Apple Women’s Health Study

The Apple Women’s Health Study is the first long-term research study of this scale and scope that aims to advance the understanding of menstrual cycles and their relationship to various health conditions.

Menstrual cycles today: how menstrual cycles vary by age, weight, race, and ethnicity

The Apple Women’s Health Study explores how age, weight, race, and ethnicity affect menstrual cycles. Menstrual cycle data and responses to survey questions contributed by participants continue to help better understand menstrual health in modern living.

NOVEMBER 2022: A person’s menstrual cycle length and regularity are key indicators of their overall health1. Menstrual cycles that are unusually long (more than 40 days) or are irregular have been linked to infertility and cardiometabolic diseases such as coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes2–6. People with different racial and ethnic backgrounds – as well as those with different ages and weights – could have different patterns for cycle length and regularity. Understanding differences in menstrual patterns among groups may help patients and their clinicians personalize their healthcare.

The length of a cycle – defined as the number of days between periods, counting from the first day of one period to the day before the next period starts – is 28 days on average across the entire adult population7, but some variability is natural even in cycles that are considered regular.

Using cycle tracking and survey data from the Apple Women’s Health Study (AWHS), we explored and evaluated potential differences in menstrual cycle length and variability by age, weight, race, and ethnicity. We found that the length and regularity of menstrual cycles change over a person’s life. Menstrual cycles started out relatively long, around 30 days for younger people under 19 years old. They tended to shorten among people in older age groups, to an average of 28 days for those in their late 40s; but then became longer again after age 50. Similarly, menstrual cycles were less regular in the first few years after the first period and tended to become more regular among people in older age groups. However, after age 45, menstrual cycles started to become increasingly irregular with advancing age. People with higher body mass index (BMI) tended to have longer and more variable cycles.

Our main finding was compared to participants who were White; participants who were Asian and who were Hispanic had longer and more variable menstrual cycles. Black participants had similar menstrual cycle length and variability with those who were White.

Our findings also confirmed previous observations of how menstrual cycles change with age and body weight.

Evaluating menstrual cycle length and variability in AWHS

In this analysis, we included 165,668 menstrual cycles from November 2017 to December 2021 from 12,608 AWHS participants who did not report a history of polycystic ovary syndrome, uterine fibroids, hysterectomy, or current hormone use. The average age for those who were included was 33 years old. Over 70% of these participants were White, non-Hispanic, with smaller proportions of Black, Asian, Hispanic, and other race and ethnicity groups. Approximately 26% of participants had BMI between 25-30 kg/m2 (which is considered overweight by BMI criteria) and 35% of our participants had a BMI above 30 kg/m2 (which is considered obese by BMI criteria)8.

