Apple Women’s Health Study

The Apple Women’s Health Study is the first long-term research study of this scale and scope that aims to advance the understanding of menstrual cycles and their relationship to various health conditions.

Understanding exercise patterns and heart rate throughout pregnancy

Researchers are studying the exercise and activity of pregnant participants during and after pregnancy.

JUNE 2024: Pregnancy is a time of change. For those who have experienced pregnancy and for those who have supported another person during pregnancy, the changes experienced or observed may include shifts in food preferences, digestion, exercise capacity, and physical changes to support pregnancy and the postpartum period. Other changes include mood shifts and sleep changes. Pregnancy has also been considered as a cardiac stress test on a pregnant person’s cardiovascular system. During pregnancy, it can be difficult for a person to know if the experienced changes are typical or not. There is very little information regarding exercise and trends across pregnancy. In this Study Update, the Apple Women’s Health Study (AWHS) is taking a deeper dive into what changes occur in exercise habits and heart rate during and after pregnancy.

Why is exercise important during pregnancy and postpartum?

Physical activity and exercise, as is safe and tolerated, have been shown to benefit most people who are pregnant. Some of the benefits are about easing symptoms commonly associated with pregnancy. Regular exercise including walking and swimming may help to reduce back pain, ease constipation, and support mood1. People who exercise routinely during pregnancy are more likely to have a vaginal birth rather than a cesarean delivery and have a lower chance of gaining excessive weight during pregnancy and developing gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.2 There is also the potential for exercise, as simple as walking, during pregnancy to improve birth outcomes, with some studies showing a decrease in premature birth and low birth weight3,4. After delivery and once cleared by a healthcare provider, exercise also helps to prevent complications, like deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or blood clots in the legs, can help improve mood, and can support a healthy weight after delivery1.

What are the recommendations around exercise in pregnancy and postpartum?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend at least 150 minutes of exercise per week during pregnancy and after delivery, once you have been cleared by a healthcare provider5,6. This amount of exercise can be broken into shorter workouts and spread across the week.

There are several types of exercises that experts agree are considered safest in pregnancy and postpartum. These include brisk walking, swimming, and water workouts, using a stationary bike, modified yoga, and modified Pilates. Pregnant individuals who are already in the habit of running, jogging, or playing some sports may be able to safely continue these activities in discussion with their care providers.

For all pregnant people, there are some warning signs to look out for when exercising, such as bleeding from the vagina, feeling dizzy or faint, regular and painful uterine contractions, or chest pain. Experiencing these can be a sign of a pregnancy complication and experts recommend stopping exercise and contacting a care provider right away5.

What are changes to the heart rate during pregnancy?

Early in pregnancy, the heart rate typically begins to increase and tends to keep increasing throughout the pregnancy, with a peak in the third trimester7,8. The amount of increase differs from person to person but has been shown to go up by 10 or 20 beats per minute by the end of pregnancy, which is often a 20% to 25% increase in resting heart rate9,10.

Some people may use their heart rate to guide their exercise when they are not pregnant. However, because of the expected changes to heart rate during pregnancy, heart rate may not be the ideal way to gauge exercise intensity. A better option to gauge exercise intensity during pregnancy is to use their own ratings of perceived exertion, aiming for exertion that feels somewhat hard5,11. Another way to determine if the amount of exercise is a reasonable intensity is the ‘talk test’. As long as the pregnant person who is exercising can carry on a conversation, or speak comfortably while exercising, they are likely not overexerting themselves5.

Who were the study participants included in this analysis?

To examine changes in exercise and heart rate during and after pregnancy, we included the data of 733 participants who had enrolled in AWHS from November 2019 through November 2023 and reported any pregnancy that lasted at least 24 weeks and less than 42 weeks and 6 days. Additionally, the participants had to have Apple Watch data in the weeks leading up to pregnancy (12 weeks), throughout the pregnancy, and after pregnancy (12 weeks).

This population (Table 1) had a median age of 32 years (range 20-45 years). 80.2% of the participants were White, non-Hispanic, while others were Black (2.5%), Asian (2.5%), Hispanic (5.2%), and other race and ethnicity groups (8.6%). For 34% of participants, this was their first pregnancy.

