Apple Women’s Health Study

The Apple Women’s Health Study is the first long-term research study of this scale and scope that aims to advance the understanding of menstrual cycles and their relationship to various health conditions.

Pregnancy attempts during the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 impacted daily life and possibly the decision to attempt to get pregnant.

COVID-19 impacted daily life and possibly the decision to attempt to get pregnant. Initial data analysis shows a decrease in pregnancy attempts by almost 20% from May to October 2020.

SEPTEMBER 2021: Over the past decade, the U.S. has seen a steady decline in birth rates. Provisional data from the National Center for Health Statistics show that the U.S birth rate decreased by 4% from a total of 3,747,540 births in 2019 to 3,605,201 births in 2020.

COVID-19 has caused tremendous economic loss, unemployment, and uncertainty about the future. Historically, there have been fewer births during times of insecurity, for example over a century ago during the 1918 Spanish Flu and more recently, the 2008 Great Recession. Between 2008 and 2009, the birth rate dropped 2%.

People tend to make individual decisions that they perceive to be less risky during natural disasters, such as a global pandemic. For this reason, people might avoid or postpone pregnancy because of the potential, unknown changes in their lifestyle and financial situation.

It can be challenging to gather population level data on pregnancy attempts, which occurs approximately 10 months or more before birth. To fully understand gynecological and menstrual health, the Apple Women’s Health Study asks participants about attempts at pregnancy over time. Since this is a digital study, we were able to continue learning about pregnancy goals, uninterrupted, throughout the pandemic.

Data analysis to understand pregnancy attempts

Participants are asked about pregnancy planning through the Monthly Survey: Menstrual Update, which is sent to participants on the first Sunday of each month. Participants included in this study update analysis enrolled from November 14, 2019 (the start of the study) through March 31, 2021. To understand trends in pregnancy attempts during the COVID-19 pandemic, we analyzed responses to the below question, completed over time from February 2020 through May 2021.

Question: Did you actively try to get pregnant in the previous calendar month?

Participants that indicated “Yes” were included as actively trying to get pregnant. Participants that were already pregnant, lactating, in menopause, or had a hysterectomy were excluded from the analysis. This study update analysis compares the number of Monthly Survey: Menstrual Update respondents who reported attempting pregnancy to the number of respondents who were able to get pregnant.

Pregnancy attempts decreased from May to October 2020

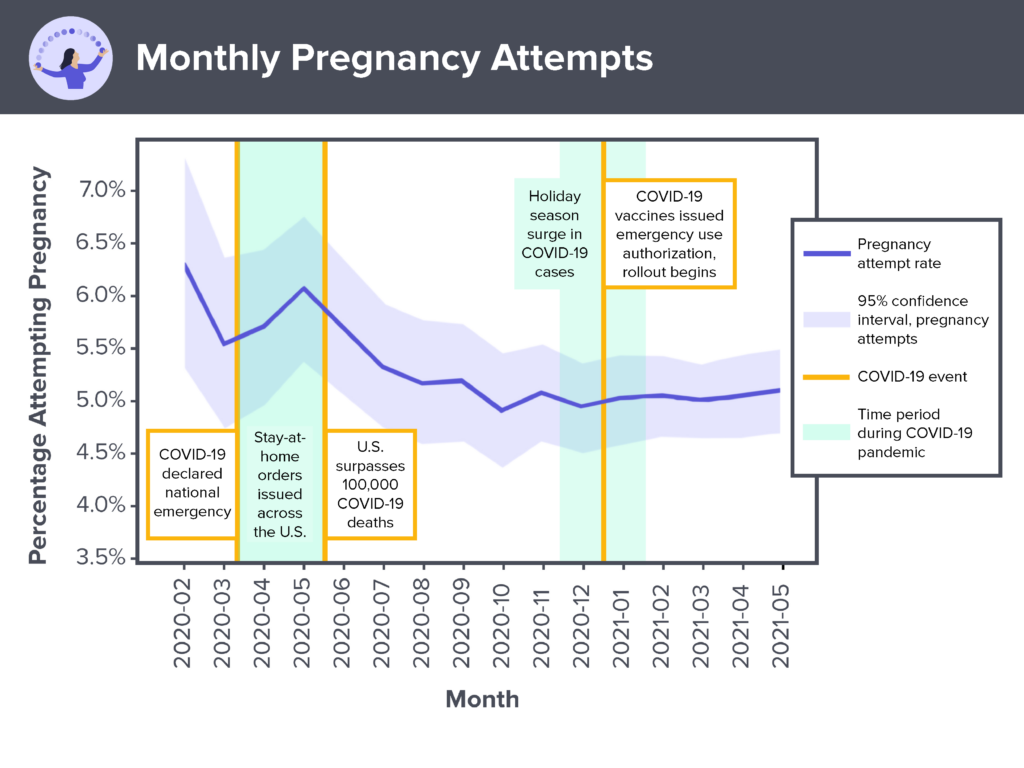

Overall, pregnancy attempts decreased from 6.1% in May 2020 to a low of 4.9% in October 2020. To investigate trends, we paired pregnancy attempt rates with key events and time periods during the pandemic. These include the COVID-19 national emergency declaration, stay-at-home orders, peaks in infection rates, and vaccine rollout.

