Understanding Ovulation Disorders: Types, Causes, and New Research

The menstrual cycle is like an orchestra. Beautiful, right? Yes – under the right circumstances. Your hormones and organs prepare for months in advance to ensure they are in harmony, under careful direction from their conductor: your brain.

But when the soloist misses a cue, or equipment stops working? The entire performance can be thrown off. Sometimes, it picks back up and ends on a high note – other times, the lights go down and the curtains get drawn as the tech crew run around frantically backstage, trying to figure out what went wrong.

For people with ovulation disorders, it can be hard to know what even started the confusion. Sometimes, things recover, and the show goes on. Other times, it doesn’t. While many people think of ovulation as being the star of the show, think of it more like the applause; without the rest of the performance going well first, it doesn’t happen.

And that silence? It’s loud.

What are ovulation disorders?

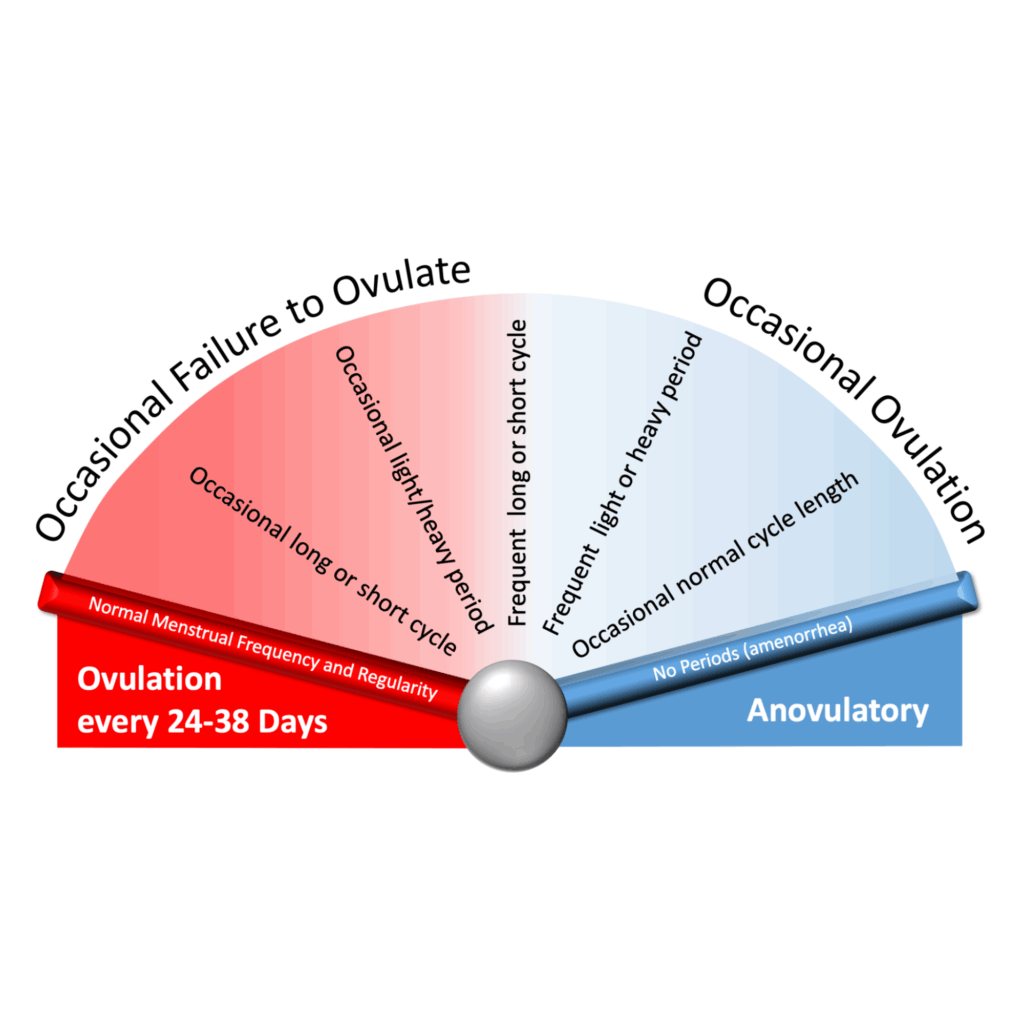

Ovulation disorders occur when the full ovulation process is disrupted, or it doesn’t happen regularly. They can affect whole body health, and they are a common cause of infertility.