How did participants self-categorize their physical activity?

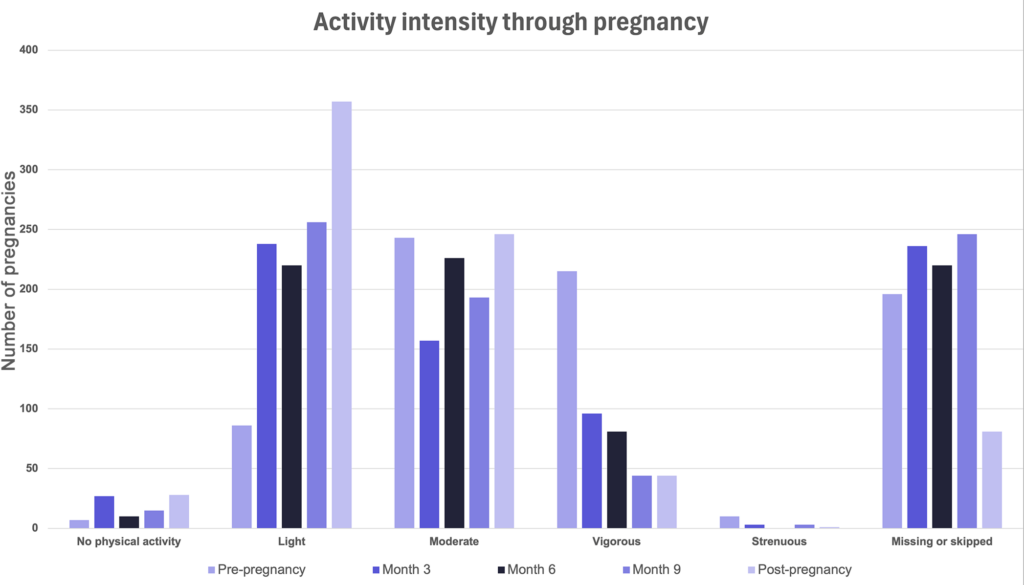

In a monthly survey, participants were asked the following question: During the past calendar month, how would you describe your overall physical activity level? Prior to pregnancy, 11% of participants described their activity as ‘light’, while 32% described it as moderate, 28% as vigorous, and 1% as strenuous, while 0.9% stated that they didn’t do any physical activity (Image 1).

As pregnancy progressed, an increasing number of participants reported doing light exercise (34% by the 9th month) and this was the most common reported intensity postpartum (47%).

Figure #1. Activity intensity through pregnancy. Distribution of survey responses, before pregnancy and during pregnancy, to the following question: During the past calendar month, how would you describe your overall physical activity level? Response options were the following: I didn’t do any physical activity; I participated in light activities, such as walking or light housework; I participated in moderate activities, such as brisk walking or yard work; I participated in vigorous activities, such as running or carrying heavy loads; I participated in strenuous activities, such as competitive sports or endurance events like marathons; I prefer not to answer.

What were the changes in total exercise minutes during and after pregnancy?