Figure 1 below depicts the percentage of study participants attempting pregnancy over time.

The percentage of participants attempting pregnancy dropped from 6.3% in February 2020 to 5.5% in March 2020, which is when the COVID-19 pandemic was declared a national emergency by the U.S. government.

As stay-at-home orders were issued by states from March through May 2020, pregnancy attempts among respondents included in this analysis rose to 6.1% in May 2020. While multiple factors might be at play, one hypothesis is that people who were more hopeful that an end to the pandemic was near might have been more willing to try to get pregnant.

The U.S. surpassed 100,000 deaths from COVID-19 at the end of May 2020. A second wave of cases peaked at about 68,000 cases per day in mid-July, dipping down to about 35,000 cases per day in mid-September. Cases rose above 50,000 cases per day at the end of October 2020, the beginning of a third, large wave of cases. Between May and October 2020, the percentage of respondents who were attempting pregnancy dropped from 6.1% to 4.9%—a 20% decrease.

Pregnancy attempt rates stayed consistent around 5% for November 2020 through May 2021. Corresponding to this time window, cases rose to over 200,000 per day in mid-December 2020, and vaccine rollout began at the end of December 2020 after two COVID-19 vaccines, Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, were issued emergency use authorization by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Throughout January to May 2021, vaccines were administered to people across the country, and cases dropped to approximately 18,000 per day by the end of May.

More analysis is needed to understand the relationship between pregnancy attempts and key events and other factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disparities in the economic and health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic across demographics could have impacted pregnancy attempts. According to the Economic Policy Institute, 80% of jobs lost in 2020 were held by people in the bottom 25% of the income distribution. The leisure and hospitality sector lost the largest number of jobs, with Black and Hispanic women experiencing disproportionate losses.

In future analyses, our study team plans to investigate trends in pregnancy attempts by demographics to better understand disparities in the impact of COVID-19 on the decision to attempt pregnancy.

People who aren’t currently menstruating contribute important data

Understanding menstruation and the factors that could impact it, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, is important for scientific discovery. Menstrual health research can identify ways to treat gynecologic conditions and diseases in order to improve health and well-being of people who menstruate across the globe.

Although a large part of the Apple Women’s Health Study is centered around menstrual cycles, participants do not currently need to have a period to participate.

To understand the full picture of menstruation, we are collecting data from people across the lifespan and reproductive stages, including those who might not currently get a period. This includes people who are pregnant, are breastfeeding, on birth control, have certain gynecologic conditions that may stop menstruation, or have reached menopause.

The study team thanks participants, like you, for your continued participation. We encourage you to continue contributing data as you move through different life and reproductive stages.

The Apple Women’s Health Study is enrolling participants. If you would like to join, download the Research App.

- Adler, N., & Stewart, J. (2007). The MacArthur scale of subjective social status. San Francisco: MacArthur Research Network on SES & Health.

- Bloom-Feshbach, K., Simonsen, L., Viboud, C., Mølbak, K., Miller, M. A., Gottfredsson, M., & Andreasen, V. (2011). Natality decline and miscarriages associated with the 1918 influenza pandemic: the Scandinavian and United States experiences. The Journal of infectious diseases, 204(8), 1157–1164. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jir510

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021, May 28. [Media Statement]. United States Coronavirus (COVID-19) Death Toll Surpasses 100,000. Accessed online.

- Congressional Research Service. (2021, June 15). Unemployment Rates During the COVID-19 Pandemic. R46554.

- Decker, S., & Schmitz, H. (2016). Health shocks and risk aversion. Journal of health economics, 50, 156-170.

- FEMA. (2021, March 12). COVID-19 Disaster Declarations. Accessed online.

- Gould, E., and Jori, L. (February 2021). Wages Grew in 2020 Because the Bottom Fell Out of the Low-Wage Labor Market: The State of Working America 2020 Wages Report. Economic Policy Institute, February 2021. Accessed online.

- Gould, E., and Kassa, M. (May 2021). Low-wage, low-hours workers were hit hardest in the COVID-19 recession: The State of Working America 2020 Wages Report. Economic Policy Institute, May 2021. Accessed online.

- Hamilton, B.E., Martin, J.A., & Osterman, M.J.K. (May 2021). Births: Provisional Data for 2020. Vital Statistics Rapid Release Report No. 012. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed online.

- Livingston, G., & Cohn, D. (2010). US birth rate decline linked to recession. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved January, 19, 2012. Accessed online.

- Monte, L. (March 15, 2021). Historical Look at Unemployment, Sectors Shows Magnitude of COVID-19 Impact on Economy. Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division. United States Census Bureau. Accessed online.

- Moreland A, Herlihy C, Tynan MA, et al. Timing of State and Territorial COVID-19 Stay-at-Home Orders and Changes in Population Movement — United States, March 1-May 31, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1198–1203. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6935a2

- Usher, K., Durkin, J., & Bhullar, N. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health impacts. International journal of mental health nursing, 29(3), 315–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12726

- World Bank. (n.d.). Fertility rate, total (births per woman) – United States. Accessed online.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2021, June 6). Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine. Accessed online.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2021, April 4). Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine. Accessed online.