The power of global partnerships in public health

May 25, 2022 – Solving global public health problems such as climate change or a pandemic will require partnerships of all kinds, according to Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Jane Kim.

Kim, dean for academic affairs and K.T. Li Professor of Health Economics, spoke at the School’s Convocation for the Class of 2022 at the Reggie Lewis Center in Roxbury Crossing on May 25, 2022. “It’s up to you to make sure that what we’ve learned in this pandemic isn’t quickly forgotten,” she said. “That your work isn’t confined to disciplines or sectors or borders. That you seek out and invest in ideas from all over the world.”

The ceremony—the first in-person graduation to be held since 2019 due to the COVID-19 pandemic—celebrated the accomplishments of 633 graduates. Degrees, which will be officially granted at the Harvard Commencement ceremony on May 26, included doctor of philosophy (60), doctor of public health (9), doctor of science (1), master in health care management (25), master of public health (387), and master of science (151). Forty percent of the graduates came from outside the U.S., from 46 different countries.

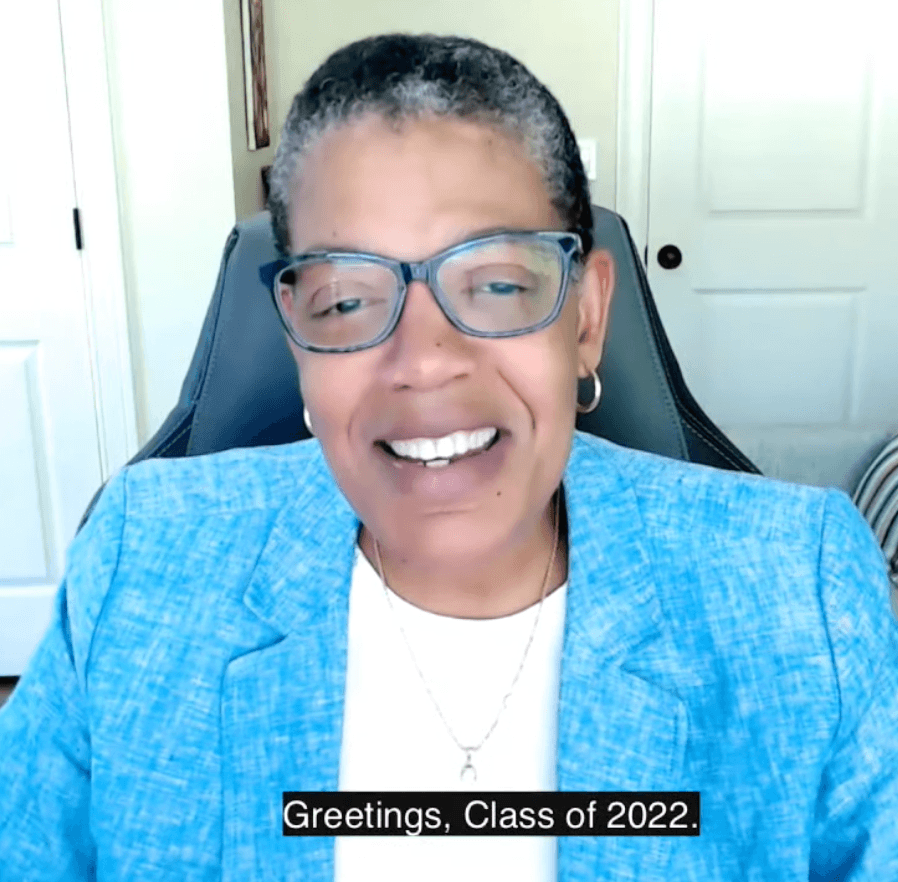

Dean Michelle Williams, who was unable to attend the ceremony due to testing positive for COVID-19, offered remarks via video. “I’m feeling much better—but I certainly would not want to flout public health guidelines in front of hundreds of future public health leaders!” she said.

Williams thanked the graduates for “jumping in headfirst during the most daunting public health crisis of your young lives.”