Why do ovulation disorders matter?

Many people know that ovulation disorders can be linked with infertility, but what is important to remember is that they truly affect the health of the whole body. Irregular ovulation can affect bone, metabolic, and heart health over time1.

For example, last year, the Apple Women’s Health Study found that having persistently irregular menstrual cycles is linked with heightened risk for cardiometabolic conditions2. Authors Wang et al. highlighted that with how impactful ovulation disorders can be on health, we need to work towards earlier screening and intervention to prevent worse outcomes.

How are ovulation disorders diagnosed?

According to Dr. Shruthi Mahalingaiah, who is board certified in Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Endocrinology, the first step is that the patient comes into the doctor’s office or a medical clinic so that they can get the right tests. Their clinician (for example, their doctor) will perform a targeted physical examination. They will also ask the patient different questions to better understand the patient’s family and medical history, their health concerns, and their lifestyle overall. After this, there are blood tests (often called “lab work”). Depending on what the clinician finds, there may be additional tests, such as an ultrasound or biopsy.

The clinician evaluates all of the information from the exams, tests, and discussions with the patient to make any potential diagnosis before walking the patient through what they need to know. Learn more here3.

Causes that might surprise you

While ovulation disorders are often influenced by things like genetics, other factors like lifestyle, exercise/eating patterns and more can also disrupt the body’s ovulation process. For example, common but often underdiscussed influences can include:

- Psychological stress;

- Eating disorders;

- Low body weight;

- Excessive exercise;

- Or, a combination of these factors4.

Sometimes, the reasons are unknown. When this happens, doctors will call the cause “idiopathic.” That doesn’t mean nothing is wrong; it just means no one is sure why something is wrong yet.

Are there different types of ovulation disorders?

