Apple Women’s Health Study

The Apple Women’s Health Study is the first long-term research study of this scale and scope that aims to advance the understanding of menstrual cycles and their relationship to various health conditions.

Exploring Exercise Habits by Menstrual Cycle Phase

Researchers are studying patterns of exercise minutes and step count on bleeding vs. non-bleeding days for participants in the Apple Women’s Health Study.

MAY 2025: It’s no secret that exercise promotes good health1. Besides being fun and helping you feel great, exercising is associated with benefits for both body and mind. Some benefits include stronger bones and muscles, less risk of heart disease or stroke, and even better mood 2. Researchers also discovered that females who exercise regularly seem to have lower risks of deaths from any cause compared to males who also exercise regularly3.

Many factors influence someone’s interest and ability to exercise. For some, they may think about where they are in their menstrual cycle when deciding to exercise.

In this analysis, we look at what types of exercise participants are doing, and if the amount of exercise is different depending on where they are in their menstrual cycle.

Why is exercise so important? What does it have to do with my cycle?

Moving your body through exercise is one of the most important ways you can better your overall health both immediately and long term.

Short Term Benefits

- Better sleep4

- Less symptoms of depression and anxiety4

- Lower blood pressure4

Long Term Benefits

- Lower risk of falls and osteoporosis4

- Less joint pain and associated disability4

- Less risk of several types of cancer5

Many enjoyable physical activities count as exercise. Activities like walking, yoga, and dancing can be accessible, fun, and result in major payoffs. For good health, there are two types of exercise you should do regularly – provided that it is tolerated and safe for you and your specific medical considerations. These two types are: 1) aerobic (“cardio”) exercise and 2) muscle-strengthening exercise6. When in doubt, talking with your healthcare provider is a great start to identify good exercise habits. They can help you figure out what is right for your body.

What is cycle syncing?

Recently, many people have tried planning their exercise around different phases of their menstrual cycle – a trend called “cycle syncing.” Supporters of cycle syncing use this practice as a way to feel better and get more out of an exercise routine7. But, why?

The menstrual cycle has different phases, and during each one, your body produces different hormones (chemicals that carry messages throughout your body). Hormones control many important functions, such as reproduction and metabolism.

Each menstrual cycle has two main phases, which are divided by ovulation (when your ovary releases an egg):

- The first phase, from the first day of the period start to ovulation, is called the follicular phase. Estrogen and a hormone known as FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone) start to increase during this phase. The entire body is responsive to estrogen.

- The second phase, after ovulation until the start of the next period, is called the luteal phase. During this phase, a hormone called progesterone increases. Progesterone can promote smooth muscle relaxation8. Estrogen also fluctuates during the luteal phase.

While the idea of cycle syncing is popular, it’s important to know that scientists are still looking into it. Right now, there isn’t enough evidence to say that your hormone levels should change your exercise plans. Each person’s body is unique, and what works for one person might not work for another. Also, people with irregular cycles may not have the same hormone patterns to count on. Learning more about your menstrual cycle and how you as an individual can get the most out of exercise still has a lot of benefits9.

Who were the study participants included in this analysis?

To examine trends in exercise and step count across the menstrual cycle, we included the data of 110,740 participants ages 18-50 who had enrolled in the AWHS and consented to sharing their data. A total of 22.85 million workouts were logged across 461,163 collective cycle days (the total collective length of the data collection period for participants). Logs analyzed were collected from 11/16/2017 to 2/5/2025. Participants that logged less than 16 hours of watch wear time were excluded from data analysis.

Multiple data sources were used to analyze exercise and the menstrual cycle. Data sources included the demographics survey, the medical history survey, the reproductive history survey, Apple Watch Activity rings summary data, Apple Watch stand hours data, cycles data, and menstrual surveys.

Do participants exercise different amounts during the different cycle phases?

