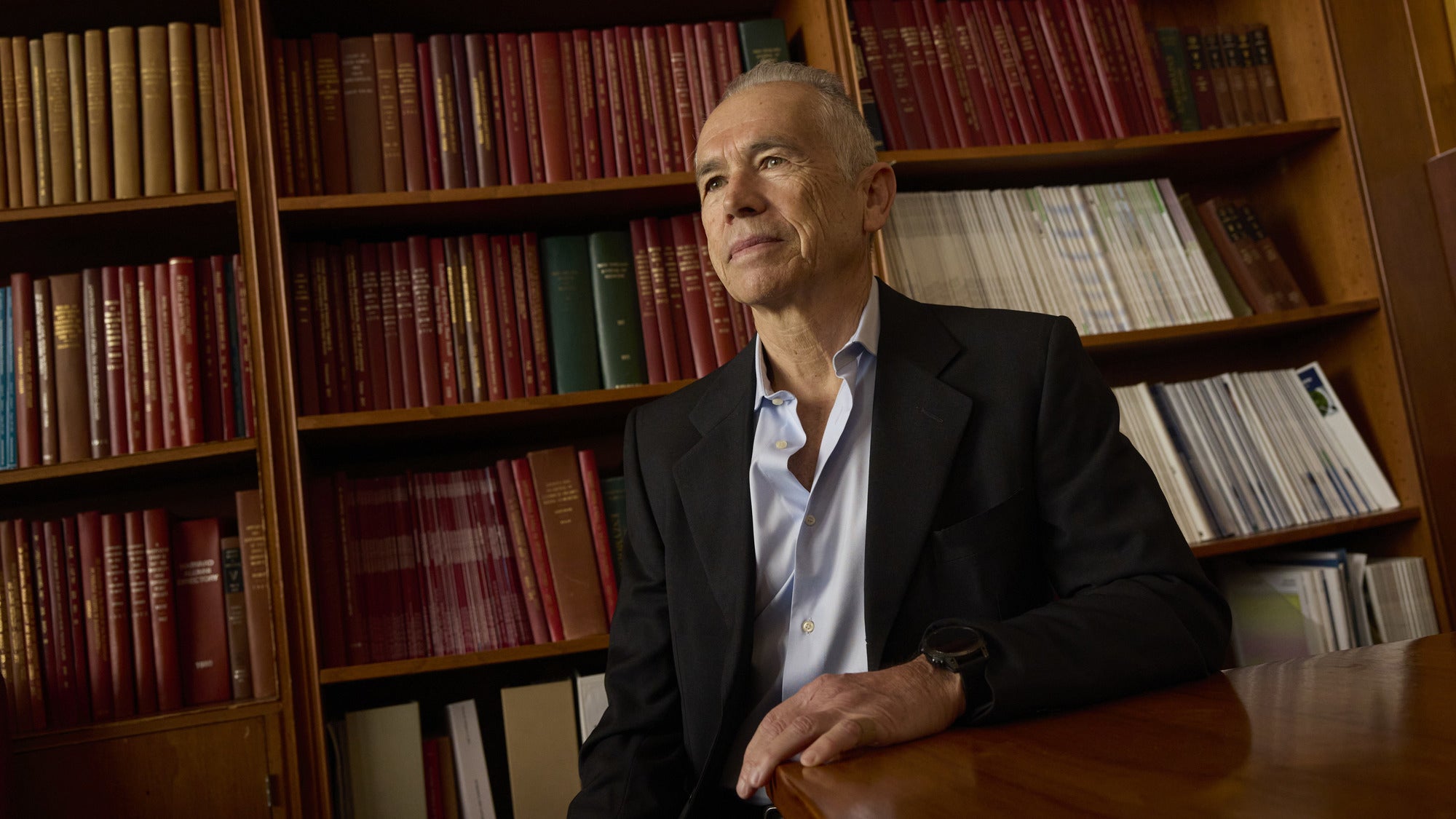

Alberto Ascherio receives Breakthrough Prize for groundbreaking research on multiple sclerosis

Award recognizes work establishing Epstein-Barr virus infection as leading cause of MS

Although there was no single eureka moment in Alberto Ascherio’s more than 25-year effort to identify the cause of multiple sclerosis, the results of his 2022 Science study were undoubtedly dramatic. Using data from more than 10 million U.S. soldiers monitored over a 20-year period, Ascherio and his colleagues found that infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) significantly increased the risk of developing multiple sclerosis (MS) later in life—the first compelling evidence of a cause for this devastating disease.

