Breaking Breakbone Fever

A Harvard Chan School alumnus and a DrPH student are developing strategies for bringing a dengue vaccine to countries in need.

By Amy Roeder

In September 2016 at Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital in New Delhi, India, a woman receives treatment at a clinic for people suffering from fever, one of the main symptoms of several endemic mosquito-borne infections. Despite spraying vast areas with clouds of diesel smoke and insecticide, several Indian cities battle dengue fever, chikungunya, and other mosquito-borne diseases every year. AP Photo / Manish Swarup

Sana Mostaghim, DrPH ’18, used to think of mosquitoes as mere annoyances. Growing up near a ski resort in the city of Kamloops, British Columbia, he never had to worry about more than an itchy bite. But while working at the Clinton Health Access Initiative in New Delhi, India, in 2010, his eyes were opened to mosquitoes’ ability to inflict grave harm.

The dengue virus, spread primarily by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, surges during India’s rainy summers, and that year was particularly bad. New Delhi saw 1,695 cases, including a relative of one of Mostaghim’s colleagues, who developed a severe form of the disease. An outbreak in 2015 was even worse. According to news reports people panicked, and even many with mild symptoms demanded blood transfusions from the city’s already overtaxed hospitals, where they crowded sometimes two or three to a bed.

In countries like India, where the mosquito-borne infections dengue, malaria, and chikungunya are endemic, the threat of a bite is ever-present, Mostaghim says. “Any mosquito you see could be the unlucky one. If you think about it too much, it’s overwhelming.”

Dengue thrives in poverty, where inadequate drinking water, sanitation, and surface water drainage promote mosquito breeding sites. While most people survive dengue with treatment (see below), the economic consequences can be devastating for those already living precarious lives. Taking time off to recover or to care for a sick child can mean lost wages and no food on the table.

And when the disease kills, it doesn’t discriminate, as the death of a Bollywood filmmaker in 2012 drove home. A New Delhi father told Al-Jazeera at the time, “I fear for my children more from a mosquito than any terrorist attack.”

Today, Mostaghim is in a position to help ease some of that anxiety. As associate director of global market access for vaccines at Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, he’s helping lay the groundwork for the company’s planned rollout of its dengue vaccine candidate, TAK-003. It has not yet been licensed and is still undergoing safety and efficacy trials, but the company hopes to offer it soon, building on clinical trials underway in eight Asian and Latin American countries ravaged by the disease.

Kindred spirits from the front lines

Mostaghim joined Takeda last year for his DELTA Project—the culminating work experience for the DrPH degree at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health—and was then hired full time. On DELTA Projects, students engage in a work experience of at least eight months, usually with a host organization. The aim is not only to conduct thesis research and build front-line skills but also to make a substantive contribution to public health. Mostaghim so impressed his colleagues at Takeda that he paved the way for future DrPH students at the company, starting with Elvis Garcia, MPH ’16, DrPH ’19, who is now in the midst of his DELTA Project.

Open and friendly, with a wide-ranging curiosity, Garcia has spent the past few months getting to know Takeda’s global vaccine unit at every level, meeting with everyone from bench scientists to regulatory specialists, all of whom are located in the same Cambridge, Massachusetts, campus. It’s a place he never thought he’d be.

Originally from Pola de Lena, a small village in northern Spain, Garcia describes his background as “hardcore humanitarian.” Before coming to the Harvard Chan School, he worked for a decade with Doctors Without Borders, with most of those years spent on the front lines of public health crises. He led a team that collected the bodies of Ebola victims in Liberia, assisted in the humanitarian response for refugees in Darfur, and ran vaccination campaigns in countries including Chad and the Central African Republic. And he is well-acquainted with the devastating consequences of mosquito-borne infections.

“I worked on a malaria project in the Central African Republic where we had 500 to 600 children a week coming to the clinic. Many of them died,” he says. “Nothing we could do was enough. I felt like we were putting out fires with a water gun.”

Garcia’s experiences in the field left him with little patience for global health interventions that look good on paper but fail to comprehend realities on the ground. He has co-authored papers identifying gaps in the global response to infectious-disease epidemics, such as poor pathogen surveillance and clinical information sharing.

But failing to understand cultural norms, he says, is also a major stumbling block. During the 2013–2016 West Africa Ebola epidemic, for example, some humanitarian responders struggled to establish trust with people who favored traditional healers and harbored suspicions about the international community. They were not able to convince residents that local burial customs that brought family members into direct contact with the bodies of highly contagious victims would spread the disease.