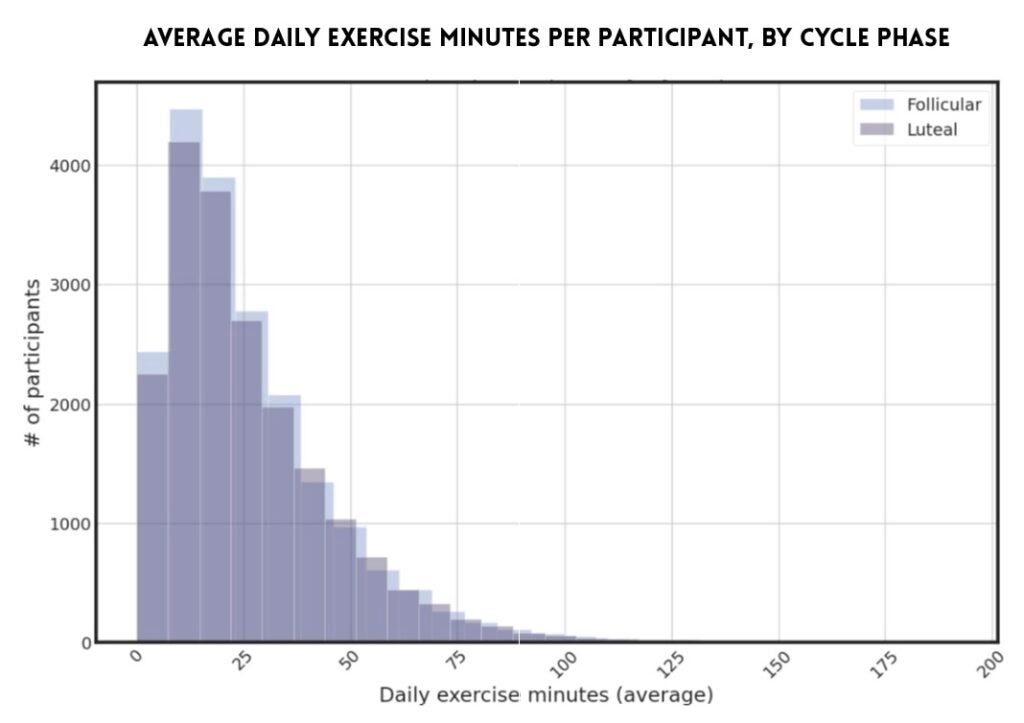

Cycle phases were labeled using the calendar method. The luteal phase included the last 14 days of a completed menstrual cycle. The amount of exercise was basically the same. During the follicular phase participants typically exercised 21 minutes a day, compared to 20.9 minutes during the luteal phase (Figure 1).

This makes sense, since it is safe to exercise while on your period10. Many types of exercise have even been linked with successfully reducing menstrual pain11.

Factors that can influence a person’s ability or interest in exercising are highly individual and wide ranging. If you are experiencing menstrual symptoms (such as painful cramps or tiredness) that limit your ability to get moving, even if only during different parts of your cycle, it is important to consult your medical care provider.

The average amount of daily exercise minutes per participant by cycle phase (follicular vs luteal) that we found is shown below. Daily exercise minutes were very similar, with participants exercising only slightly more overall during the follicular phase.

How did participants self-categorize their physical activity?

