Student Perspective: My lessons in vulnerability

In July 1991, I found myself sitting in the back seat of our family car, heart pounding with a mix of excitement and apprehension.

The 10-day war for Slovenian independence from Yugoslavia had just ended, and while the armed conflict was officially over, the atmosphere was still thick with uncertainty. The weeks prior had been marked by listening to press conferences of the national war cabinet and evacuating hurriedly to bomb shelters. I remember the fear that gripped me as both my parents left for work each day—my mother to care for patients at the regional hospital, and my father, a first responder, on site to protect a key factory from potential bombings that could lead to deadly chemical spills.

It was against this backdrop that my parents were now driving me to Villach, Austria, where I was to attend a four-week immersive German language course. This was something I had been looking forward to all year—a chance to brush up on my German before entering my freshman year of secondary school where I’d study it as the second foreign language.

But as we crossed the border, the thrill of the upcoming adventure was tinged with a new, deeper sense of fear.

When we arrived in Villach, my parents helped me settle in, and then it was time for them to leave. As we stood outside the small dormitory where I would be staying, my mother turned to me with a seriousness I hadn’t seen in her before. “If the war breaks out again,” she said, her voice steady but her eyes betraying a deep worry, “don’t try to come back to Slovenia. Stay here in Austria and find a way to your uncle in Sweden.” I nodded, the gravity of her words sinking in. Suddenly, the world seemed much larger, and far less certain, than it had just moments before. Despite the bombing scares and evacuations I had endured during the brief war, it was in that moment, hearing my mother’s words, that I felt the most afraid. I realized that if conflict erupted again, I would be on my own as a 14-year-old girl in a foreign country.