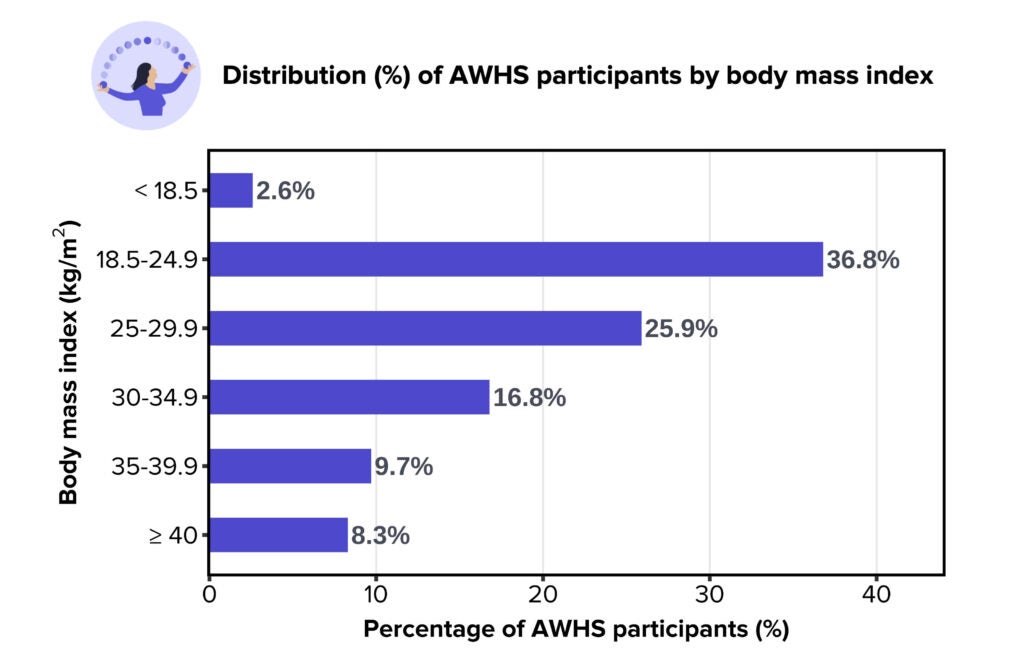

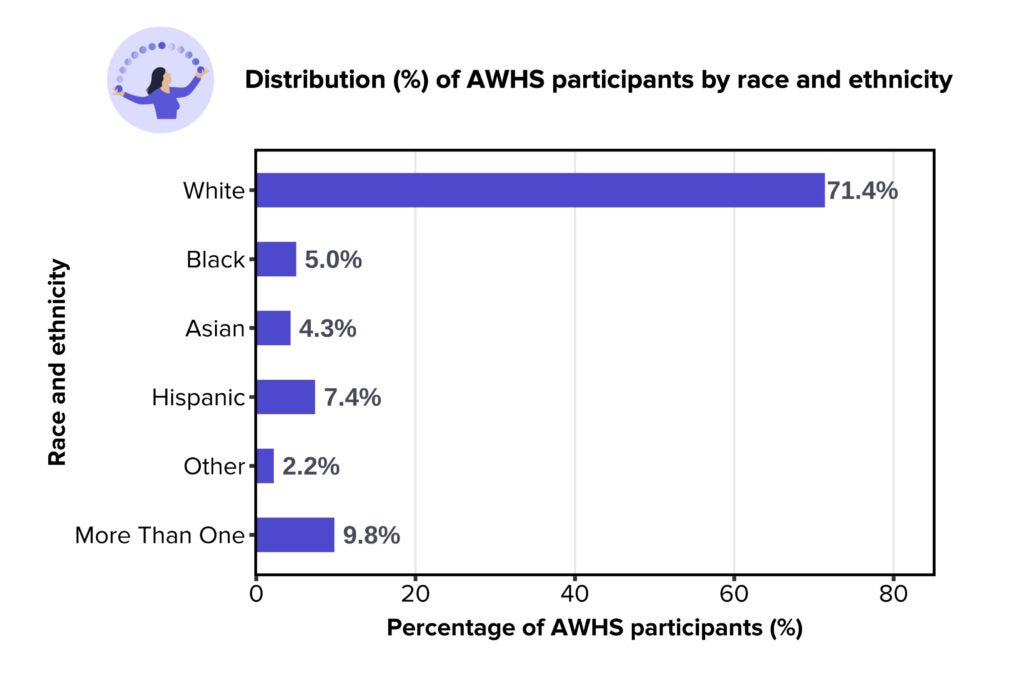

Here is the distribution of age, BMI, race, and ethnicity, among participants who contributed data to this study update:

Body mass index was calculated from the self-reported height and weight in the Common Demographics survey. These categories were defined based on the adult BMI classification from the Center of Disease Control and Prevention. Data presented in this chart is viewable in Table 1.

For race and ethnicity, the White group included participants who only selected ‘White, non-Hispanic’ in the Common Demographics survey; the Black group included participants who only selected ‘Black or African American or African’ in the survey; the Asian group included participants who only selected ‘Asian’; the Hispanic group included participants who only selected ‘Hispanic, Latino, Spanish and/or other Hispanic’; the Other group included participants who selected answers other than those mentioned previously (‘American Indian or Alaska Native,’ ‘Middle Eastern or North African’, ‘Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander,’ or ‘none of these categories can fully describe me’); the More Than One group included participants who selected more than one race and ethnicity options in the survey. Data presented in this chart is viewable in Table 1.

This analysis quantifies and compares menstrual cycle length, defined as the number of days from the first day of a period to the day before the next period starts, and the degree to which people’s cycle lengths varied, by age, race and ethnicity, and BMI. Days during the menstrual period were days a participant entered “having menstrual flow” in the Apple Health app. Age was calculated using the birth year reported by the participants and using the year of when a menstrual cycle occurs. BMI, race, and ethnicity were reported by participants through the Common Demographics survey in the Apple Research app.

