao Song from the College of Ecology at Lanzhou University;; and Andreas Meyer-Lindenberg from the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Central Institute of Mental Health and Medical Faculty Mannheim/University of Heidelberg.

This research is supported by grants from the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment’s Realizing Environmental Innovation Program, the Cyrus Tang Foundation, the Marcus and Marianne Wallenberg Foundation, the Heinz Foundation, the Winslow Foundation, and individual contributors John Miller and Kristy Hsiao.

Media contacts:

Elana Kimbrell, elanak@stanford.edu

Carly Stearnbourne, cstearnbourne@hsph.harvard.edu

Last Updated

Featured in this article

Teens come together from across globe to learn about climate, equity, and health

Earlier this month, Harvard Chan C-CHANGE and Putney Student Travel hosted 50 high school students at the Harvard Chan campus for the fifth annual Youth Summit on Climate, Equity, and Health.

The summit brought together a diverse group of students, with representation from ten states as well as students from China, Singapore, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom. Over the last five years, we have welcomed 435 students from 35 different states and 14 countries.

Students heard presentations from C-CHANGE director and deputy director Mary Rice and Amruta Nori-Sarma, as well as core faculty members, Vanessa Kerry, Gaurab Basu, and Lindsey Burghardt. Additional Harvard affiliates included K. “Vish” Viswanath, Sappho Gilbert, Barrak Alahmad, and Harvard iLab’s Rebekah Emmanuel and Virginia Canestraight of SEAS. Students also heard from policymakers such as Catherine McCandless from the City of Boston, Jeffrey Sanchez and entrepreneurs like Kip Pastor, and industry experts like Phil Dahlin of J&J.

Throughout the week, they learned how to take their passion for climate solutions and turn it into action, formed lasting relationships, and came away with a better understanding of how to make an impact in their own communities. Learn more on the Youth Summit website.