Preparing for next pandemic requires more funding, better communication

Over the past few months, Harvard Chan faculty have been sharing evidence-based recommendations on urgent public health issues facing the next U.S. administration. Kizzmekia Corbett-Helaire, assistant professor of immunology and infectious diseases, offered her thoughts on preparing for the next pandemic, including the need for additional funding, clearer communication from public health leaders, and stronger partnerships among government agencies, business, and academia.

Q: Why is pandemic preparedness a pressing public health issue?

A: The COVID-19 pandemic exemplifies why preparing for the next pandemic is a pressing issue—and it’s just the tip of the iceberg.

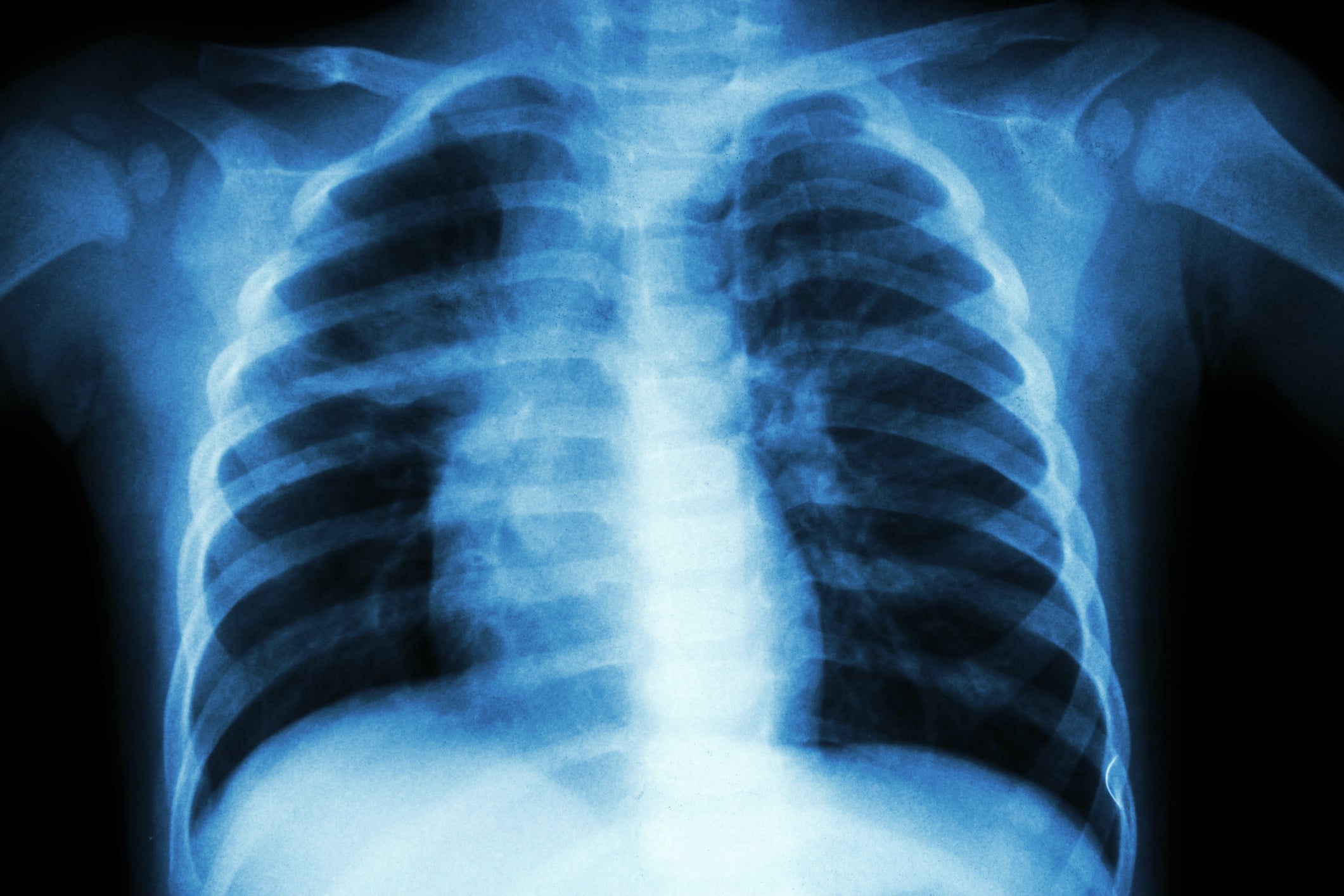

There are 26 viral families with the ability to infect humans, which could therefore cause a pandemic. For many of these families, we have far less knowledge and understanding than we did of coronaviruses before the COVID-19 pandemic. That means we’re starting with less infrastructure and tools to confront an outbreak or a potential pandemic. That is a dire public health concern, and one we should tackle before crisis strikes.

