Understanding the links between climate, food systems, and global diets

Worsening climate trends—including rising temperatures, ocean acidification, and deforestation—are not just causing more extreme weather events, they’re impacting humanity’s ability to produce adequate supplies of nutritious food, Jessica Fanzo recently told a Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health audience.

Much of this is due to human activity, she said. “We have a huge footprint on the planet. We’re demanding energy, food, water, paper. We’re growing in our population sites. We are flying around the world, and all of this is having huge ramifications on the ability for earth to function in a sustainable way.” But she urged the students in the audience not to give up, and to keep working to improve the health of people and the planet.

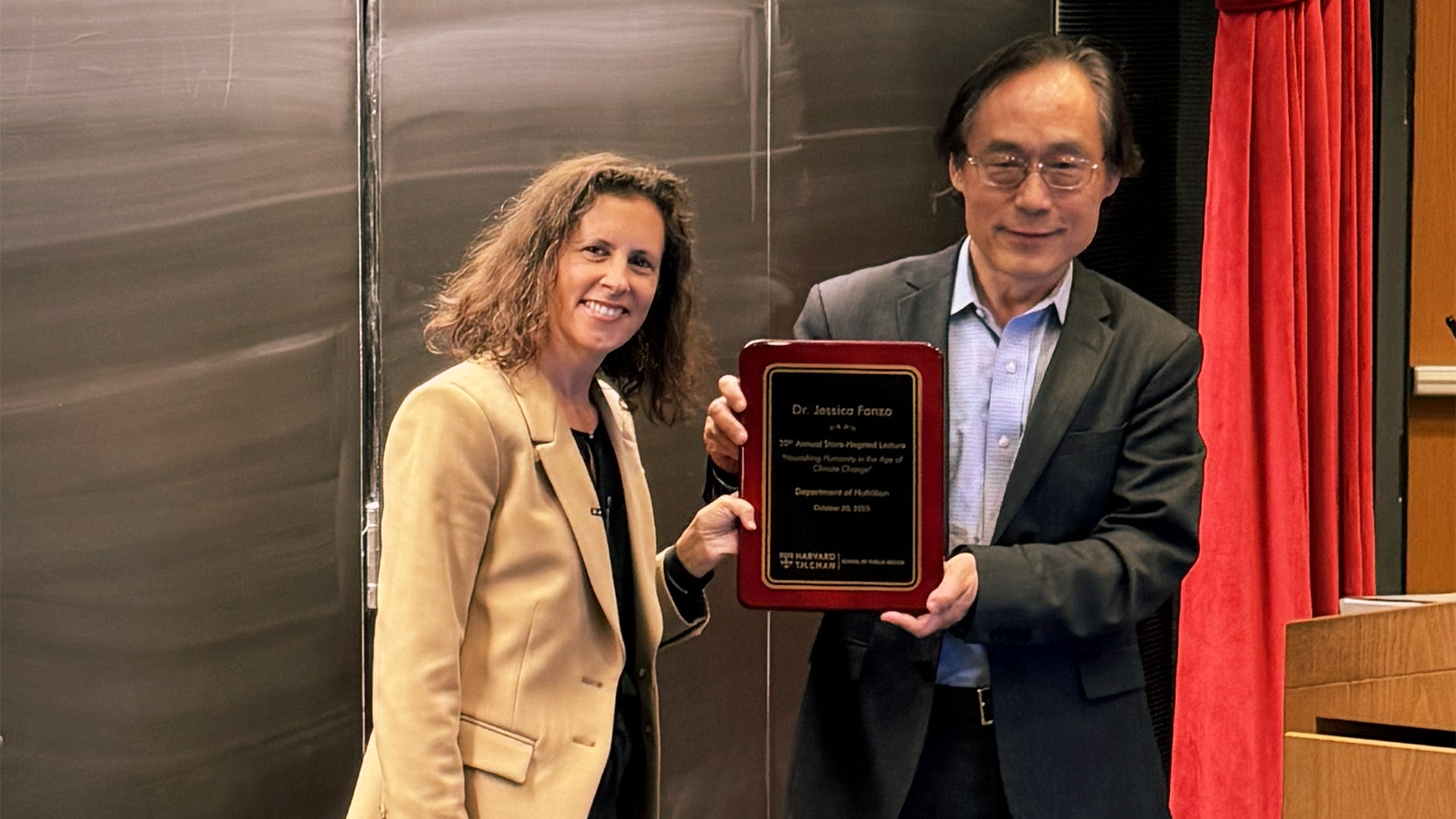

Fanzo, professor of climate and food and director of the Food for Humanity Initiative at Columbia University’s Climate School, delivered the 20th annual Stare-Hegsted Lecture on Oct. 20 in Kresge G2. Sponsored by the Department of Nutrition, the event honors department founders Fredrick Stare and D. Mark Hegsted.

She currently leads the Food Systems Dashboard and the Food Systems Countdown to 2030 Initiative, two collaborative efforts to monitor global food systems.

Fanzo noted that both undernutrition and overweight are significant problems around the world. For example, 733 million people go to bed hungry every night and 2.5 billion adults are overweight or obese. She said that making food systems more efficient and less wasteful can be a way to improve both climate and nutrition-related health outcomes.

Food systems have evolved since the 1960s, when the main concern in global food policy was addressing widespread famines, she said. Efforts have since shifted to not just alleviating hunger, but improving nutrition, and now, toward addressing human and planetary health—for example, as outlined in the EAT-Lancet report.

It can be difficult to keep food systems on the global policy agenda given political polarization and competing priorities, Fanzo said. She and her team are trying to do this by providing data that can be used to inform decision making. Their dashboards include country snapshots across a range of indicators in diets, nutrition, and health. A key part of this effort is to try to understand the impacts of climate on nutrition outcomes, she said.

“How does heat impact stunting and obesity? What about cold waves? What are the mechanisms for why with droughts you see more wasting?” she said. Much more research is needed on the impact of climate change, she said, and suggested that the students in the audience take on such questions.

Fanzo and her colleagues are also looking at crops that will do well in a changing climate, such as sorghum and some millet varieties, that are indigenous and culturally relevant in African countries and more nutritious than current staple crops such as maize. In addition, her team is developing actionable information for public health nutritionists such as early warning signs of a drought. Researchers need to better understand inequities around climate impact and ensure that information about how to address it reaches those who need it the most, she said.

Reflecting on the current challenges facing scientists, Fanzo told the students in the audience, “Keep doing what you’re doing. More than ever, science, data, and evidence is important and can chart a positive path. It can matter.”