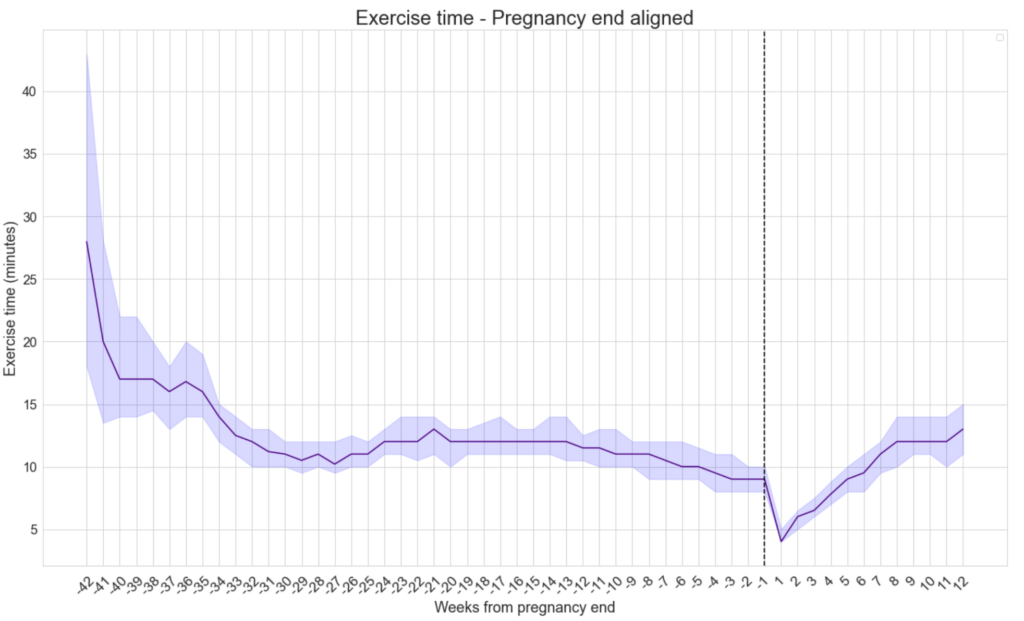

We were then able to describe the total number of exercise minutes recorded during workout sessions on the Apple Watch for participants before, during and after pregnancy (Figure 2). The image on the left is aligned on pregnancy start, which shows that while many participants are typically exercising 19 minutes per day (95% CI 16-21 minutes) before pregnancy, this decreases as the pregnancy progresses. When we align the data to focus on the date of delivery, we see that there is an expected decrease in total exercise minutes per day right around delivery, with a slow return to a median of 16 minutes per day (95% CI 11-15 minutes) by about 12 weeks after pregnancy among the people who responded.

Figures 2 & 3: Median and 95% CI of exercise minutes before pregnancy, during pregnancy, and after delivery in 757 pregnancies. The figure on the left is aligned by first day of last menstrual period as the pregnancy start and allows interpretation of exercise trends across pregnancy. The figure on the right is aligned by the delivery date for each pregnancy. Since each pregnancy ends at a different gestational age, the graphic on the right better represents exercise trends around delivery and postpartum. Participants needed at least 14 or more hours of Watch wear in a day, at least two days per week, for at least 90% of the weeks before, during and after pregnancy to be included.

How did resting heart rate change during and after pregnancy?

