Understanding the Structural Roots of Nepal’s Gen Z Movement

Part 1 of this series examined the September 2025 protest events of Nepal in the days leading up to and during the violence itself. This section shifts focus to ask what made those days possible. Why were tens of thousands of young Nepalis willing to risk confrontation with security forces? What had shifted in Nepal’s political and economic landscape to make this level of mobilization feasible? For atrocity prevention practitioners, this case study on Nepal serves to demonstrate why structural risk assessment must extend beyond monitoring immediate conflict indicators, and why understanding how these vulnerabilities interact and compound over time matters significantly for early warning frameworks.

Nepal’s Labor Market

Nepal’s labor force is predominantly informal and agriculture-based. Nearly three-fifths of the economically active population is engaged in agriculture, even though agriculture contributes only around 25% of GDP. Post-COVID, the government and donors have advocated for modernizing agriculture (e.g. agro-processing, commercialization) to improve productivity and youth appeal.

Nepal’s industrial sector (including manufacturing, construction, utilities, mining) employs roughly 15% of workers. Construction is a major employer, accounting for about 14% of employment (nearly 1 million jobs in 2018).

The services sector in Nepal employs about 20–22% of the workforce, but generated over 60% of GDP in the fiscal year 2024/25. Notably, tourism and hospitality is a significant sub-sector: just before COVID, tourism directly employed about 371,000 people (11.5% of total employment), making it the fourth-largest industry by employment.

Nepal’s digital economy is an emerging sector that has shown promise, particularly for urban youth. Currently, information and communication services employ less than 1% of workers (around 60,000 people as of 2018). This sector grew during and after the pandemic as businesses and education went online. The business process outsourcing (BPO) industry – such as call centers, IT support, and software services – is expanding rapidly.

Nepal has a low-cost, English-speaking workforce, and even though the BPO/IT sector is small relative to the labor force, it is regarded as a “fast-emerging sector” with increasing demand for tech skills. The government and development partners identify digital services and ICT as a high-growth area for job creation. In fact, the World Bank’s 2025 strategy for Nepal highlights digital jobs (e.g. IT services, digital finance) as a priority for absorbing educated youth.

The Unemployment Trap

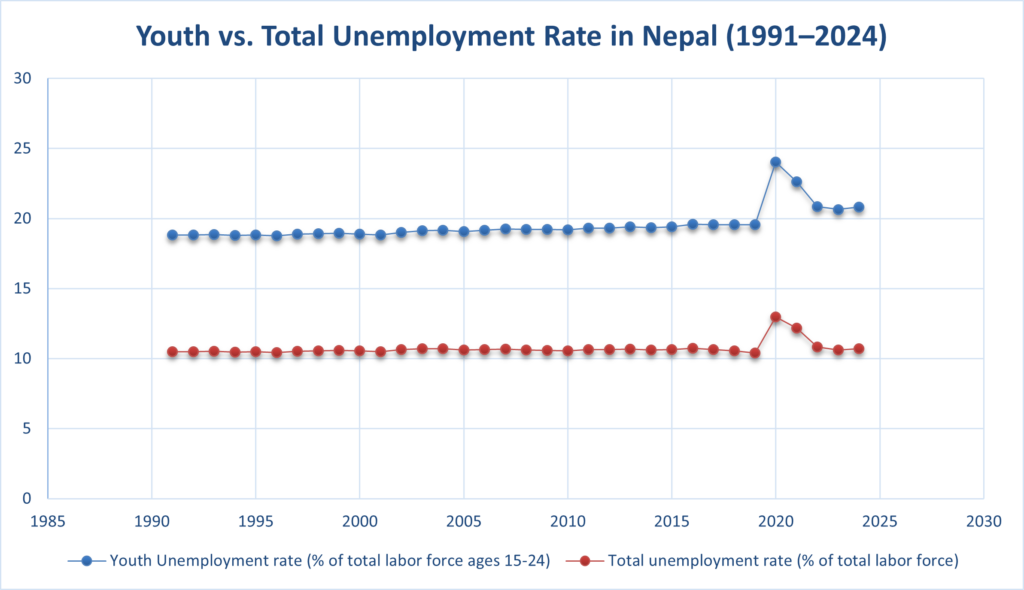

Nepal has one of the youngest populations in South Asia. Approximately 56% of its 30 million citizens are under the age of 30. Yet, the country’s labor market has been structurally incapable of absorbing its own young workforce, leaving an entire generation trapped between educational aspiration and economic exclusion.