This achievement was recognized at the 11th annual Breakthrough Prize ceremony, held April 5 at Barker Hangar in Santa Monica, California. The Breakthrough Prizes were founded by Sergey Brin, Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg, Julia and Yuri Milner, and Anne Wojcicki to recognize the world’s top scientists. The ceremony will be available to stream on April 12.

Ascherio, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, shared the 2025 Prize in Life Sciences with Steven Hauser of the University of California, San Francisco, who established the role of B cells in MS and developed B-cell based treatments.

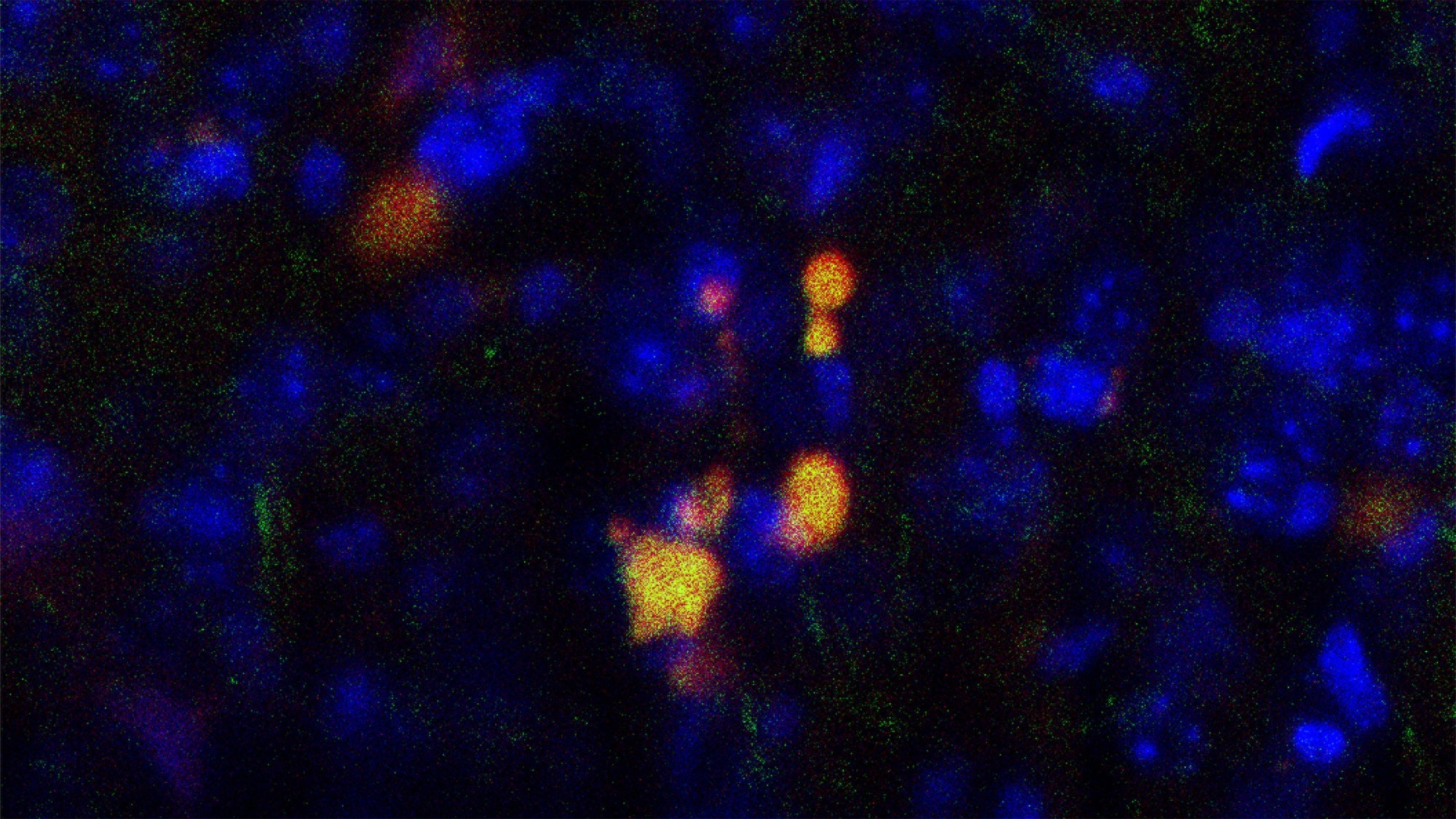

MS is a chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system that affects about 2.9 million people worldwide and currently has no cure. EBV is a herpes virus that can cause mononucleosis and establishes a lifelong latent infection.