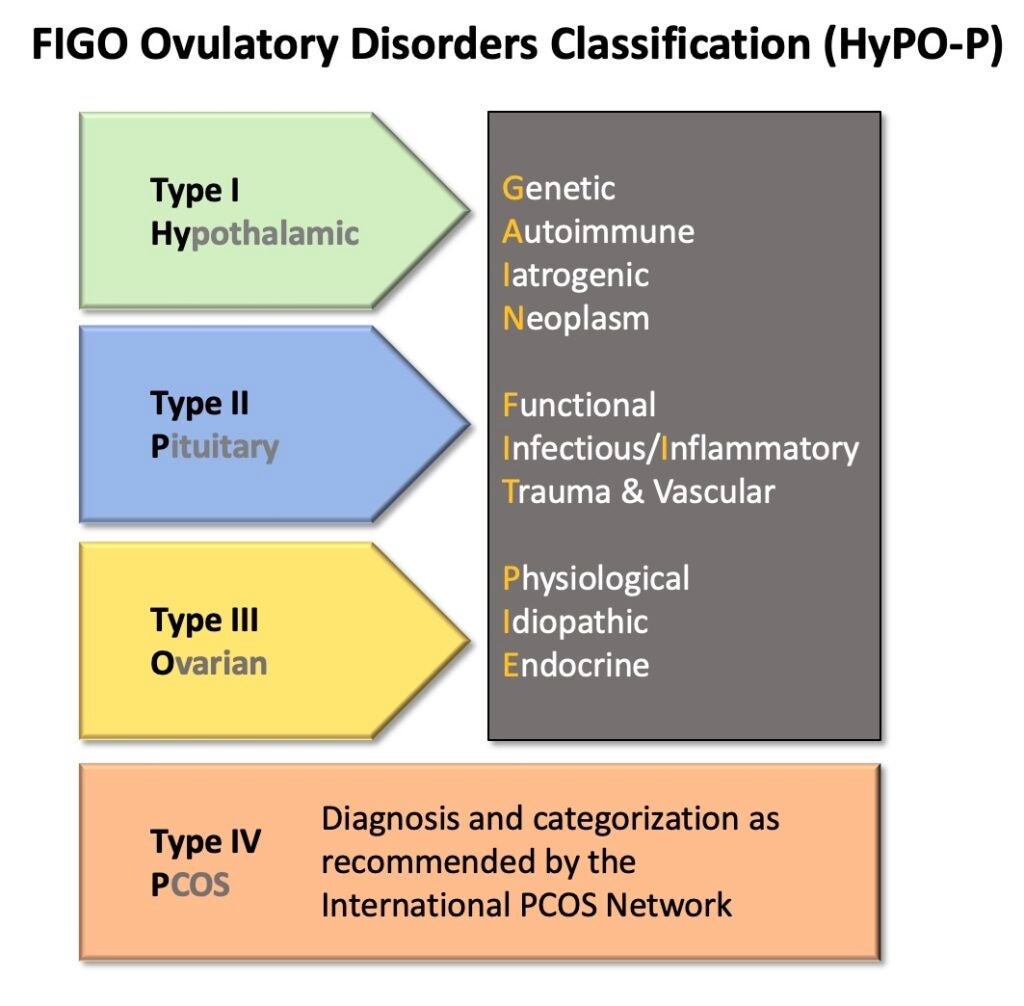

According to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), there are four main types of ovulation disorders5. They’re based on how and why ovulation is disrupted. This classification helps doctors understand exactly where along the ovulation process things aren’t working as they should. FIGO created the graphics below and a resource for patients to help explain the classification system here.

Let’s go through the four main types and their causes more in depth:

Type I: Hypothalamic

These disorders involve issues with the hypothalamus, which is a region of the brain that acts like a central command center for ovulation hormones.

Some common examples of patients with hypothalamic ovulation disorders can include, for example, people who stop ovulating due to significant psychological stress, or athletes that don’t fuel themselves with enough energy to recover from their training.

Causes According to FIGO (Explained Simply):

- Genetic (inherited or DNA-related factors)

- Autoimmune (when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues)

- Less commonly, iatrogenic (caused by medical treatment, like chemotherapy)

- Neoplasm (tumor-related)

Type II: Pituitary

These disorders involve issues with how the brain and ovaries talk to each other. Even though hormone levels are usually normal, ovulation still doesn’t happen.

When the brain is under perceived stress, for example, it can put reproduction processes on hold as it prepares to save energy for later or focus on survival6.

Causes According to FIGO (Explained Simply):

- Functional (problems with how an organ works)

- Infectious/inflammatory (infections or inflammation-related)

- Trauma and vascular (due to injury or problems with blood flow)

Type III: Ovarian

These disorders happen when there are issues with the ovaries themselves. It’s like they have Do Not Disturb turned on; no matter how many times the brain tries to call, the ovaries never “answer” to ovulate.

For example, this could happen when someone experiences early menopause, which is called “premature ovarian failure” or “primary ovarian insufficiency.”

The causes for early ovarian failure leading to irregular periods include genetic factors/familial predisposition, history of chemotherapy that is toxic to the ovaries and pelvic radiation, and rare forms of autoimmunity.

Causes According to FIGO (Explained Simply):

- Physiological (natural body processes, like puberty or menopause)

- Idiopathic (unknown)

- Endocrine (hormone-related)

Type IV: PCOS (Polycystic Ovary Syndrome)

Type IV is a distinct category just for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). PCOS is a complex disorder impacting the whole body. Symptoms can include irregular or absent ovulation and more. Despite its namesake, PCOS is actually not caused by a problem with the ovary or ovaries themselves; it’s more like a response to dysregulated hormonal signals and endocrine messaging miscommunication within the body. This can include, for example, between the brain and the ovaries.

Out of all four types of ovulation disorders, PCOS is the most common, but it’s still underdiagnosed7. It impacts about 6-12% of reproductive-age women in the United States7. PCOS has no single known cause. Instead, a combination of factors is believed to possibly contribute to its development8.

Recent research findings

At the Mahalingaiah Lab, our team is dedicated to finding new ways to support ovulation disorder patients, both through research and education. Many of our studies involve using the latest advancements in digital platforms and technology. Several recent publications address the impact of ovulation disorders in depth, finding that for example:

- Mothers who had higher levels of a certain ‘forever chemical’ (EtFOSAA) in their plasma were linked to a higher chance of their teenage daughters having PCOS9.