Youth unemployment reached 20.82% in 2024, more than double the overall unemployment rate of 10.71%. Over the past three decades, youth unemployment has consistently hovered around twice the national average. A large share of youth work in family farms or informal jobs that are not officially counted. The NEET rate (youth neither in employment, education or training) is among the highest in South Asia, especially for young women.

On the bright side, the government’s investments in roads and energy have translated into thousands of construction jobs, though many are temporary. The manufacturing sector, while small, has seen pockets of growth (e.g. in food processing and construction materials) that need young factory workers and technicians. Additionally, telecommunications and retail (such as mobile phone services, shopping centers) grew as consumers turned to e-commerce and delivery services during the pandemic, which opened new roles for youth in delivery, sales, and customer service.

Remittance Dependency

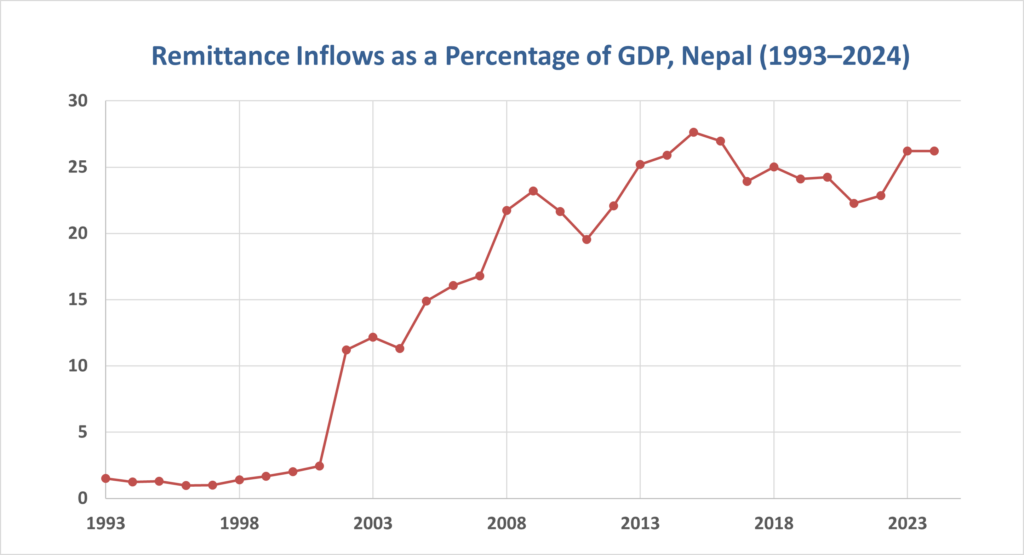

Over the past two decades, Nepal’s reliance on remittances has deepened significantly. In 2024, remittance inflows reached approximately 26% of GDP, positioning Nepal among the nations with the highest remittance-to-GDP ratios globally. Totaling over $11 billion annually, these funds serve as the country’s primary source of foreign exchange and provide essential financial support to millions of households. The World Bank’s post- Gen Z revolution Development Update estimates that without the inflow of remittances, an additional 2.6 million people would fall below the poverty line.

About 14% of the population work abroad, primarily in Gulf states (Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates), Malaysia, India, South Korea, and Japan. At the national level, remittances support the balance of payments and shore up foreign exchange reserves, preventing a currency crisis.

Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) & Political Instability

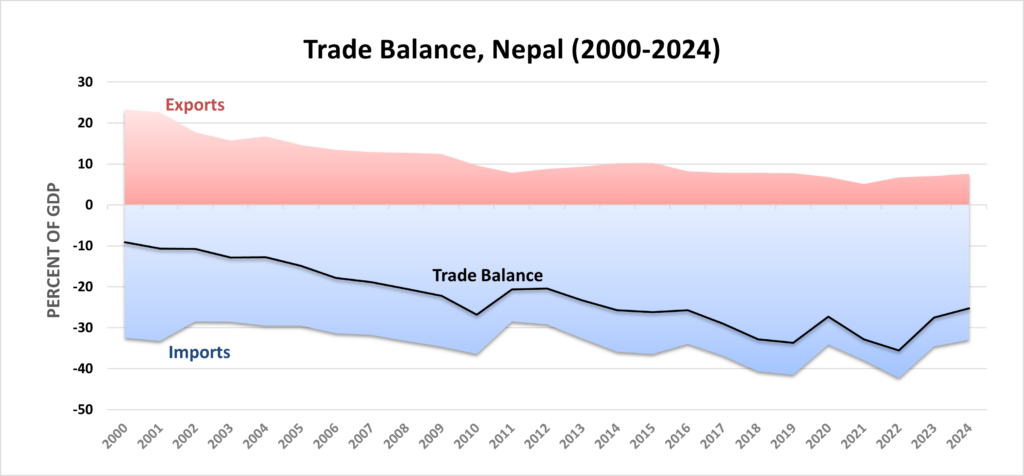

The persistent imbalance in Nepal’s external trade remains one of the most salient indicators of its economic vulnerability. Despite exports experiencing remarkable growth of 58 percent year-on-year in the first five months of fiscal year 2025/26, they represented merely 13 percent of total trade.

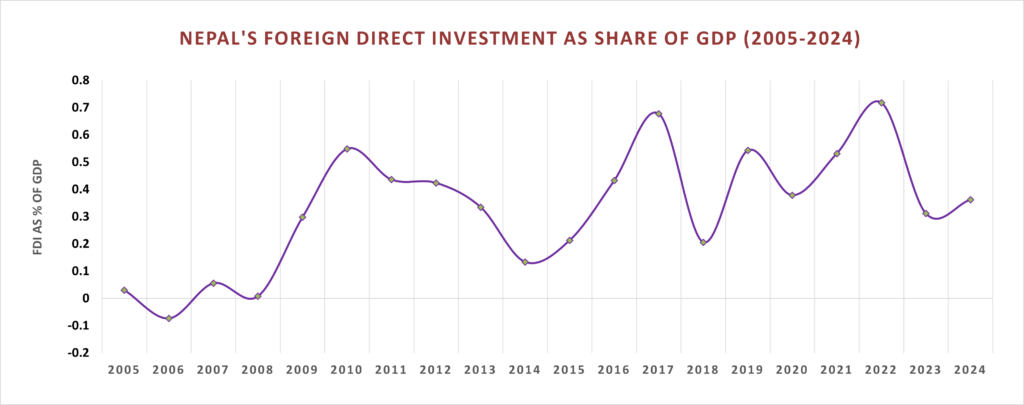

In the last fiscal year, pledged FDI amounted to approximately $489 million, while net inflows reached only about $90 million, indicating that less than one-fifth of committed investment materialised. Analysts and former officials at the Central Bank of Nepal identify procedural delays, licensing and pre-approval requirements, weak regulatory coordination, corruption, and political instability as key deterrents to investment execution.

Since Nepal abolished its monarchy and became a federal democratic republic in 2008, power has frequently alternated among a small group of prominent leaders from the three largest parties: K.P. Sharma Oli (CPN-UML), Sher Bahadur Deuba (Nepali Congress), and Pushpa Kamal Dahal (‘Prachanda’). Critics and, increasingly, ordinary citizens see this as a political class that treats governance as a game of musical chairs, where power is rotated among the same faces with little regard for the aspirations or welfare of the population.