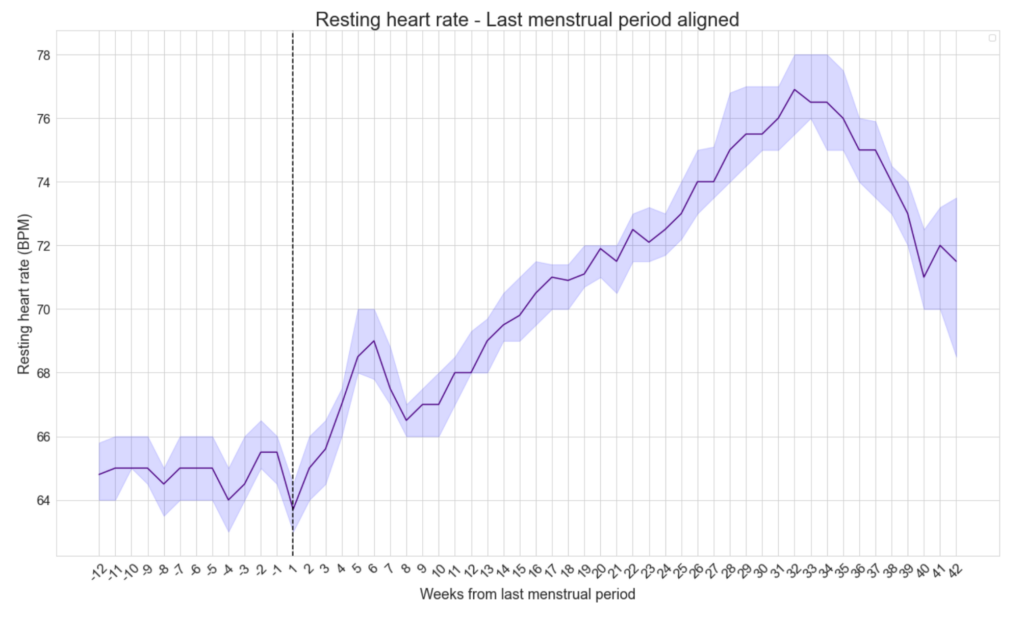

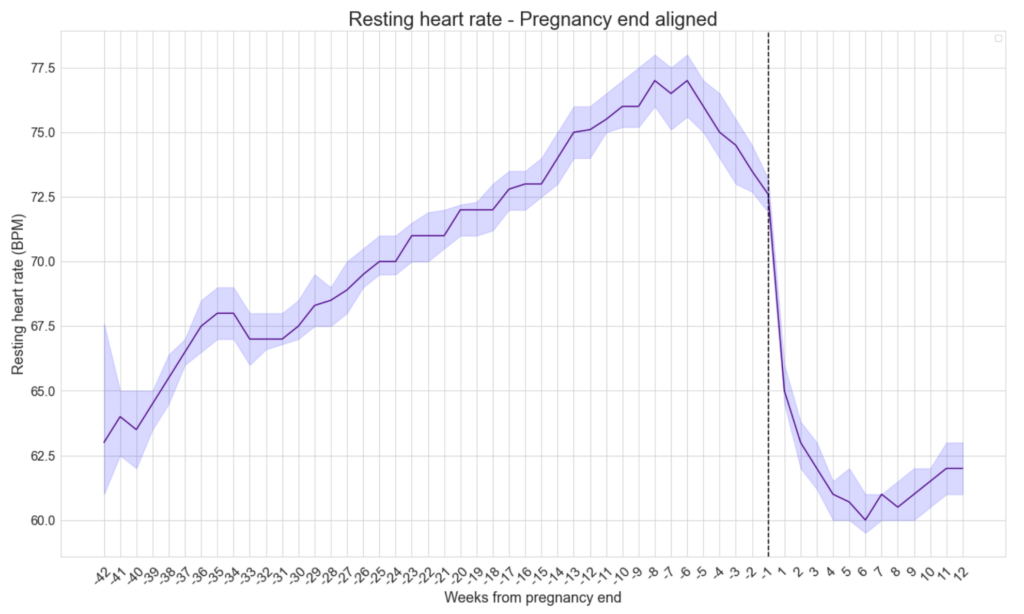

The median resting heart rate before pregnancy was 65.5 beats per minute (BPM) (95% CI 64.5-66 BPM). The resting heart rate increased during pregnancy, with a peak in the third trimester at 77 BPM (95% CI 75.8-78 BPM) around 8 weeks prior to pregnancy end. After delivery, there was a decrease in the resting heart rate (Figure 3).

Figures 4 & 5: Median and 95% CI of resting heart rate in beats per minute (BMP) before pregnancy, during pregnancy, and after delivery in 757 pregnancies. The figure on the left is aligned by first day of last menstrual period as the pregnancy start and allows interpretation of heart rate trends across pregnancy. The figure on the right is aligned by the delivery date for each pregnancy. Since each pregnancy ends at a different gestational age, the graphic on the right better represents resting heart rate around delivery and postpartum. Participants needed at least 10 or more hours of Watch wear in a day, at least two days per week, for at least 90% of the weeks before, during and after pregnancy to be included.