“You could easily have given up your spot here to focus on your sourdough starters, or waited a few years until Zoom classes were a thing of the past,” she said. “But instead, you chose to respond to the urgency of the moment.”

In addition to Williams and Kim, speakers at the ceremony included student speaker Sumantra Monty Ghosh, MPH ’22; graduation speaker Mamphela Ramphele, an activist, medical doctor, academic, business leader, and political thought leader; and Trishan Panch, president of the Harvard Chan School Alumni Association.

Also at the ceremony, Erin Driver-Linn, dean for education, announced the annual awards for graduating students, faculty, and staff, including the winners of the inaugural Sastry Awards.

‘Public health is global health’

Kim acknowledged that “it might feel incongruous to celebrate in the midst of a global pandemic” and that it’s hard not to feel overwhelmed by the many public health crises in the world.

“I know our hearts grow heavy when we think of the senseless shootings yesterday at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, and earlier this month at Tops Supermarket in Buffalo, New York, and the Taiwanese Presbyterian church in Laguna Woods, California,” she said. “Gun violence is surely among the top public health issues that we collectively must face.”

But she added that her overriding emotion was one of optimism. “I’m optimistic because I know that all of you will be a driving force—an unstoppable force—in building a healthier and better world for everyone,” she said.

Kim spoke about Paul Farmer, the pioneering global health physician and medical anthropologist who died in February. As chief strategist of the international health organization Partners in Health, Farmer worked to improve health care for some of the most vulnerable people in the world, in places like Haiti, Sierra Leone, and the Navajo Nation, she noted.

She quoted Farmer’s words from a graduation speech he gave in 2012: “‘With rare exceptions,’ he said, ‘All of your most important achievements on this planet will come from working with others—or, in a word, partnership.’ Ten years and one pandemic later, his message still resonates deeply. If COVID-19 has taught us one thing, it is that public health is global health.”

As an example of the importance of taking a more global approach to problem solving, Kim cited the discovery of the omicron variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in Gaborone, Botswana. Sikhulile Moyo, director of the Botswana-Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership lab, noticed an unusual pattern while sequencing COVID samples in mid-November, and shared his findings with colleagues in South Africa, who also found the new sequence. The researchers alerted the rest of the world about the new, highly contagious variant was on the move.

“Now, just imagine what would be possible if that kind of international public health partnership was the rule and not the exception,” she said, adding, “What we do—and whether we do it together—will set the course for human health for the next century and beyond.”

A call for innovation to improve equity

Ghosh is a medical doctor on the faculty of both the University of Alberta and the University of Calgary in Canada who focuses on substance use disorders, harm reductions, and populations experiencing homelessness. He began his remarks by noting that he’d taken a COVID-19 test that morning. He held up a test kit, marveling at its invention, but noted that, “at $20, it is likely affordable for most of us Harvard grads, but its price tag is out of reach for many.”

He spoke about one of his patients, Sandy, who lives in a shelter and for whom $20 “would be the difference between a reasonable meal or rummaging through scraps.” When there was a COVID-19 outbreak in the shelter, Sandy chose to sleep outdoors, even though there was a cold snap. “A week after, he came to show me his blackened toes, frostbit and numb,” Ghosh said. “The look in Sandy’s eyes told me he knew he would lose his toes. But, seeing the gangrene creeping up to his ankles, I knew he would lose his feet.” He added, “While the world responded to COVID with brilliant solutions at a breathtaking pace, it left Sandy behind, where his inequity literally jeopardized life and limb.”

Ghosh acknowledged that numerous innovations have brought greater equity to the world. For example, telehealth helps people from having to take off unpaid leave from work to see a doctor, and mail-in kits allow those in rural communities to screen for colon cancer without driving long distances for a screening.

But some say that while innovation has generated equity, it has often been unintentional because the motive behind it was profit, Ghosh said. “We failed to innovate around the principles of social justice and economic equity,” he said. “Where was the innovation to protect those who could not physically distance while working in factories and meatpacking plants? What innovations could have spared Sandy the horrible choice between COVID and his feet?”