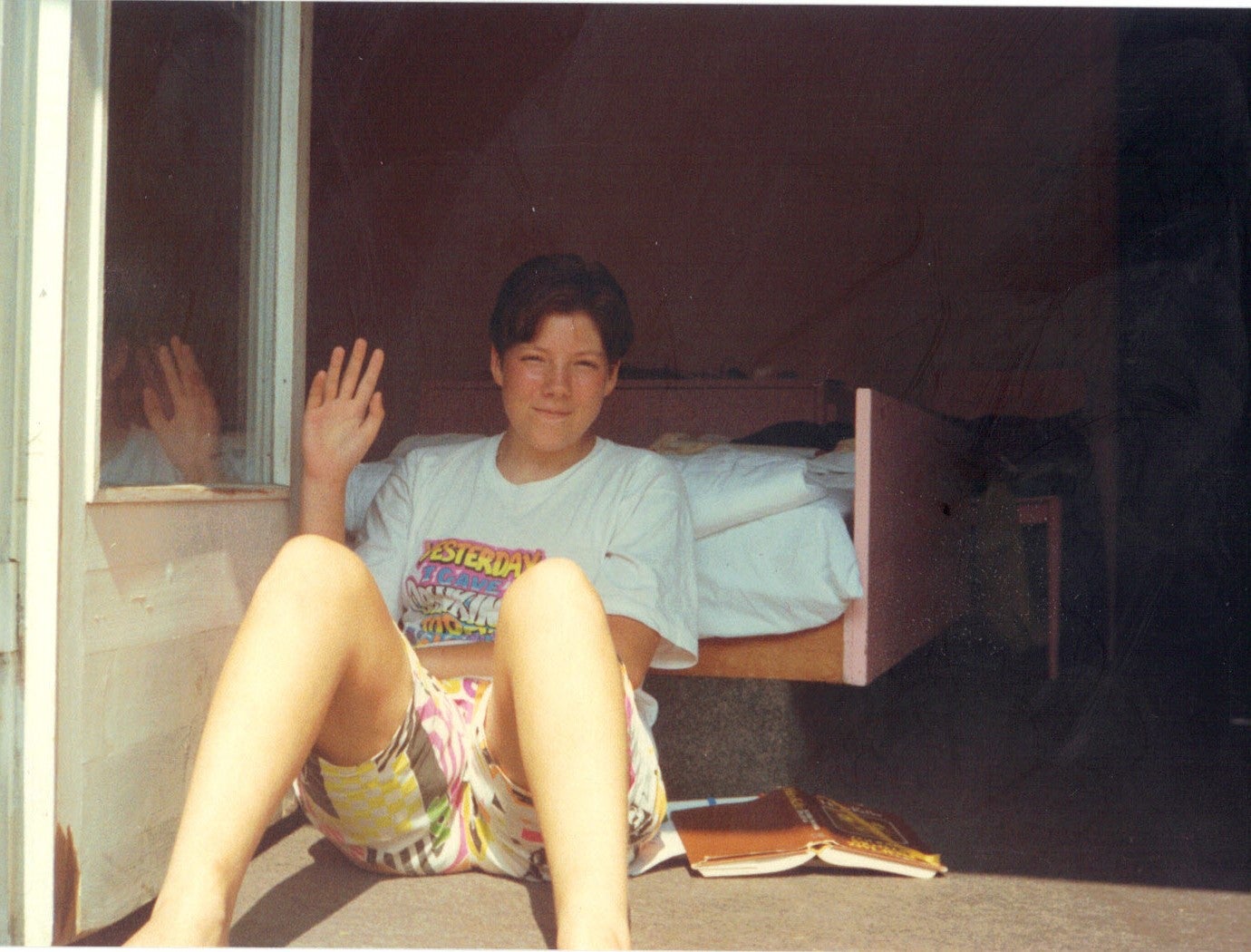

For the next four weeks, I was surrounded by other teenagers from Slovenia and various other parts of Europe. We spent our days conjugating verbs, practicing vocabulary, swimming, hiking and navigating the cultural quirks of our peers. But in the back of my mind, my mother’s words lingered. What would happen if the conflict reignited? How would I make my way to Sweden on my own? How would I even find my uncle there? The thought of being stranded in a foreign country, unable to return home, was terrifying. It was my first real encounter with the vulnerability that so many people around the world experience daily—the fear of being uprooted, of losing the safety of home.

Thankfully, the weeks passed without incident. No more armed conflict erupted in Slovenia, and my parents returned to pick me up as planned. But I was not the same person who had arrived in Villach just four weeks earlier. The experience had left an indelible mark on me, a heightened awareness of the fragility of safety and the ever-present possibility of displacement.

Back in Slovenia, I couldn’t shake the thoughts of what might have been. I imagined what it would be like to be forced to flee my home, to live in a place where I didn’t speak the language, surrounded by people who didn’t understand my culture. These thoughts only grew stronger in the following weeks and months as the war in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina intensified. Refugees were fleeing their homes, seeking safety wherever they could find it, and often first in Slovenia before moving on to other countries. Many of them were children, just like me, whose lives had been upended overnight.

Later on, I decided to volunteer as a companion and homework tutor for kids my own age at the refugee center. It wasn’t just about helping them with English homework and math; it was about being there for them, offering some semblance of normalcy in their otherwise chaotic lives.

I remember a brother and sister, both in their early teens, who never left each other’s side. I remember thinking: we grew up in the same federation of Yugoslavia, just in different parts of it, and just because of where we were born, I had a home but they lost it. Despite their reserved demeanor, I made it my goal to connect with them. I would bring bubble gum and comic books to our meetups, hoping to break the ice. At first, our interactions were limited to simple exchanges—sharing a piece of gum, pointing out a favorite comic strip. But over time, these small gestures began to build a bond between us.

We never talked about the war or their experiences—those topics remained unspoken, heavy in the background. But through our shared love of comic books and the simple pleasure of chewing gum, we found a way to connect. They would smile, sometimes even laugh, and in those moments, I knew I was making a difference, however small. We communicated in the language of teen friendship, where words were less important than the shared experiences that brought us a bit of lightheartedness in a difficult time.

Then, one day, they were gone—moved on to Germany for asylum. I never got to say goodbye, but I like to think that our time together left a positive mark on their lives, just as it did on mine. I often wonder where they ended up—Canada? The U.S.? New Zealand? Sweden? Maybe they ended up settling in Germany? Wherever they are, I hope they remember those afternoons spent laughing over comic books and enjoying the small pleasures of pink bubble gum.

These experiences shaped my understanding of vulnerability in profound ways. They led me to the profession of public health because public health, at its core, prioritizes the needs of the most vulnerable and at-risk populations. It emphasizes the values I learned from my parents and wider family—the importance of empathy, service, and resilience. My time with those refugee kids taught me that vulnerability is not just about addressing immediate needs but also about the layers of crises people experience and endure, often silently. Public health approaches cannot solve all their problems, but working in this field gives me a tangible way to address some of the critical needs of people who, like those refugee kids, experience and navigate multiple crises. It’s about creating systems, structures and solutions that support their resilience, help them find stability, and, ultimately, help them to rebuild their lives and thrive.

Thirty-five years later, I’ve built a career in public health. The responsibility to serve and protect the most vulnerable remains at the forefront of everything I do. Whether I’m working with health information and evidence, implementing digital health solutions, combating health misinformation, pointing out deceptive marketing of vapes to youth, or responding to outbreaks, it’s never just about the policy, tools, data or the technology. It’s always about the people—the children, the families, the communities—who need health systems and public health efforts to better serve them and meet their needs.

Returning to that summer in Villach, I realize now that it was a turning point in my life. The uncertainty I faced then is minute compared to the struggles of those who live in conflict zones or walk thousands of miles in search of a safer home, but it gave me a window into their experience. It taught me that the safety and stability I had always taken for granted could be lost in an instant, and that those who are forced to flee their homes or are displaced within their own country or even within their own city need more than just shelter and services—they need understanding, compassion, and a sense of belonging.

As I continue my work in public health, I carry these lessons with me. My mother’s words, spoken with such quiet urgency, have stayed with me, reminding me of the responsibility we all share to protect the vulnerable.

And every time I meet someone who has been displaced, I think back to that 14-year-old girl in Villach, standing alone in a foreign country, and I know that I am doing what I am meant to be doing—helping to build a world where no one has to face that kind of uncertainty alone.

—Tina Purnat is a DrPH student and Prajna Leadership Fellow.