Symposium explores health lessons learned from the pandemic

November 3, 2021 – What lessons have scientific researchers learned from the COVID-19 pandemic? And how can they better apply them to the next major outbreak of disease? More than 200 participants gathered virtually to discuss those questions at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s 24th annual John B. Little Symposium, held on October 29, 2021.

The event honors the late John B. Little, who was the James Stevens Simmons Professor of Radiobiology Emeritus in Harvard Chan School’s Department of Molecular Metabolism. Little passed away in May 2020.

“I vividly remember Jack always sat in the front row with undivided attention,” said Zhi-Min Yuan, Morningside Professor of Radiobiology and director of the John B. Little Center for Radiation Sciences, who moderated the symposium. “Jack’s ongoing legacy stays with us, as we continue this highly received annual event.”

In her opening remarks, Dean Michelle Williams introduced the theme of this year’s conference, “COVID-19: Transformative Discoveries and Emerging Research Frontiers.” Said Williams, “Just as our personal lives have been upended for the past 20 months, so have been the professional lives of researchers. This disruption required really remarkable, profound adaptations that gave rise to new ideas.” The diverse group of speakers for the symposium, she noted, shared a wide range of perspectives, including from molecular biology, epidemiological studies, and translational studies.

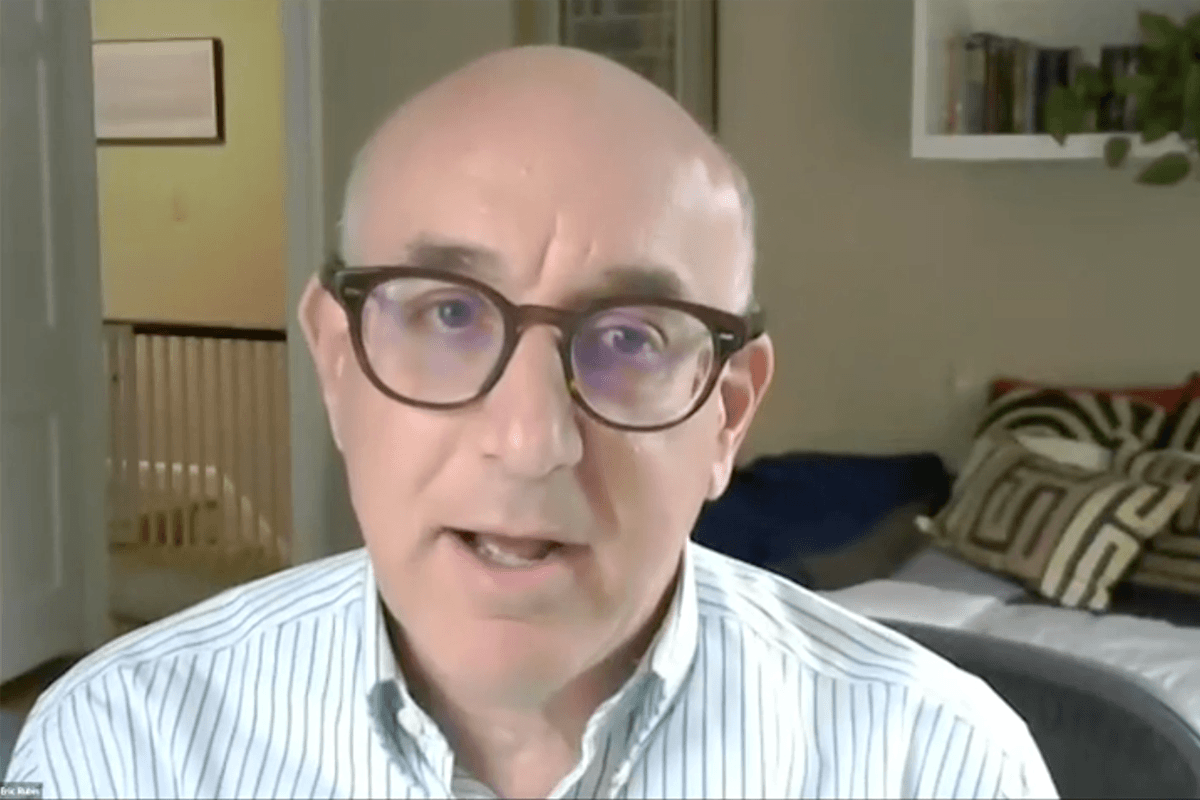

Among them was Eric Rubin, editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine and adjunct professor of immunology and infectious diseases at Harvard Chan School, who spoke on the difficulties of generating accurate data for treatment of COVID-19 in the early days of the pandemic. While as a clinician, Rubin said, he could understand the desire for clinicians to try some kind of therapy to address patients’ suffering, they often drew the wrong conclusions from incomplete early studies. He noted that hydroxychloroquine was widely used “before it was shown to do nothing,” remdesivir was widely used despite a “very mild effect if any,” and dexamethasone was virtually ignored. “And that is one that worked!” he said.

Very few of the millions of patients suffering from COVID-19 were involved in clinical studies, Rubin added, and many of the studies conducted during the pandemic were done on small groups of patients without coordination with one another. In the future, Rubin said, researchers must get better at leveraging existing infrastructure for clinical trials to coordinate studies much more rapidly. “It’s really important, even in the midst of an epidemic, to figure out whether or not what you are going to do is going to answer the question you care about,” he said.

Other speakers at the symposium included the National Institutes of Health’s Michele Evans, who spoke on health disparities during the pandemic; University of Iowa microbiology and immunology professor Stanley Perlman, who discussed breakthroughs on animal models for COVID-19; and University of Texas at Austin molecular biosciences professor Jason McLellan, who detailed techniques for identifying the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein that allowed for rapid development of vaccines.