Medicaid Cuts Likely to Affect Urban Safety-Net Hospitals

The HQO Lab team collaborated with the New York Times The Upshot to understand which hospitals will be most at risk for the Medicaid cuts. This data blog was published in parallel with The New York Times story “When the G.O.P Medicaid Cuts Arrive, These Hospitals Will be Hit Hardest.”

Written by Samuel Enumah, Jessica Phelan, Jose Figueroa*, E. John Orav, and Thomas Tsai*.

* Faculty at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; Principal Investigators of the Healthcare Quality and Outcomes Lab

Medicaid Cuts and the Financial Viability of Urban, Safety-Net Hospitals

Introduction

Public Law 119-21, known colloquially as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), signed into law on July 4, 2025, will usher in significant reductions in federal spending on Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace, and Medicare, each of which will have a profound impact on access to acute care hospitals. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimates that the OBBBA will reduce federal spending on Medicaid by over $900 billion over the next 10 years. The implementation of work requirements and more burdensome enrollment verification for Medicaid and the ACA Marketplace will result in significant disenrollment from health insurance, eliminating coverage for as many as 10 million individuals from Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and the ACA Marketplace.

The OBBBA further limits the ability of states to fund the state share of Medicaid through provider taxes, which have been used by states to generate Medicaid revenue as well as federal matching funds. The moratorium on new Medicaid provider taxes and the phase-down of existing provider taxes in Medicaid-expansion states will create large funding gaps for state Medicaid programs. The net effect of these OBBBA provisions will be more uninsured individuals, leading to a growing burden of uncompensated care provided by U.S. hospitals.

Efforts by Congress to mitigate the effects of OBBBA’s Medicaid cuts have largely focused on supporting access to rural hospitals. Already facing significant financial challenges, over 150 rural hospitals have closed or converted into non-acute care hospitals since 2010. Uncompensated care in non-Medicaid expansion states following the ACA was associated with an increase in the financial vulnerability for rural hospitals. Recognizing the burden of declining Medicaid provider fees and uncompensated care to hospitals, Congress included a $50 billion Rural Health Transformation Program in the OBBBA to provide funding to states to bolster rural hospitals and rural healthcare providers. Although touted as supporting rural healthcare, the Rural Health Transformation Program faces significant shortcomings and is not expected to replace the role of health insurance in the financial viability of US hospitals.

Despite federal lawmakers’ focus on rural hospitals, the OBBBA cuts may have an even more direct impact on urban, safety-net hospitals. While rural hospital closures have drawn national attention, the closure of urban hospitals has also emerged as a cause of concern for federal regulators. With 80% of the US population residing in urban areas, the closure of urban hospitals may have an equally or even more profound population-level impact than the closure of rural hospitals. This is particularly true for safety-net hospitals in Medicaid expansion states, where Medicaid patients represent 24% of patient revenues. Additionally, nearly 1 in 4 hospitals are already characterized as financially distressed, operating with razor-thin margins and at risk for bankruptcy. Hospitals with a high share of revenue from Medicaid patients are at higher risk for financial distress than those with a low proportion of revenue from Medicaid. Further reductions in Medicaid reimbursement and the growing burden of providing uncompensated care to the uninsured may tip financially distressed hospitals further toward closure, bankruptcy, or conversion to non-hospital facilities.

Data on the key characteristics of hospitals most likely to be jeopardized by the OBBBA cuts would therefore help both federal and state policymakers preserve access to vital hospital-based care for patients. Given the multiple threats to hospitals, we examined the characteristics of hospitals with safety-net status, existing financial distress, and high Medicaid share as most vulnerable to the OBBBA cuts.