Across the 165,668 cycles we analyzed, the average menstrual length was 28.7 days. This is consistent with previous observations on the typical menstrual cycle length in other populations 9–11.

Menstrual cycle length differs notably with age throughout the reproductive lifespan

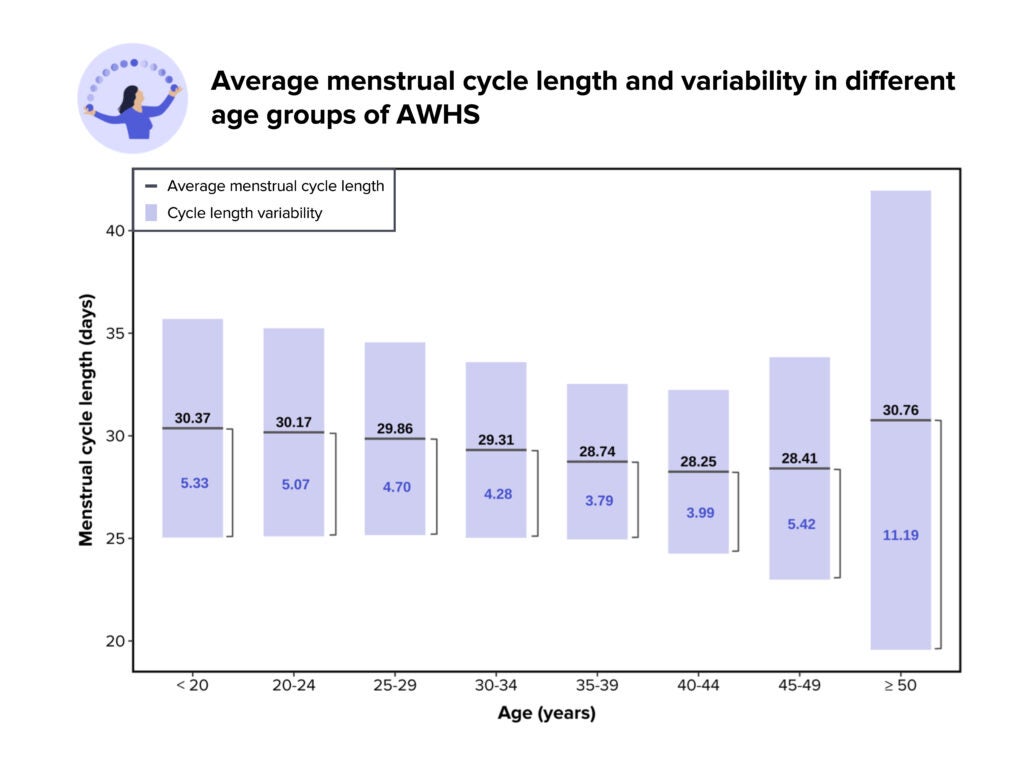

We found menstrual cycle length and variability differed considerably across the reproductive lifespan, from under 20 to above 50 years old. People under 20 years old had menstrual cycles 30.3 days long on average, 1.6 days longer than the 28.7-day average for those 35 to 39 years old. People 40 to 44 and 45 to 49 years old had shorter cycles, averaging 28.2 and 28.4 days, respectively. Those over 50 years old had longer cycles, averaging 30.8 days.

We found that people’s menstrual cycle lengths varied by on average 4 to 11 days depending on age. For instance, for people under 20 years old, menstrual cycle lengths varied by an average of 5.3 days. People ages 35 to 39 had the smallest variation, averaging 3.8 days. After age 40, cycles tended to vary more, ranging from 4-11 days on average. People who were above 50 years old had cycles that varied by an average of 11.2 days.

This graph presents the average menstrual cycle length and variability of AWHS participants in different age groups. Age was determined by the self-reported birth year and the year each cycle was tracked in the Health app. The variability was calculated as the average standard deviation of menstrual cycle length for an individual in that age group, meaning that 70% of the menstrual cycles of that individual are expected to vary within that range around the average. Data presented in this chart is viewable in Table 2.

These findings are similar to other research, including findings that menstrual cycles can be irregular for a few years after the first period (menarche), due to the immaturity of the reproductive system1. Our previous study update Periods, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and heart health suggested that menstrual cycles generally became regular within 4 years after menarche12. Menstrual cycles start to become less regular in a person’s early or mid-40s when ovarian function gradually declines. Eventually, menstruation stops permanently (menopause) after 1-3 years13 of long and highly irregular cycles, at around age 52, on average, for women in the US14.