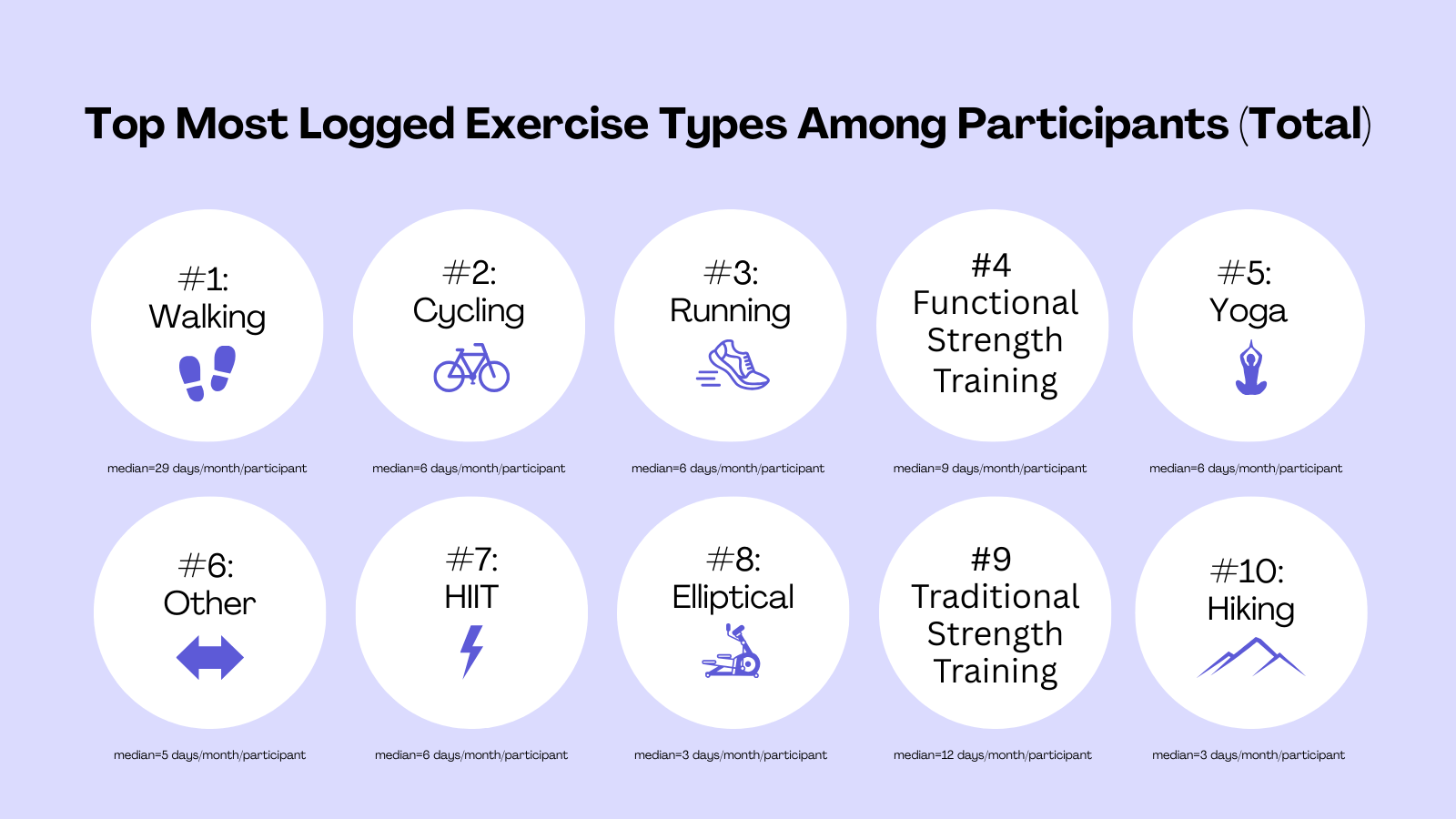

AWHS researchers show that walking, cycling, and running are the top three most logged exercise types among AWHS participants.

The image below (Figure 2) shows the top most logged exercise types (in order) among participants overall. The top three exercises were walking, cycling, and running.

Walking is particularly popular – among participants who have logged this activity type, they have been walking for a median of 29 days per month.

What differences can be found in exercise trends for participants with regular vs irregular cycles?