Approach

To assess the different dimensions of the OBBBA on hospital financial vulnerability, we combined data between 2021 and 2023 from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey, Medicare Healthcare Cost Report Information System, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Compendium, and the Private Equity Stakeholder Project. We categorized hospitals based on three separate criteria. Safety-net hospitals were defined as hospitals within the top quartile of Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) patient percentage. The DSH measures a hospital’s share of low-income and Medicaid patients. In addition, we created indicators for hospitals that met multiple criteria. We also examined critical access hospitals, which are small rural hospitals that provide essential healthcare services to underserved communities. Based on prior literature, we defined hospitals as financially distressed if having a modified Altman Z-score less than 1.8. The modified Altman Z-score combines measures of hospital liquidity, profitability, financial efficiency, and solvency to categorize hospitals as distressed and at high risk for bankruptcy. High Medicaid payer mix was defined as a hospital with greater than 25% admissions from Medicaid. We defined urban and rural status of hospitals by the United States Department of Agriculture Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes, which are more granular than county-level definitions. Additionally, we reported a measure of Medicaid market competition based on the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) calculated by hospital market share of Medicaid admissions in a hospital referral region.

We then identified a group of hospitals that may represent an apex of vulnerability to OBBBA-related cuts with a combination of safety-net or critical access hospital status, financial distress, and high Medicaid payer mix.

Findings

Our sample included 4,412 general acute care hospitals, of which 2,032 (46.1%) were either SNH or CAH; 424 (9.6%) were SNH/CAH and financially distressed; and 109 (2.5%) were SNH/CAH, financially distressed, and with a high Medicaid share.

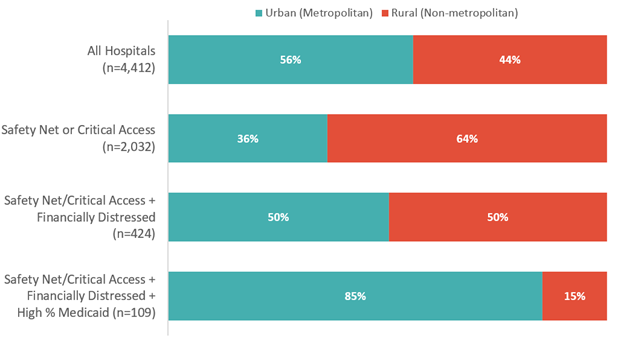

With each component of vulnerability from the OBBBA Medicaid cuts, there was an increasing proportion of hospitals that were in urban areas (Exhibit 1). Across the overall sample, 56% of hospitals were considered urban. Because critical access hospitals are in rural communities, the sample of safety-net or critical access hospitals was 36% urban. However, the urban proportion of safety-net or critical access hospitals that also had financial distress as measured by the modified Altman Z-score was 50%. When factoring the hospitals with high proportions of Medicaid patients, 85% of hospitals most vulnerable to OBBBA Medicaid cuts were located in urban areas.

Exhibit 1: Proportion of Urban and Rural Hospitals Among Measures of Hospital Vulnerability to OBBBA Medicaid Cuts