Rural Neglect and Disaster Vulnerability

Nepal’s underinvestment in rural infrastructure and disaster preparedness has left millions of citizens dangerously vulnerable to natural hazards. In 2024 and 2025 alone, Nepal experienced a series of catastrophic disasters. On July 12, 2024, two buses with 65 passengers were swept into the Trishuli River by a landslide on the Madan Ashrit Highway. In September of the same year, severe flooding and landslides across more than 50 districts including Kavrepalanchok, Sindhuli, and Lalitpur resulted in 224 deaths and extensive destruction. More recently, in October of 2025, heavy rainfall triggered landslides and flooding in Ilam district, killing at least 44 people and leaving several missing.

Despite these recurring disasters, the government has made efforts to strengthen disaster management. With support from international donors and NGOs, Nepal enacted the Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2017, which established a multi-tier institutional structure to coordinate disaster response across federal, provincial, and local governments. Following the devastating 2015 earthquake, Nepal updated building codes and strengthened their enforcement in affected districts. However, the continued scale of casualties and destruction suggests that implementation gaps, inadequate funding, and insufficient rural infrastructure investment continue to undermine these disaster preparedness efforts.

Nepal’s Digital Economy and Social Media Influence

Social media did not cause Nepal’s 2025 crisis, but it fundamentally reshaped how grievances were articulated, amplified, and acted upon.

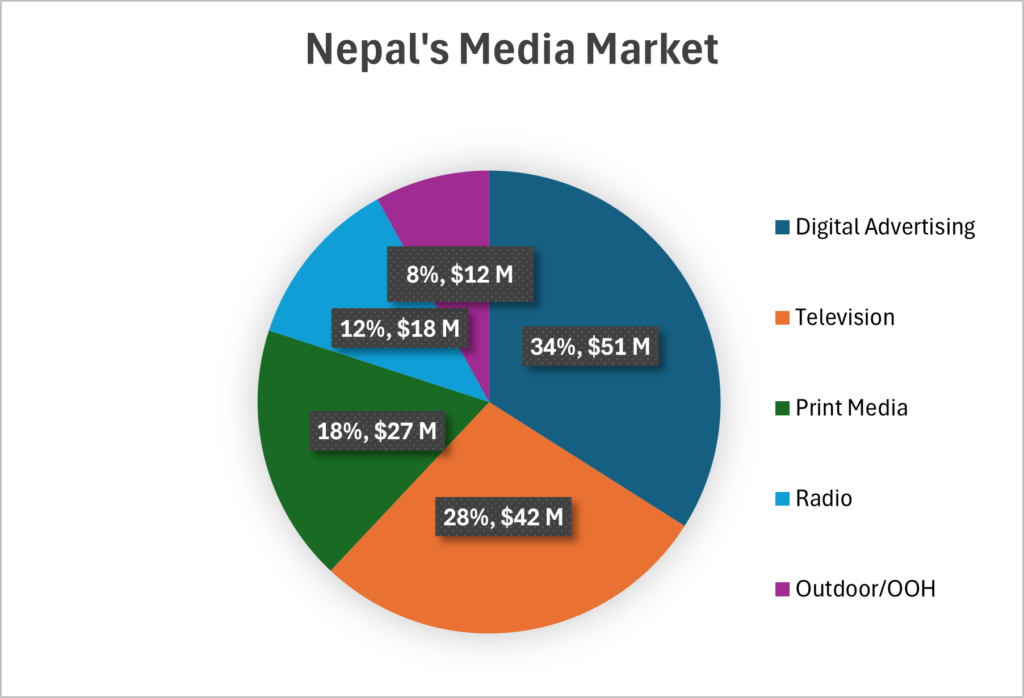

Over the past five years, Nepal has experienced a significant expansion in digital connectivity. By early 2025, internet penetration had reached 56 percent, with 16.5 million individuals using the internet. Social media adoption has also expanded rapidly, with 14 million active social media user identities recorded in January 2025 equivalent to 48 percent of the total population. These trends point to a markedly more connected and digitally mediated social environment than in previous years. Content creation, digital entrepreneurship, freelancing, and online businesses have become viable pathways to income, particularly for urban youth with digital literacy and reliable internet access. Digital advertising now commands 34% market share, surpassing television (28%), print media (18%), radio (12%), and outdoor advertising (8%). The dominance of digital advertising is driven by increased internet and smartphone use, the effectiveness of social media campaigns, and the growing influence of the creator economy.