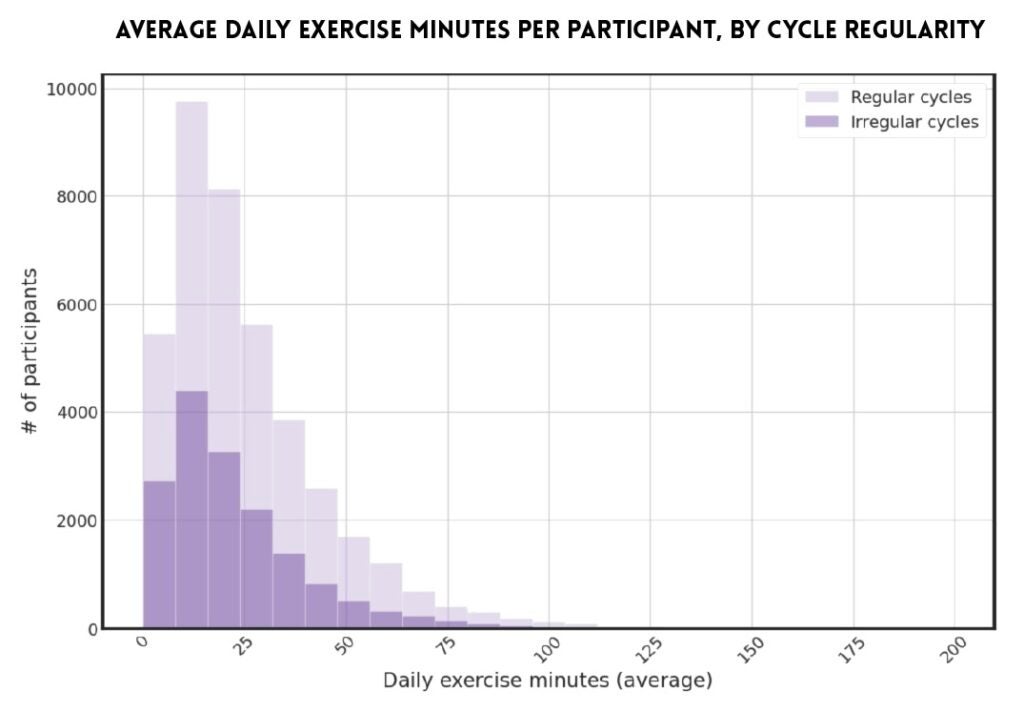

Participants who reported regular cycles reported exercising more minutes overall, compared to participants with irregular cycles (Figure 3). We defined regular and irregular cycles based on their survey responses. Participants with regular cycles typically had 20.6 minutes of exercise per day. Participants with irregular cycles typically had 18.6 minutes per day. Irregular cycles can be caused by many factors, some of which may make it hard to exercise.

The graph below shows the average number of exercise minutes per participant by cycle regularity (regular vs irregular cycles).

Conclusions

Exercise is important and can be beneficial during all stages of the menstrual cycle. Many people are staying active and reaping the benefits, like feeling happier, getting stronger, and reducing health risks.

Making aerobic and strength-training exercise a regular part of your life doesn’t have to be hard – it can be helpful to just find what you enjoy, and to stick with it. Among study participants, many are enjoying walking, cycling, and running. Remember, every step counts. Whether it’s a short walk or a jog, staying active is a great way to boost your health and feel great.

Here we describe how participants are choosing to exercise the same amounts during both phases of their menstrual cycle. This analysis is not the same as medical advice; it is important that anyone who is choosing to get exercise talks with their care provider about how to safely get the benefits of it. In the end, it’s important for each of us to listen to our own bodies and find what feels best. If a certain type of exercise makes you feel good at a certain time, that’s great! Keep doing what works for you. Remember, the goal is to stay active and healthy in a way that suits you and your specific needs.

The Apple Women’s Health Study team is grateful to its participants for their continued contributions to public health research.

More information on the Apple Research app & Privacy

- Office on Women’s Health, “Getting Active,” 4 February 2021. [Online]. https://womenshealth.gov/getting-active.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “10 Reasons to Get Moving Today!,” 6 February 2024. [Online]. https://www.cdc.gov/physical-activity/features/10-reasons-to-get-moving.html.