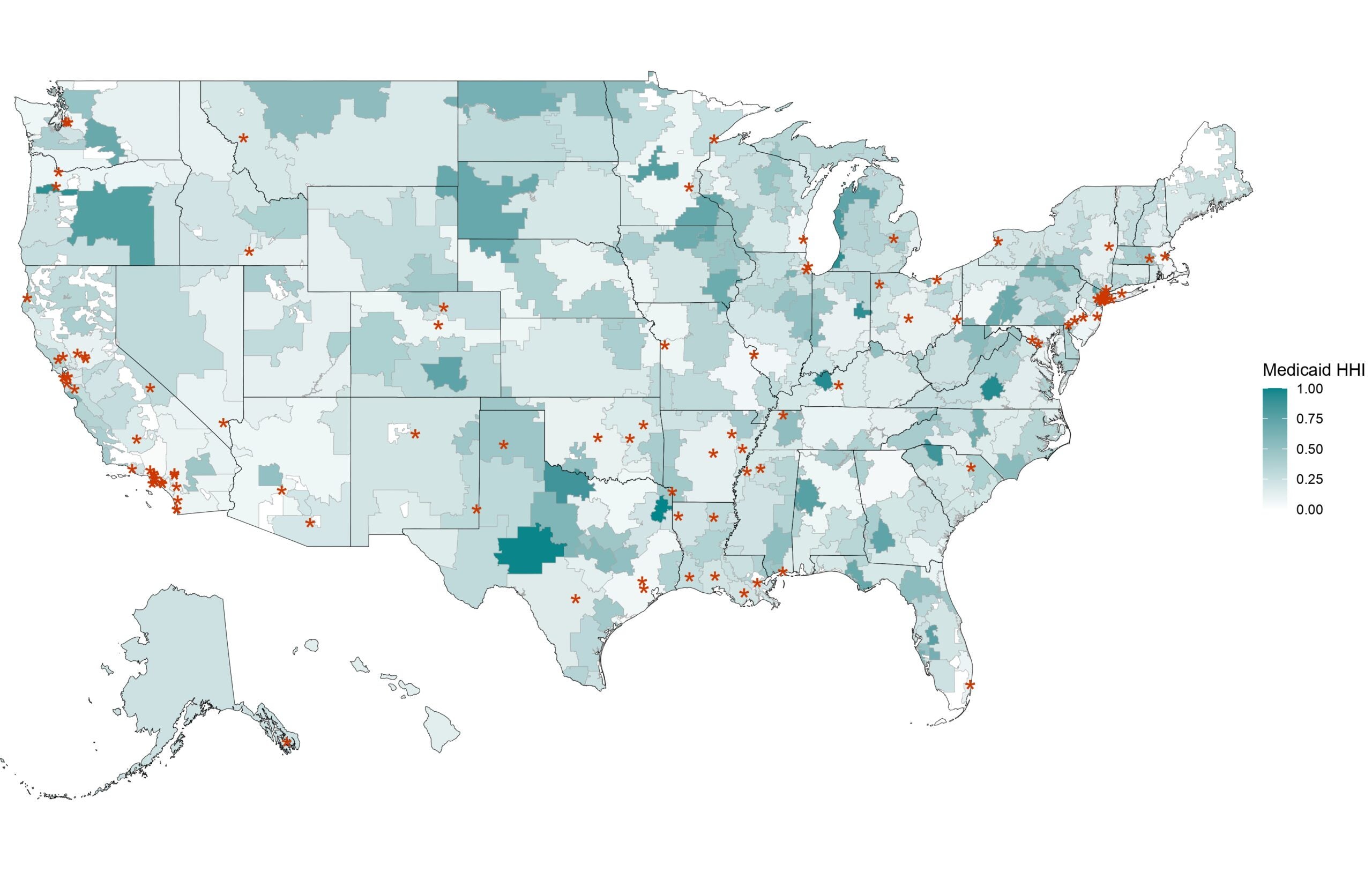

Of the 109 hospitals that met the criteria of being SNH/CAH status, financially distressed, and possessing high Medicaid payer mix, they were more likely to be in areas where the Medicaid market was less concentrated (Exhibit 2). 39.4% of these hospitals were major teaching hospitals and 92.7% were members of a health system. These hospitals were more concentrated in the Northeast (22.9%) and West (41.3%). Whereas 4.9% of the overall hospital sample were private-equity-owned, 7.3% of these hospitals were owned by private-equity. Critical access hospitals represented 4.6% of this group of highly vulnerable hospitals.

Exhibit 2: Map of HRR-level Medicaid Herfindahl-Hirschman Index and Hospitals Meeting Three Indicators of Hospital Vulnerability to OBBBA Medicaid Cuts

Policy Implications

Our analysis suggests that urban hospitals represent an underappreciated group that may be particularly vulnerable to OBBBA-related challenges, due to the combination of safety-net status, existing financial distress, and high Medicaid payer mix.