When people in the West design global health interventions, they sometimes fail to understand the lives of the people they’re trying to help, Garcia says. He found a kindred spirit in Mostaghim—who comes across as more reserved than Garcia but no less passionate about improving access to vaccines.

“I’ve been extremely fortunate to have Sana here, not just to ease my transition to the private sector but to help me understand how the pharmaceutical industry works,” Garcia says. “His kind demeanor makes him an ideal like-minded partner for an endeavor like this.”

For his part, Mostaghim has enjoyed introducing Garcia to the company and thinks he’s well-positioned to make valuable contributions. And, he says, “I can always count on Elvis to speak his mind. It’s a quality I admire and find very refreshing.”

Elvis Garcia, MPH ’16, DrPH ’19 (left) and Sana Mostaghim, DrPH ’18

Garcia wants Takeda to envision the vaccine’s recipients—and the logistical challenges of vaccine delivery—from the beginning. For example, are clinical trials designed so that the vaccine can be used by a broad spectrum of the population? Can the vaccine ultimately be improved to not require refrigeration, or so that multiple doses can fit in a single vial, making it more convenient for countries conducting large vaccination campaigns?

“We should think about these things during the conceptualization phase, in year zero—not year 10, when we are about to release the vaccine,” Garcia says.

Pushing for change

Neither man expected to wind up working on vaccines at a pharmaceutical company. Mostaghim’s background in global health was with charitable foundations and focused mostly on the treatment side. At the Clinton Health Access Initiative, he designed and led the organization’s global program to increase access to tuberculosis medications. Working closely with officials from ministries of health and global health agencies, he got a crash course in the politics of global health. He quickly learned that it didn’t matter how technically strong a plan might be if it didn’t work for the local health offices doing the job.

He and Garcia both decided to pursue their DELTA Projects at Takeda after hearing Rajeev Venkayya, president of the company’s global Vaccine Business Unit, speak about promoting vaccines as a public health endeavor—and both see in the company’s vaccine pipeline evidence that this is more than a talking point. In addition to dengue, Takeda is advancing programs to tackle other challenging infectious diseases including polio and Zika virus.

Mostaghim says, “They are objectively going after large, unmet needs in the world. It’s not niche products targeting high-income countries first, with the rest of the world as an afterthought.”

Given that Takeda’s global Vaccine Business Unit is relatively new, it operates like a startup in some ways. Working on the dengue vaccine candidate has given Mostaghim the chance to contribute to the template for the company’s vaccine rollouts. That includes analyzing the disease burden in each target country and its capacity to implement potential dengue vaccination programs. He’s also digging into the ways that a vaccine can affect a country’s economy and the health of its people, asking how much it will cost countries to launch a vaccine program given their existing health care infrastructure, and how much they might save in future treatment costs.

Mostaghim’s and Garcia’s understanding of the public health environment and their commitment to equity have been good for Takeda, according to Gary Dubin, senior vice president and head of the Vaccine Business Unit’s Global Medical Office. “While we are a vaccine manufacturer, what we really do is try to fulfill a public health mission—introduce vaccines in a way that will have the greatest benefit for populations in need,” Dubin says. Mostaghim and Garcia, he adds, are pushing the company to keep doing better.

Although his DELTA Project at Takeda is short term, Garcia hopes that he’ll have helped lay the groundwork for a cultural shift in the way the company—and perhaps pharmaceutical companies more broadly—think about vaccines.

A safe and effective dengue vaccine will not only save lives, but it will also lead to a healthier, more productive society, Garcia says. “It will mean adults are not getting sick, so they can stay at work and earn more money. It will mean children are not getting sick, so they can stay in school and broaden their horizons.”

As the climate continues to change in the coming decades, warmer, wetter weather is expected to expand the Aedes aegypti mosquito’s range and put millions more at risk of dengue. But a vaccine could stop the disease before it spreads. Put simply, says Garcia, “A dengue vaccine can shape the future.”