Harvard Chan School’s new graduates can help change the narrative, Ghosh said, noting, “Innovation must be driven with the philosophy of improving equity, not an accidental by-product of it.”

Liberating the self, shaping the future

Ramphele was a co-founder, with Steve Biko, of the Black Consciousness Movement that reignited the struggle for freedom in South Africa. She is co-president of The Club of Rome, a global coalition that promotes holistic solutions to planetary threats; and is a co-founder of ReimagineSA, which works in South Africa toward systemic change across multiple domains that intersect with public health.

The human race itself is responsible for “the multiple planetary emergencies we are experiencing,” including COVID-19 and climate change, Ramphele told the graduates. “The world has received and will continue to receive harsh lessons from Mother Nature about the interconnectedness and interdependence of everything with everything else in the web of life,” she said.

She noted that science has clearly demonstrated a causal link between climate change and humanity’s patterns of over-consumption. And pandemics, she said, “are signifiers of broken sacred barriers between us and zoonotic pathogens in our biosphere. We are increasingly encroaching on ecosystems not habitable for humans.”

Ramphele talked about how she and other student activists of the 1960s were inspired to think about the importance of “self-liberation” by Frantz Fanon, an Algerian psychiatrist. “He helped us understand the importance of liberating the self from inferiority complexes imposed by racist supremacists as a prerequisite to becoming high-impact leaders,” she said. “We came to understand that mental slavery is more powerful than physical slavery because its victims come to believe that they deserve no better than oppression. He helped us to embrace our authentic selves as Black and proud free agents of the change we wanted to see in the world.”

She said that both her country, South Africa, and the U.S. have yet to sufficiently acknowledge the “wounds and scars of our violent historical legacies: slavery, racism, sexism, and other chauvinisms that are embedded in our nations’ psyches.” Both countries, she added, are in need of “national healing processes to liberate the inner persons in each and every one of us to become fully whom we were created to become—free people able to shape the future we aspire to.”

The most important resource in the public health toolkit—people

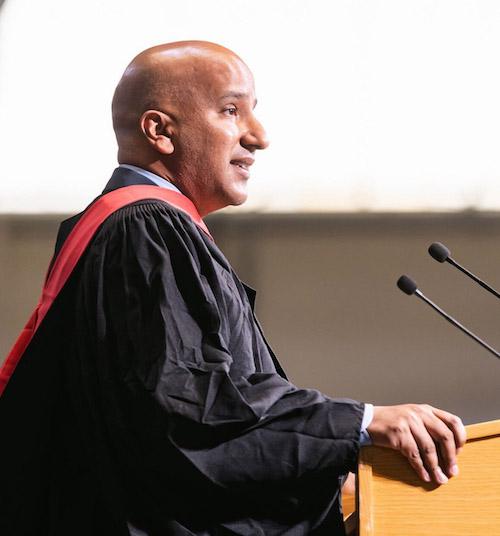

Panch—co-founder of Wellframe, a digital health company that uses technology to improve chronic disease management—acknowledged the many challenges in public health, including addressing multimorbidity and aging, structural and physical violence, and climate change; cultivating wellbeing and nutrition; and conquering pandemics.

“Though these challenges are broad and deep, there have never been more tools to address these issues, from machine learning to a new science of teamwork,” he said. “And yet the most important resource in the public health toolkit remains its people—you.”

photos:

Kent Dayton, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

J.D. Levine

Ben Gebo Photography

Additional coverage

Watch video of Harvard Chan School’s 2022 graduation

Graduation 2022: Award winners

Jesse Bump, Nancy Turnbull receive inaugural Sastry Awards for outstanding teaching

Graduation 2022: A day of reconnecting and learning

Graduation 2022: At Affinity Graduations, students can celebrate ‘in community with others on a shared experience’

Photo gallery – Class of 2022 (password: 2022)