Apple Women’s Health Study

The Apple Women’s Health Study is the first long-term research study of this scale and scope that aims to advance the understanding of menstrual cycles and their relationship to various health conditions.

Connecting the dots between irregular periods, polycystic ovary syndrome, and endometrial cancer risk

Researchers are studying the relationship between polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and time to cycle irregularity with endometrial cancer and hyperplasia in the Apple Women’s Health Study.

AUGUST 2023: You are not alone if your menstrual cycle does not come each month like clockwork. As many as one in four people who menstruate have menstrual irregularities1,2. There are many different types of menstrual irregularities and causes for those changes.

Your menstrual cycle could be irregular if your cycles are unpredictably short (fewer than 21 days apart), long (more than 35 days apart), or spaced out (going longer than three months in between periods). Potential causes of these changes can be pregnancy, using hormonal birth control, stress, illness, endometriosis, sexually-transmitted infections, and hormone disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)1,2.

With the help of participants in the Apple Women’s Health Study (AWHS), we are working to better understand the relationship between changes in menstrual cycles, PCOS, endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial cancer.

Why look at PCOS and menstrual irregularities?

As many as 1 or 2 people who menstruate out of every 10 may have PCOS in the U.S3,4. PCOS induces a hormone imbalance leading to metabolic and fertility problems. Those with PCOS commonly miss periods or have fewer than 8 periods in a year.4 Study update #4, which focused on periods, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and heart health, reviewed some preliminary findings from AWHS, showing that participants with PCOS are more likely to have obesity and pre-diabetes than those without PCOS.

The relationship between PCOS, menstrual irregularities, body size, and endometrial cancer risk is complex. Some conditions which cause less frequent menstruation and menstrual irregularities can result in the thickening of the lining of the uterus (endometrial hyperplasia)5. Endometrial hyperplasia, if not treated, can possibly progress to cancer of the lining of the uterus, called endometrial cancer. People who do not have PCOS, but have higher BMIs, may still be at risk for endometrial hyperplasia and cancer especially if they also have irregular periods.

Researchers and healthcare providers want to find better ways to identify people at high risk for endometrial hyperplasia and cancer.

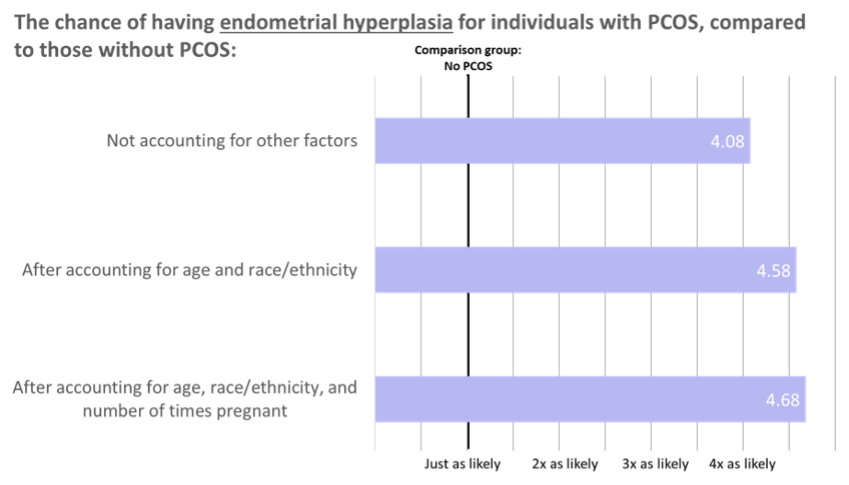

The Apple Women’s Health Study provides valuable insights that may help patients with irregular cycles or PCOS who are at increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. Preliminary analysis shows that:

- People with PCOS were more likely to have had endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer compared to people without PCOS.