Devils, dandies, and broken bones

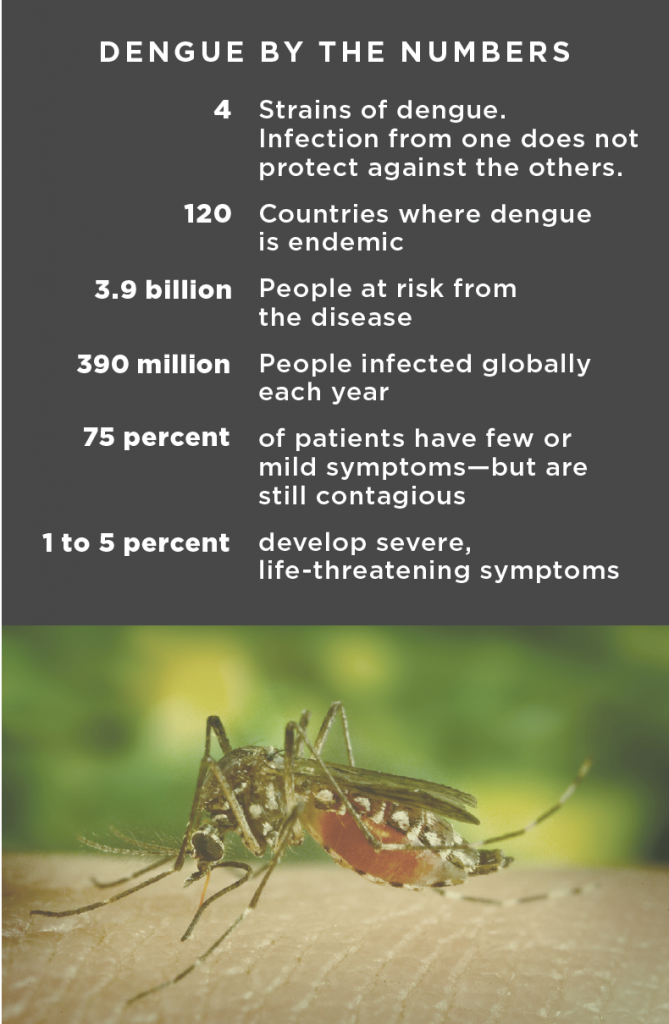

In East Africa, the disease was called kidinga pepo, translated by a 19th-century researcher from Scotland as “a cramp-like seizure caused by an evil spirit.” In the West Indies, it was “dandy fever,” for the delicate gait observed in people suffering from its characteristic muscle and joint pain. By the time it reached Philadelphia in 1780, it had picked up the name “breakbone fever.” There, a patient of physician Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, noted that it could also be called “break heart fever” for the fatigue and depression that can linger after other symptoms subside. It traveled the world in the blood of soldiers, sailors, and slaves, and in mosquitoes that bred in pools of water collected on goods in cargo ships. Now known as dengue, it is endemic in more than 120 countries, putting 3.9 billion people—about half the world’s population—at risk.

The dengue virus is transmitted by female mosquitoes, mainly of the species Aedes aegypti, which also transmits the Zika and chikungunya viruses. Out of the 390 million people infected with dengue across the globe each year, about 75 percent have no or only mild flu-like symptoms—but can still spread the disease to others.

Those with symptoms typically start to feel sick within four to 10 days of infection, and can suffer from sudden high fevers, severe pain behind the eyes, and vomiting. There is no cure, but most people get better within two weeks if they manage their symptoms with rest, fluids, and pain relievers, although fatigue can linger.

For 1 to 5 percent of patients, however, the disease takes a frightening turn into severe dengue (also known as dengue hemorrhagic fever). Patients’ blood vessels become damaged and leaky, and sufferers bleed from their gums and under the skin. As many as 20 percent can die, but most can be saved with prompt treatment. Severe dengue remains a leading cause of hospitalization and death for children in Asia and Latin America.

Dengue has four strains: DEN 1 to 4. Infection from one strain does not protect against the others—and it can actually cause antibodies to drop, raising the risk that a subsequent infection by a different strain will develop into severe dengue.

Incidence of dengue has exploded since 1970, before which only nine countries had experienced severe epidemics. The disease has spread to new areas, including Hawaii, Japan, and Russia. Warmer global temperatures and deforestation have helped mosquitoes and the viruses they carry thrive. More ominously, dengue’s second vector, the Aedes albopictus mosquito, easily adapts to new environments and can survive temperature variations—making it an ideal passenger to travel the globe in international cargo ships and spread disease.

The dengue vaccine Dengvaxia was released by Sanofi Pasteur in 2016, but there are concerns that it can put those who have not previously been exposed to the virus at risk of a more severe form of the disease. Takeda’s TAK-003 vaccine candidate passed a significant stage in its efficacy trials, the company announced in early 2019. Additional safety and efficacy data are expected later this year.

Amy Roeder is associate editor of Harvard Public Health.

Photos: AP/Manish Swarup, Cole Hanna