Q: What are the biggest challenges that the next administration faces around pandemic preparedness?

A: There are a few—but the biggest challenge by far is a lack of funding. The prioritization of funding toward pandemic preparedness is a major obstacle, because it can be hard to get leaders to allocate significant resources toward things that might happen.

The fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic is an obstacle to long-term funding. I know that many people are unconsciously dealing with a level of avoidance, craving normalcy rather than mustering enthusiasm to confront another potential challenge to our collective health and well-being. It’s a human desire to seek comfort and safety, but if we let that desire prevent us from preparing for the next pandemic, the cost will be extreme.

Another key challenge is that preventing a pandemic isn’t something the government can do alone. To be most effective, the government should be building and strengthening partnerships with private companies and academic institutions, as we did during the pandemic. These outside organizations can provide funding, equipment, and talent needed to pursue this work and ensure best results. The challenge, of course, is that the government cannot fully direct the activities of these companies or schools—but even still, the benefits are significant.

Q: What are your top policy recommendations to support pandemic preparedness?

A: We saw how much money we could muster into pandemic preparedness during the COVID-19 pandemic, but providing a baseline level of funding in quieter times is critical. One proposal, which would cost a few billion dollars per year, would tackle many of the underfunded and understudied viral families and help build a solid scientific foundation that we can build off for future pandemics. That seems like a lot of money—until we need that knowledge. The cost of starting up a process in the middle of an emergency is far more than building from existing research.

We also need to revisit the current ways that the government does, or quite frankly even does not, communicate around outbreaks. We as scientists think a lot about how we can prepare and research new vaccines or other public health measures, but we don’t devote enough time to thinking about how to prepare the general public. There’s a benefit to having pandemic preparedness be an ongoing conversation, so when emergencies arise the public is ready to respond.

I think that we also need to get policies in place around sick leave, which is not guaranteed in this country. The federal government should provide emergency funding for people when they’re out sick so that the public knows that we value them. We value their time, we value their health, we value their lives. Paid sick leave would help reduce spread and make sure that people aren’t choosing between risking their own lives—or the lives of those around them—or missing a paycheck that keeps a roof over their head and food on the table.

Q: What’s the evidence supporting those recommendations?

A: The evidence relating to most of these recommendations has played out in front of our eyes throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our vaccine efforts benefited significantly from previous research into the field, which yielded knowledge bases that could be utilized by researchers involved with Project Warp Speed, the federal effort to accelerate COVID-19 vaccine development. However, that level of early research is lacking for many viral families; we should make up those shortfalls while we can.

The value of clear and consistent communication also became clear throughout the pandemic. A study led by my Harvard Chan School colleague Gillian SteelFisher found that people’s faith in public health institutions was significantly impacted by whether they felt that leaders led with clear, evidence-based recommendations. On the other hand, trust was harmed by conflicting recommendations or proposals that appeared to be politically influenced. By proactively establishing pandemic response guidelines before crisis strikes, we can help the public recognize that forethought and experience are guiding our decision making.

As for sick leave: The United States is one of the few high-income nations that does not mandate any form of sick leave for workers, despite studies showing that sick leave improves not only employee health, but also morale, productivity, and attendance. Sick leave protections were instituted during the pandemic but lapsed at the end of 2020. Bringing those protections back are common-sense fixes that will support both pandemic preparedness and overall public health.

Q: What do you hope could be accomplished to improve our ability to prevent and/or respond to pandemic threats in the next four years?

A: The best-case scenario is that we have a consistent funding stream that focuses specifically on science for pandemic preparedness, as well as an overhaul of public health measures for pandemic preparedness.

Our targets should include:

- Some level of indoor air quality control regulation.

- Solid policies around pandemic response, complete with thresholds of what markers must be hit to enact actions ranging from masking to social distancing.

- Communicating these policies to the public in advance, so they understand that we are operating from a place of science rather than fear. That includes reviewing our approach around vaccine and vaccine uptake, so we can build trust with communities on the safety of vaccines without turning recommendations into law.

One key metric I’ll use to judge the country’s pandemic preparedness at the end of the next administration is how it approaches flu seasons. How is our flu vaccine uptake? How about our funding, wastewater surveillance, projected deaths? Do hospitals have systems in place to ensure that overcrowding isn’t a concern?

These are longstanding challenges, but they are indicative of the strength of our public health infrastructure’s ability to confront infectious diseases. If we can build systems to handle the flu, then we will be able to rely on those systems to confront future infectious disease pandemics.