- People who have their first period earlier or take longer for their periods to become regular may have a higher risk of developing gestational diabetes during pregnancy later in life10.

- Among patients who came to a large healthcare facility for tests or symptoms like androgen blood tests, hirsutism, irregular periods, pelvic ultrasound, or PCOS evaluation, certain groups of people were more likely to have PCOS diagnoses missed. These groups included Black or African American patients, those using Medicaid or charity care, and people living in more socially vulnerable areas7.

Our work continues, too. Our scientists are investigating big questions about our health and how we can advance science for patient care.

Taking action and finding support

Ovulation disorders can be truly impactful on day-to-day life, and they aren’t in your head. Monitoring your menstrual cycle patterns can help provide valuable insight both to yourself and to your health care team. But it’s important to remember that while early diagnosis and support can improve both reproductive and whole-body health, it’s not always easy.

If you’re struggling with an ovulation disorder, you’re not alone. Your quality of life matters.

To learn more about current research studies working to advance outcomes for patients and recent findings, visit the Mahalingaiah Lab website.

References

1: Z. Wang, G. Asokan, J.-P. Onnela, D. D. Baird, A. M. Z. Jukic, A. J. Wilcox, C. L. Curry, T. Fischer-Colbrie, M. A. Williams, R. Hauser, B. A. Coull and S. Mahalingaiah, “Menarche and Time to Cycle Regularity Among Individuals Born Between 1950 and 2005 in the US,” JAMA Netw Open, vol. 7, no. 5, 2024.

2: Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, “Irregular periods linked with increased risk for cardiometabolic conditions,” 23 May 2024. [Online]. Available: https://hsph.harvard.edu/news/irregular-periods-linked-with-increased-risk-for-cardiometabolic-conditions/.

3: S. Mahalingaiah, “How I determine the causes of irregular periods,” 26 September 2018. [Online]. Available: https://helloclue.com/articles/cycle-a-z/how-i-determine-the-causes-of-irregular-periods.

4: A. E. Morrison, S. Fleming and M. J. Levy, “A review of the pathophysiology of functional hypothalamic amenorrhoea in women subject to psychological stress, disordered eating, excessive exercise or a combination of these factors,” Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), vol. 95, no. 2, pp. 229-238., 2021.

5: M. G. Munro, A. H. Balen, S. Cho, H. O. D. Critchley, I. Díaz, R. Ferriani, L. Henry, E. Mocanu and Z. M. v. d. Spuy, “The FIGO ovulatory disorders classification system,” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, vol. 159, no. 1, pp. 1-20, 19 August 2022.

6: A. Olsen and S. Mahalingaiah, “Dancing With the Endocrine System,” in Moving Between Worlds, Middletown, Wesleyan University Press, 2022, p. 17.

7: E. L. Silva, K. J. Lane, J. J. Cheng, Z. Popp, v. Loenen, B. D., Coull, B., J. E. Hart, T. James-Todd and S. Mahalingaiah, “Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Underdiagnosis Patterns by Individual-level and Spatial Social Vulnerability Measures,” J Clin Endocrinol Metab, vol. 110, no. 6, pp. 1657-1666, 2025.

8: E. Peebles and S. Mahalingaiah, “Environmental Exposures and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Review,” Semin Reprod Med, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 253-273, 2024.

9: Z. Wang, A. Fleisch, S. L. Rifas-Shiman, A. M. Calafat, T. James-Todd, B. A. Coull, J. E. Chavarro, M.-F. Hivert, R. C. Whooten, W. Perng, E. Oken and S. Mahalingaiah, “Associations of maternal per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance plasma concentrations during pregnancy with offspring polycystic ovary syndrome and related characteristics in project viva,” Environ Res, vol. 268, no. 120786, 2025.

10: Z. Wang, D. D. Baird, M. A. Williams, A. M. Z. Jukic, A. J. Wilcox, C. L. Curry, T. Fischer-Colbrie, J.-P. Onnela, R. Hauser, B. A. Coull and S. Mahalingaiah, “Early-life menstrual characteristics and gestational diabetes in a large US cohort,” Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, vol. 38, no. 8, pp. 654-665, 2024.