Asian and Hispanic participants had longer menstrual cycles and higher variability

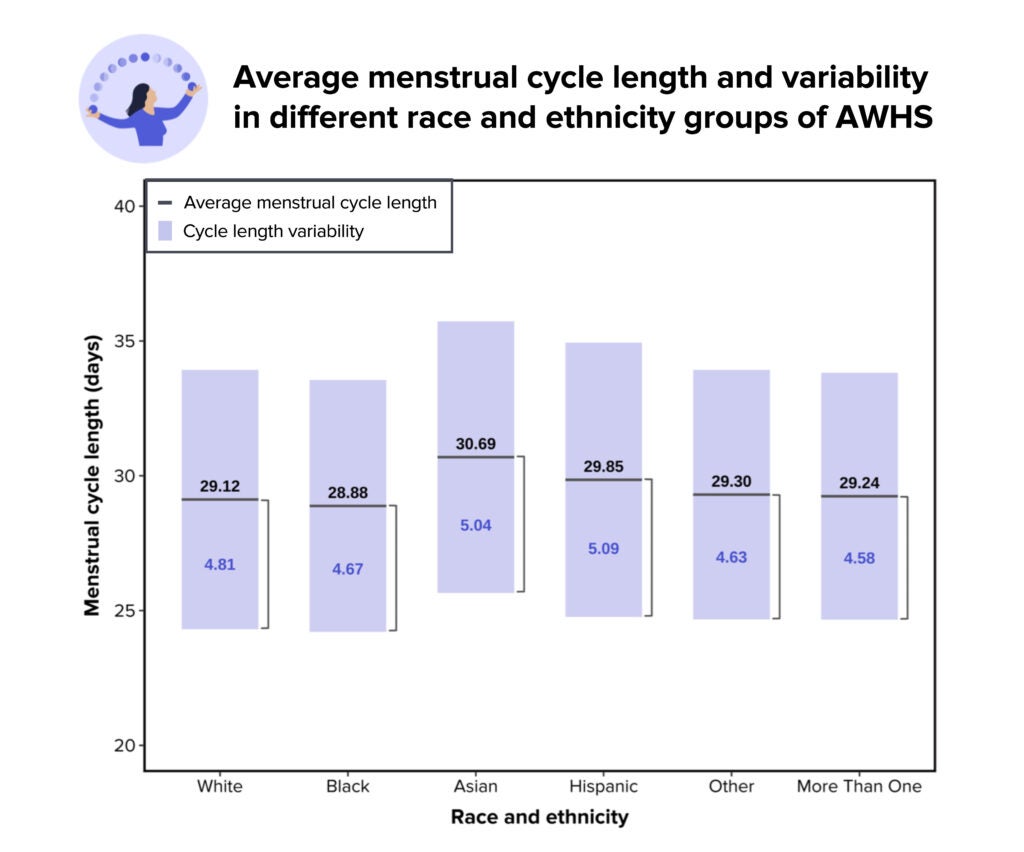

When we looked at menstrual cycle length by race and ethnicity groups, we found differences. On average, participants who identified as White had cycles lasting 29.1 days. Black participants had 28.9-day cycles, on average, 0.2 days shorter than those who were White. Participants who self-identified as Hispanic had cycles averaging 29.8 days, 0.7 days longer than White participants. Asian participants had even longer cycles, averaging 30.7 days, 1.6 days longer than White participants.

On average, White participants’ cycles varied around the average by 4.8 days, which lined up with Black participants’ cycle which varied around the average by 4.7 days. Asian and Hispanic participants’ cycles varied a bit more, by 5.04 and 5.09 days around the average cycle length, respectively.

This graph presents the average menstrual cycle length and variability of AWHS participants in different race and ethnicity groups. The White group included participants who only selected ‘White, non-Hispanic’ in the Common Demographics survey; the Black group included participants who only selected ‘Black or African American or African’ in the survey; the Asian group included participants who only selected ‘Asian’; the Hispanic group included participants who only selected ‘Hispanic, Latino, Spanish and/or other Hispanic’; the Other group included participants who selected answers other than those mentioned previously (‘American Indian or Alaska Native,’ ‘Middle Eastern or North African’, ‘Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander,’ or ‘none of these categories can fully describe me’); the More Than One group included participants who selected more than one race and ethnicity options in the survey. The variability was calculated as the average standard deviation of menstrual cycle length for an individual in that age group, meaning that 70% of the menstrual cycles of that individual are expected to vary within that range around the average. Data presented in this chart is viewable in Table 3.