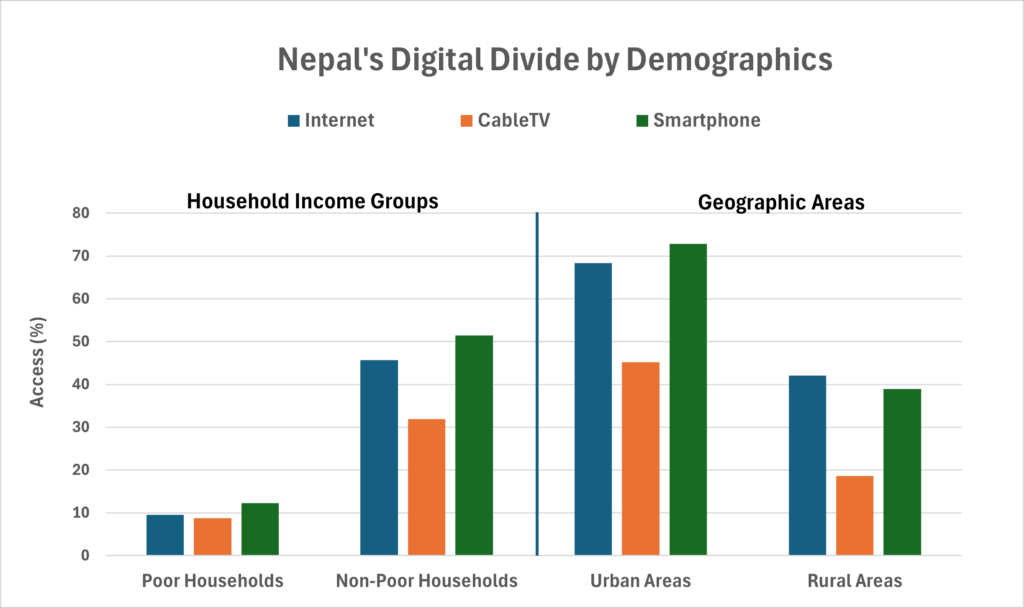

However, this digital growth is unevenly distributed. Internet access varies dramatically by economic status: only 9.5% of those living in poverty have internet access. Similarly, cable TV access is 9% for poor households versus 32% for non-poor households. Geographic disparities are equally pronounced: while 79% of households in Kathmandu Valley have internet access, this drops to 43% in other urban areas and just 17% in rural regions.

Social media did not cause Nepal’s 2025 crisis, but it fundamentally reshaped how grievances were articulated, amplified, and acted upon. The convergence of widespread smartphone adoption, algorithmic amplification, and a politically frustrated youth population created the conditions for a digitally mediated uprising that ultimately forced a transition in the country’s political leadership. The 2025 protests were largely led by youth in urban areas who had reliable internet access, digital literacy, and the ability to navigate platforms like TikTok, Instagram, Reddit, and Discord. Rural populations, by contrast, were less digitally connected and less able to participate in online coordination efforts. This does not mean rural grievances were any less severe, but it does demonstrate that the movement’s digital infrastructure was concentrated in cities, particularly Kathmandu.

Nepal’s Gen Z protests cannot be understood as a sudden phenomenon driven by social media alone, nor as a purely economic revolt. Rather, it emerged from the cumulative interaction of long-standing vulnerabilities that compounded over time and narrowed peaceful channels for political expression. For early warning and atrocity prevention frameworks, Nepal’s case study highlights the need to move beyond event-driven indicators and toward deeper assessments of how stressors interact to transform latent discontent into mass mobilization.

Part 3 of this series turns from diagnosis to the use of early warning/early action technologies. It explores the emerging ecosystem of geospatial early-warning tools, conflict forecasting models and mapping platforms that can be used by governments, civil society organizations, and international actors in atrocity prevention. Drawing on the applied work of the Atrocity Prevention Lab, it asks how spatial data, risk models, and community-generated information can be translated into timely early action rather than reaction.