A revolutionary study

The hypothesis that MS is caused by a viral infection has been around for more than a century, Ascherio said, although he noted that a number of poorly conducted studies had left some researchers skeptical. Ascherio found the evidence for EBV as the cause of MS to be compelling—for example, people who have had mono have a two- to three-fold increased risk—and he co-authored his first systematic review on the topic in 2000. But in order to prove causality, he and his colleagues needed what is called an “experiment of nature,” an observational study of MS incidence in a group of EBV-negative individuals, some of whom would become infected with EBV over time.

This was challenging because EBV infects approximately 95% of adults, MS is a relatively rare disease, and the onset of MS symptoms begins about 10 years after EBV infection. Then, his team was granted access to a source of data that changed everything.

Active-duty members of the U.S. military are screened for HIV at the start of their service and then screened biennially, and their blood samples are stored in the Department of Defense Serum Repository. Over the course of a 20-year collaboration with the U.S. military starting in 2000, Ascherio and his colleagues were able to analyze health data from a racially diverse population of more than 10 million individuals who served between 1993 and 2013. Using electronic databases and medical records, the researchers identified 955 soldiers who were diagnosed with MS during their period of service.

They then analyzed serum samples collected from these individuals, in addition to controls (soldiers who didn’t have MS), to assess EBV infection status. At the start of their service, 35 MS cases and 107 controls were EBV-negative. An analysis of samples from these individuals found that the risk of MS increased 32-fold after infection with EBV but was unchanged after infection with other viruses. These findings cannot be explained by any known risk factor for MS, according to the researchers, suggesting EBV as the leading cause of MS.

The discovery revolutionized the field of MS research, and a vaccine and antibody drugs that target EBV are now in development. “It’s virtually a consensus now that EBV is the leading cause of MS,” Ascherio said. “I’m happy to say that finally, after 25 years, it’s been a big splash.”

Drawn to discovery

Ascherio, who grew up in Milan, Italy, earned a medical degree from the University of Milan in 1978 and spent several years practicing medicine and public health in Central America and Africa. While he found helping his patients rewarding, he became intrigued by the possibilities for discovery offered by research.

“You realize that if you don’t prevent diseases and you don’t address the causes of disease, then people will keep getting sick,” he said. “So, I thought, can we go more to the root—to find the cause of the disease and intervene there?”

Ascherio decided to come to Harvard, where he earned an MPH in 1989 and PhD in 1992, and soon after joined the faculty. His early research focused on finding links between diet and cardiovascular disease risk, and he and other Harvard Chan School researchers notably helped demonstrate the effects of consuming different types of fats on heart disease and stroke.

Since then, his work has shifted to identifying biomarkers and modifiable risk factors for MS and other neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). There is still so much to discover about how the brain works, he said, adding with a smile, “With due respect to cardiologists, nephrologists, and gastroenterologists, I think the brain is much, much more interesting.”

He and his colleagues are continuing to investigate the mechanisms underlying the link between MS and EBV so that they can understand which infected individuals will go on to develop the disease. Their work so far has found that vitamin D deficiency, smoking, and having obesity as a child may increase risk.

They are also looking at the role viral infections may play in the development of Parkinson’s and ALS and hope to also do so for Alzheimer’s disease if they can get the funding they need.

“I think this is the time in which we could make a breakthrough on Alzheimer’s,” he said. “We have accumulated the data and the biological samples that are needed to answer very key questions on the cause of the disease.” But until he can get funding, he said, “It’s like having the Webb Space Telescope and not being able to launch it.”

Ascherio remains optimistic that progress will be made on these diseases. That’s a trait that has helped keep him going on work with such a long time horizon. “You really need to believe in what you’re doing, to have a vision,” he said. He also stressed the importance of having good collaborators and noted the morale boost achieved from regularly producing incremental results.

While Ascherio has been pleased by the attention that his MS breakthrough received, the best part, he said, is that it has attracted attention and excitement to the field—bringing the world closer to prevention or even a cure.

Learn more

Three Boston-area researchers win Breakthrough Prizes, the ‘Oscars of Science’ (Boston Globe)

$3 million Breakthrough Prize goes to scientists behind groundbreaking MS research (Live Science)

2025 Breakthrough Prize Recognizes Trailblazers in Multiple Sclerosis Research (The Scientist)