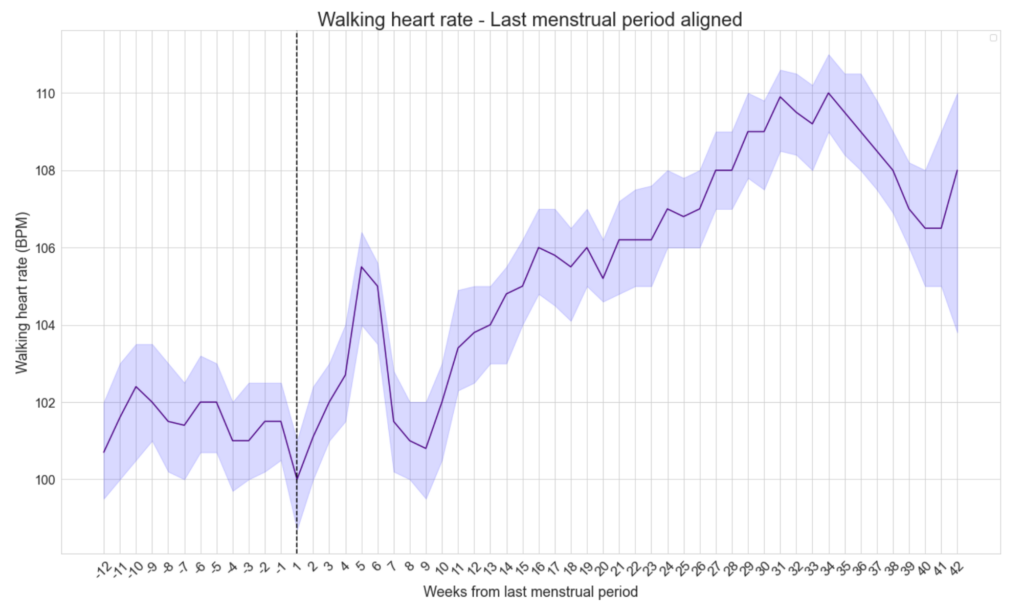

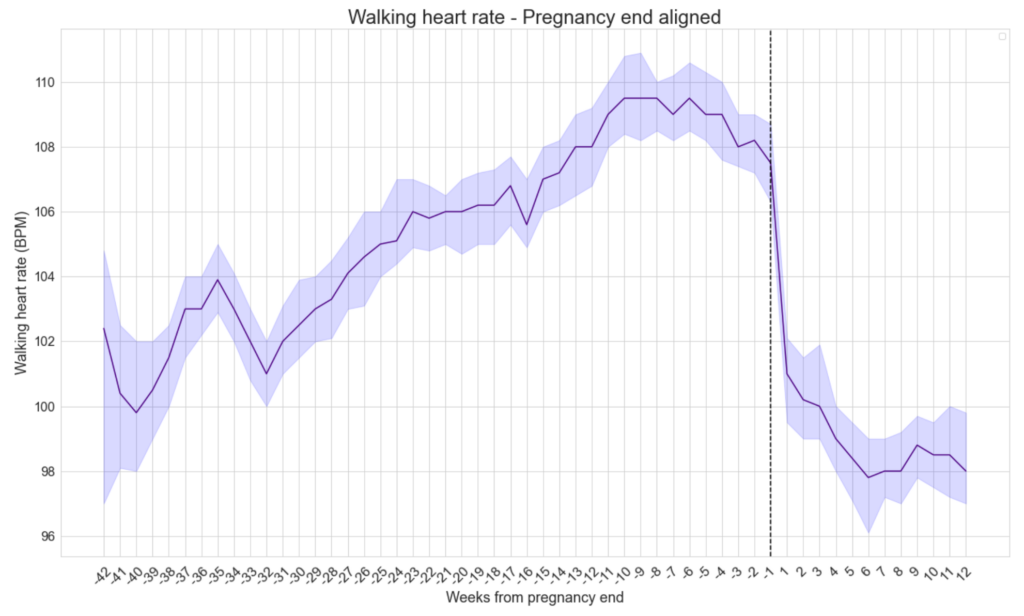

How did walking heart rate change during and after pregnancy?

Since walking is a commonly recommended form of exercise during pregnancy, we analyzed the heart rate when a participant was walking (Figure 4). The median walking heart rate before pregnancy was 101.5 BPM (95% CI 100-102.5 BPM). The walking heart rate increased during pregnancy, with a peak in the third trimester at 109.5 BPM (95% CI 108.4-110.7 BPM). After delivery, there was a decrease in the walking heart rate.

