Studio event on new musical explores ways to combat childhood bullying

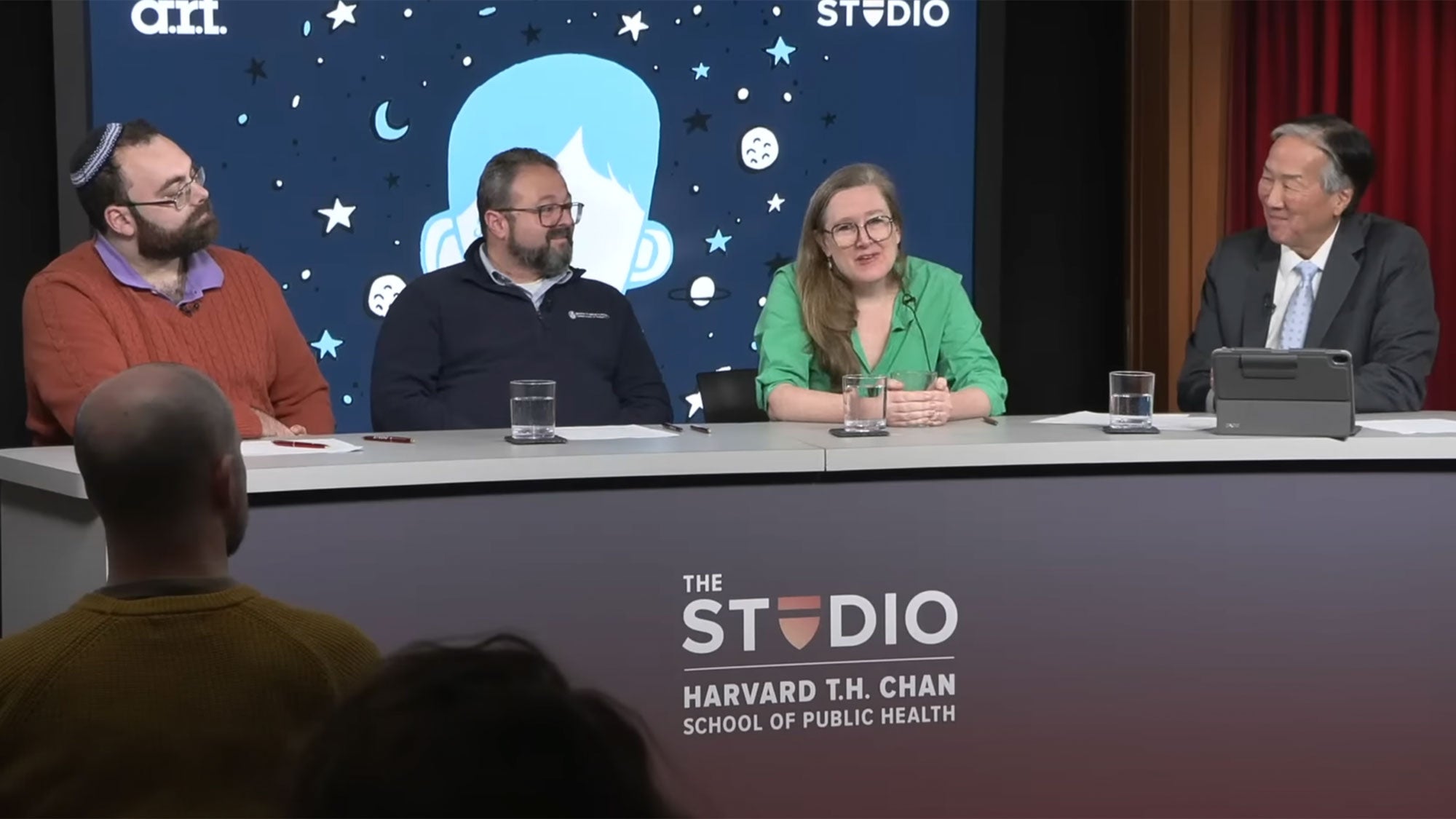

The negative impact of bullying on children’s health, and strategies for reducing stigma against people with disabilities, were explored during a Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Studio event on Dec. 4. It was presented jointly with the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.) in conjunction with the premiere of the new musical “Wonder” on Dec. 10.

“Wonder”—based on the children’s novel by R. J. Palacio and its 2017 film adaptation—tells the story of Auggie, a 10-year-old boy with Treacher Collins syndrome, a genetic condition that causes significant facial differences. As Auggie navigates a new school and experiences bullying, the musical weaves in themes of resilience and cultivating compassion.

The Studio event, which was moderated by Howard Koh, Harvey V. Fineberg Professor of the Practice of Public Health Leadership, featured videos of two songs from “Wonder,” composed by Ian Axel and Chad King, during the panel discussion.

Pursuing inclusion, compassion

“Wonder” playwright Sarah Ruhl said that both on-stage and backstage, the musical has been shaped by the experiences of members of the disability community who served as advisers, creators, and performers. The young actors who portray Auggie have facial differences, and the A.R.T. has been very intentional about creating an inclusive and compassionate environment, she said.

Ruhl said she believes culture can change attitudes, noting that she had heard from a nurse who works with children with craniofacial differences that her patients experienced less bullying at school after the book came out. Ruhl said that she would like to see more fictional stories that celebrate compassion and kindness rather than violence, and that theater can be an especially effective vehicle for promoting empathy.

While narrative can be valuable for reducing stigma, it can also inadvertently reinforce it, said panelist Ari Ne’eman, assistant professor of health policy and management. In a respectful critique of the musical, he said that he felt that Auggie had less agency and narrative arc in the story than his family members. He said, “Disabled people very frequently are presented as objects of inspiration or charity whose primary narrative function in art and media is their impact on the non-disabled people around them.”

Ne’eman, who is autistic, also stressed that challenges people with disabilities face are not simply due to a lack of compassion but rather long-standing prejudice embedded in society. He called for greater enforcement of civil rights laws, and for public policies that promote greater inclusion in schools and workplaces and expand access to home and community-based services. He sees these steps as critical for reducing stigma. “I think social change follows from getting people interacting with disabled people in day-to-day life on equal terms,” he said.

A public health problem

While many people may think of bullying as an unpleasant but normal rite of passage, it is actually a serious public health problem, said panelist Jason Fogler, a Harvard Chan School instructor and a psychologist based at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. He noted that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recognizes bullying as an adverse childhood experience—a type of trauma that can have long-term negative effects on health and well-being. “Bullying is every bit as toxic as neglect, as abuse, as having an incarcerated family member,” he said.

Fogler discussed multiple approaches for tackling bullying. Massachusetts was the first state to enact an anti-bullying law, he noted. He also said that “upstander” trainings, which empower people to take action against mistreatment in their schools and workplaces rather than simply being a bystander, have been shown to be effective.

When asked what parents can do if they suspect their child is being bullied, he said to watch for uncharacteristic changes in behavior. “Grades start slipping. There’s reluctance to go to school. There’s dragging feet getting out the door. Things they used to enjoy, they don’t enjoy anymore. Kids that they used to want to spend time with, they don’t want to anymore,” he said. That’s the time to ask, “Hey, what’s going on?” he said.