Until now, there are still unanswered questions about whether there are racial or ethnic differences in menstrual cycle characteristics. Our study has identified that there are differences but has not investigated their causes. People in different race and ethnicity groups can have differential exposures to social, cultural, and environmental stressors, which can eventually affect their menstrual health. More studies are needed to explore the underlying mechanisms and factors.

Higher BMI was linked with longer cycle length and higher cycle variability

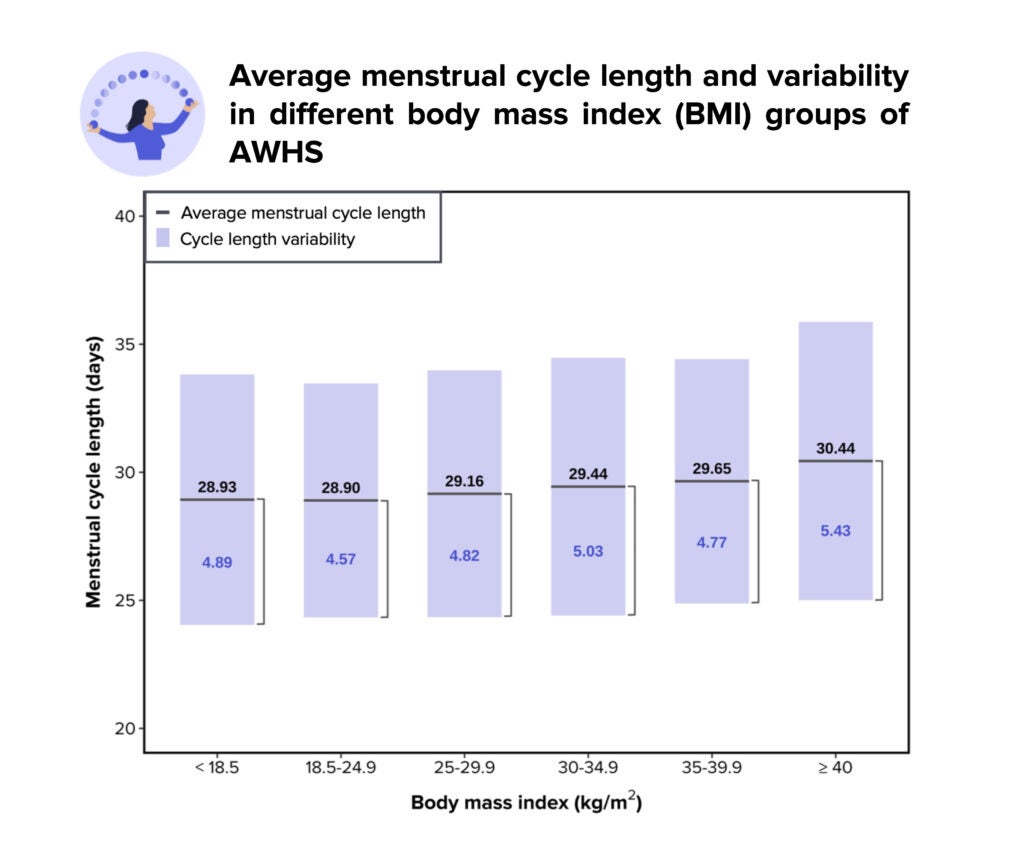

Compared to participants with BMI between 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 (healthy BMI range), those whose BMI was between 25-29.9 kg/m2 or above 30 kg/m2 had longer menstrual cycles and higher variability around the average menstrual cycle length. Participants in the healthy BMI range had cycles averaging 28.9 days, with variation of 4.6 days around the average cycle length. Those with a BMI between 30-34.9 kg/m2 had average cycles of 29.4 days, with 5.1 days of variation. Those with a BMI between 35-39.9 kg/m2 had average cycles of 29.6 days, with 4.8 days of variation and those with a BMI above 40 kg/m2 had average cycles of 30.4 days, with 5.4 days of variation.