Interestingly, rural critical access hospitals are not highly represented in this final group of hospitals most vulnerable to OBBBA Medicaid cuts. Prior research has suggested that in rural settings, non-profit critical access hospitals may be more profitable than non-profit non-critical access hospitals. Federal policy, such as cost-base reimbursement of 101% of reasonable costs by Medicare to critical access hospitals, may buffer some of the impact of OBBBA-related Medicaid cuts. Beyond rural hospitals, policymakers should closely monitor the health and performance of safety-net hospitals facing challenging financial and operating conditions, especially if accompanied by a high Medicaid patient mix in highly competitive markets. Preserving access to hospital care for patients served by these hospitals should be a federal and state policy priority.

The heterogenous mix of rural and urban safety-net hospitals with financial vulnerability raises important policy considerations. The anticipated burden of uncompensated care will present additional financial strain to an already struggling healthcare delivery system. After the implementation of Medicaid coverage expansion as part of the ACA, U.S. hospitals in expansion states saw a decline in uncompensated care and an increase in organizational profitability. The OBBBA is expected to reverse these ACA-era gains, and these hospitals may encounter a return to higher uncompensated care costs. The increased financial stress on hospitals may further accelerate the trend towards hospital closure or acquisition of hospitals by private equity funds. Acquisition of hospitals by private equity funds has been associated with increased adverse events, worse patient experience, increased surgical mortality, and further financial distress as they are sold and re-sold. Policymakers should monitor the consequences of the OBBBA on hospital quality of care and outcomes.

Second, the $50 billion Rural Health Transformation Program is inadequate in both size and scope to the looming threat to hospital access for vulnerable patient populations. The $50 billion fund is estimated to make up less than 40% of the estimated loss of federal Medicaid funding. The Rural Health Transformation Program distributes $25 billion equally among states with approved applications despite the varying rural population and number of rural hospitals across states. An equal distribution across all states regardless of their degree of need will create unequal downstream effects in terms of rural hospital financial performance and rural patient access. Additional funding with greater flexibility and improved regulation will create more optimal conditions for rural hospitals. Transparency has been lacking regarding CMS priorities for the discretionary aspects of the fund. With many urban, safety-net hospitals predicted to be most at risk from the OBBBA, the failure to include these facilities and children’s hospitals is a glaring oversight by federal lawmakers.

Finally, mechanisms to directly support safety-net hospitals are needed. The Medicaid DSH program supports hospitals that provide care for children, veterans, Medicaid patients, and uninsured individuals. Many hospitals have historically relied on DSH payments and state directed payments to offset the underpayment for care of these vulnerable populations. The ACA reduced Medicaid DSH payments as Congress expected hospitals would provide less uncompensated care with the expansion of Medicaid and the ACA Marketplace. The implementation of these cuts was delayed for multiple years, but the DSH payment reductions went into effect in October 2025. The initial House version of the reconciliation bill had proposed delaying the start of DSH payment reductions, but this compromise was removed from the Senate and enacted version of the OBBBA. In addition to the financial vulnerability created with DSH payment cuts, the OBBBA cuts may increase the amount of uncompensated care provided by both rural and urban safety net hospitals. As hospitals encounter the continued challenges of reduced reimbursement and rising expenses, hospitals and health systems may be pushed to eliminate clinical services or convert to emergency rooms or outpatient facilities. Policymakers should explore opportunities to bolster financial support for hospitals that would be most affected.

Hospitals caring for vulnerable populations are at a critical juncture. Many hospitals lack the appropriate resources that they need to deliver necessary care to millions of people across the country with the return to high rates of uninsured individuals and uncompensated care provided by hospitals. With the future of healthcare at stake, hospitals caring for our most vulnerable patients need more, not less, federal and state support.

For more information, contact Thomas Tsai at ttsai@hsph.harvard.edu

The Healthcare Quality and Outcomes Lab (HQO) is a state-of-the-art health services research group that produces actionable evidence to improve the quality, equity, and resilience of healthcare delivery systems.