Figures 6 & 7: Median and 95% CI of walking heart rate in beats per minute (BMP) before pregnancy, during pregnancy, and after delivery in 757 pregnancies. The figure on the left is aligned by first day of last menstrual period as the pregnancy start, and allows interpretation of heart rate trends across pregnancy. The figure on the right is aligned by the delivery date for each pregnancy. Since each pregnancy ends at a different gestational age, the graphic on the right better represents walking heart rate around delivery and postpartum. Participants needed at least 10 or more hours of Watch wear in a day, at least two days per week, for at least 90% of the weeks before, during and after pregnancy to be included.

Conclusions

Physical activity is one of the most important things that people can do to improve health across the lifespan12. The recommendation to get at least 150 minutes a week of moderate intensity activity extends to those who are planning to get pregnant, are pregnant or are postpartum. For those who are able to exercise safely, movement and physical activity can be an important part of the prenatal and postpartum experience and may have benefits to both the pregnant person and the fetus. The reality is that finding time and feeling comfortable exercising may change as the pregnancy progresses and after delivery. Additionally, some people may have pregnancy complications that prevent safe exercise, or they may need to have a conversation with a care provider to help create an exercise plan.

In the Apple Women’s Health Study, while many participants continued to report exercise throughout the pregnancy and postpartum, they more frequently reported light or moderate activity, based on survey results. The overall changes in exercise minutes followed a similar course with decreasing exercise minutes per day in the third trimester and increasing exercise minutes by about three months after delivery. There were changes seen with the increase in resting heart rate throughout the pregnancy, as well as with an increase in heart rate when participants were exercising by walking.

Here we describe these trends so that those who are pregnant or are supporting someone through a pregnancy, have a better understanding of changes before, during, and after pregnancy. This analysis is not the same as medical advice; it is important that anyone who is pregnant talk with their care provider about how to safely get the benefits of exercise during and after pregnancy.

The Apple Women’s Health Study team is grateful to its participants for their continued contributions to public health research.

More information on Apple Research app & Privacy

- Exercise During Pregnancy.https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/exercise-during-pregnancy.

- Berghella V, Saccone G. Exercise in pregnancy! Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(4):335-337. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.023

- Barakat R, Pelaez M, Montejo R, Refoyo I, Coteron J. Exercise throughout pregnancy does not cause preterm delivery: a randomized, controlled trial. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11(5):1012-1017. doi:10.1123/jpah.2012-0344

- Owe KM, Nystad W, Skjaerven R, Stigum H, Bø K. Exercise during pregnancy and the gestational age distribution: a cohort study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(6):1067-1074. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182442fc9

- ACOG Exercise Recommendations. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/exercise-during-pregnancy

- CDC Healthy Pregnant or Postpartum Exercise Recommendations. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/pregnancy/index.htm#:~:text=Pregnant%20or%20postpartum%20women%20should,this%20activity%20throughout%20the%20week.

- Sarhaddi F, Azimi I, Axelin A, Niela-Vilen H, Liljeberg P, Rahmani AM. Trends in Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability During Pregnancy and the 3-Month Postpartum Period: Continuous Monitoring in a Free-living Context. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2022;10(6):e33458. doi:10.2196/33458

- Rowan SP, Lilly CL, Claydon EA, Wallace J, Merryman K. Monitoring one heart to help two: heart rate variability and resting heart rate using wearable technology in active women across the perinatal period. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):887. doi:10.1186/s12884-022-05183-z

- Loerup L, Pullon RM, Birks J, et al. Trends of blood pressure and heart rate in normal pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):167. doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1399-1

- Sanghavi M, Rutherford JD. Cardiovascular physiology of pregnancy. Circulation. 2014;130(12):1003-1008. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009029

- Brislane Á, Matenchuck BA, Skow RJ, Steinback CD, Davenport MH. Prenatal Exercise and Cardiovascular Health (PEACH) Study: impact of pregnancy and exercise on rating of perceived exertion during non-weight-bearing exercise. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab Physiol Appl Nutr Metab. 2022;47(7):804-809. doi:10.1139/apnm-2021-0691

- CDC Physical Activity for Different Groups. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/age-chart.html