This graph presents the average menstrual cycle length and variability of AWHS participants in different BMI groups. BMI was calculated using the self-reported height and weight in the Common Demographics survey. The variability was calculated as the average standard deviation of menstrual cycle length for an individual in that age group, meaning that 70% of the menstrual cycles of that individual are expected to vary within that range around the average. Data presented in this chart is viewable in Table 4.

Obesity, defined as a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, can affect menstruation in multiple ways. Individuals with obesity may experience hormonal disruption15. Estrogen is an important ovarian sex hormone regulating menstrual function. Fat tissue can produce a small amount of estrogen, in addition to normal estrogen production in the ovaries. People with excess fat tissue may be more likely to have estrogen excess, which may in turn suppress the ovarian function and interrupt the normal menstrual rhythm. Although this analysis did not include women with a known diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome, women with this condition are also more likely to have a higher BMI and experience menstrual irregularity12,16. See Study Update: Periods, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and heart health for reference. Obesity is a separate indicator of health risks, including menstrual health.

Importance of studying menstrual cycle differences

Menstrual cycle length and variability are important indicators of overall health. In addition to confirming previous observations of differences in menstrual patterns with age and body weight, our analysis demonstrates racial and ethnic differences of menstrual characteristics, which provide valuable background information on the possible social, cultural, and environmental factors of menstrual cycles for future research. So far the clinical guideline on menstrual cycle length is mostly based on evidence from the White population. Knowing how menstrual cycles differ among other groups can better help refining what should be considered normal for individuals with different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Our team looks forward to working with study participants to better understand the relationship between demographic and lifestyle factors and menstrual health, and the implication of menstruation on various health outcomes. Thank you to the participants for contributing important information to the Apple Women’s Health Study.

More information on Apple Research App & Privacy

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care, Diaz A, Laufer MR, Breech LL. Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):2245-2250. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2481

- Small CM, Manatunga AK, Klein M, et al. Menstrual Cycle Characteristics: Associations With Fertility and Spontaneous Abortion. Epidemiology. 2006;17(1):52-60. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000190540.95748.e6

- Wang YX, Arvizu M, Rich-Edwards JW, et al. Menstrual cycle regularity and length across the reproductive lifespan and risk of premature mortality: prospective cohort study. BMJ. Published online September 30, 2020:m3464. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3464

- Solomon CG, Hu FB, Dunaif A, et al. Menstrual cycle irregularity and risk for future cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(5):2013-2017. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.5.8471

- Small CM, Manatunga AK, Klein M, et al. Menstrual cycle variability and the likelihood of achieving pregnancy. Rev Environ Health. 2010;25(4):369-378. doi:10.1515/reveh.2010.25.4.369

- Wang ET, Cirillo PM, Vittinghoff E, Bibbins-Domingo K, Cohn BA, Cedars MI. Menstrual irregularity and cardiovascular mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):E114-118. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-1709

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists. The Menstrual Cycle: Menstruation, Ovulation, and How Pregnancy Occurs. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/infographics/the-menstrual-cycle

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Defining Adult Overweight & Obesity. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/adult-defining.html

- Harlow SD, Lin X, Ho MJ. Analysis of menstrual diary data across the reproductive life span Applicability of the bipartite model approach and the importance of within-woman variance. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2000;53(7):722-733. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00202-4

- Treloar AE, Boynton RE, Behn BG, Brown BW. Variation of the human menstrual cycle through reproductive life. Int J Fertil. 1967;12(1 Pt 2):77-126.

- Bull JR, Rowland SP, Scherwitzl EB, Scherwitzl R, Danielsson KG, Harper J. Real-world menstrual cycle characteristics of more than 600,000 menstrual cycles. npj Digit Med. 2019;2(1):83. doi:10.1038/s41746-019-0152-7

- Apple Women’s Health Study. Periods, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and heart health. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/applewomenshealthstudy/updates/periods-polycystic-ovarian-syndrome-and-heart-health/

- Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, et al. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Menopause. 2012;19(4).

- Office on Women’s Health. Menopause basics. https://www.womenshealth.gov/menopause/menopause-basics

- Silvestris E, de Pergola G, Rosania R, Loverro G. Obesity as disruptor of the female fertility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12958-018-0336-z

- Office on Women’s Health. Polycystic ovary syndrome. https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/polycystic-ovary-syndrome