- H. Ji, M. Gulati, T. Y. Huang, A. C. Kwan, D. Ouyang, J. E. Ebinger, K. Casaletto, K. L. Moreau, H. Skali and S. Cheng, “Sex Differences in Association of Physical Activity With All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 83, no. 8, p. 783–793, February 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.12.019

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Physical Activity and Your Weight and Health,” 27 December 2023. [Online]. https://www.cdc.gov/healthy-weight-growth/physical-activity/index.html. [Accessed 19 February 2025].

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Physical Activity and Cancer,” 20 March 2024. [Online]. https://www.cdc.gov/physical-activity-basics/health-benefits/lowers-risk-of-cancer.html. [Accessed 19 February 2025].

- Office on Women’s Health, “How to be active for health,” 16 February 2021. [Online]. https://womenshealth.gov/getting-active/how-be-active-health. [Accessed 19 February 2025].

- A. Haridasani Gupta, “Cycle Syncing Is Trendy. Does It Work?,” The New York Times, 1 June 2023. [Online]. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/01/well/move/menstrual-cycle-syncing-exercise.html.

- O. A. Al-Shboul, A. G. Mustafa, A. A. Omar, A. N. Al-Dwairi, M. A. Alqudah, M. S. Nazzal, M. A. Alfaqih and R. A. Al-Hader, “Effect of progesterone on nitric oxide/cyclic guanosine monophosphate signaling and contraction in gastric smooth muscle cells,” Biomedical Reports, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 511-516, 2018. DOI: 10.3892/br.2018.1161

- K. L. McNulty, J. E.-S. Kirsty, E. Dolan, P. A. Swinton, P. Ansdell, S. Goodall, K. Thomas and K. M. Hicks, “The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Sports Med, vol. 50, no. 10, p. 1813–1827, 2020. DOI: 10.1007/s40279-020-01319-3

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Physical activity and your menstrual cycle,” 16 February 2021. [Online]. https://womenshealth.gov/getting-active/physical-activity-menstrual-cycle. [Accessed 19 February 2025].

- I.-C. Tsai, C.-W. Hsu, C.-H. Chang, W.-T. Lei, P.-T. Tseng and K.-V. Chang, “Comparative Effectiveness of Different Exercises for Reducing Pain Intensity in Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Sports Medicine – Open, no. 63, 2024. DOI: 10.1186/s40798-024-00718-4

- Office on Women’s Health, “Menstrual Cycle,” 22 February 2021. [Online]. https://womenshealth.gov/menstrual-cycle.

- Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, “Menstrual Cycles as a Fifth Vital Sign,” 13 September 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/org/od/directors_corner/prev_updates/menstrual-cycles. [Accessed 19 February 2025].

- L. R. Campbell, A. L. Scalise, B. T. DiBenedictis and S. Mahalingaiah, “Menstrual cycle length and modern living: a review,” Current Opinion in Endocrinology & Diabetes and Obesity, vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 566-573, 2021. DOI: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000681

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Adult Activity: An Overview,” 20 December 2023. [Online]. https://www.cdc.gov/physical-activity-basics/guidelines/adults.html. [Accessed 19 February 2025].

- P. F. Saint-Maurice, R. P. Troiano, D. R. Bassett Jr., B. I. Graubard, S. A. Carlson, E. J. Shiroma, J. E. Fulton and C. E. Matthews, “Association of Daily Step Count and Step Intensity With Mortality Among US Adults,” JAMA, vol. 323, no. 12, pp. 1151-1160, 2020. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2020.1382

- I.-M. Lee, E. J. Shiroma and M. Kamada, “Association of Step Volume and Intensity With All-Cause Mortality in Older Women,” JAMA Internal Medicine, vol. 179, no. 8, pp. 1105-1112, 2019. DOI: DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0899

- A. K. Rosen Vollmar, S. Mahalingaiah and A. M. Jukic, “The menstrual cycle as a vital sign: a comprehensive review,” F&S reviews, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 100081, 2025. DOI: DOI: 10.1016/j.xfnr.2024.100081