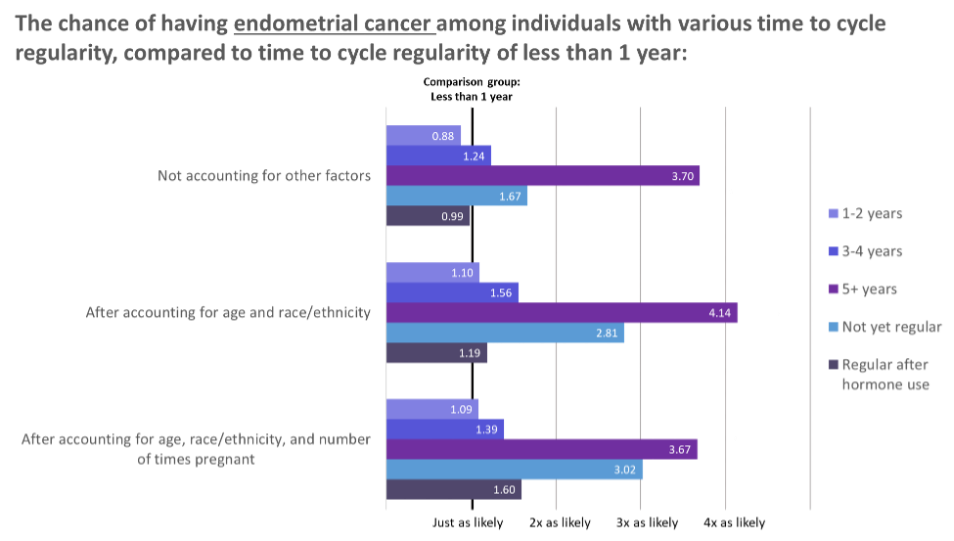

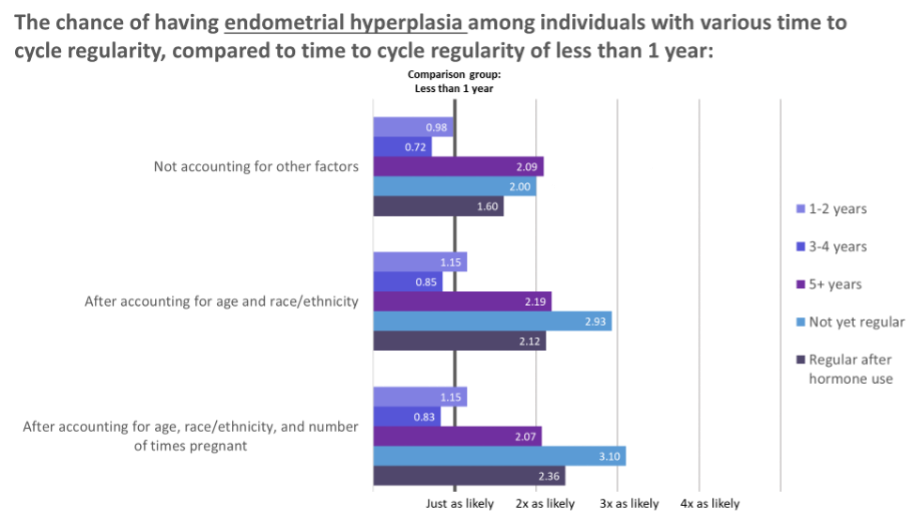

- People who had irregular cycles for a longer period of time (5 or more years) before establishing regular cycles were more likely to have been diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial cancer compared to people who had established regular cycles within one year of having their first period.

What questions about menstrual cycle regularity and endometrial cancer risk did the AWHS ask?

For this part of the study, the AWHS collected data from people with periods across the United States, starting in November 2019 and running through August 2022. Researchers asked 54,363 participants questions about:

- Whether they had ever been diagnosed with PCOS.

- How many years after starting to menstruate did they have regular cycles (Less than 1 year, 1-2 years, 2-3 years, 3-4 years, 4-5 years, 5+ years, not regular yet, or only regular after using hormones).

- Whether they had ever been diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial cancer at the time of study enrollment.

Study participants answered additional health-related questions about age, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), family health conditions, number of pregnancies, and physical activity level. These factors can influence how regular cycles are and the risk for endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer.

Who participated in this part of the AWHS?

Most of the participants in this study were within their reproductive years (median age 33, range 18 to 90), white (70 percent), had been pregnant two or more times (38 percent), and were overweight or obese by self-reported BMI (60 percent).

Twelve percent of the AWHS participants reported having a diagnosis of PCOS. This is consistent with the published reported rate of PCOS of 10-20 percent worldwide3. Seven percent of the AWHS participants reported having a family history of PCOS. Those with PCOS were more likely to report a family history of PCOS, which aligns with prior research suggesting that PCOS can run in families and be inherited6.

One out of every three study respondents (33%) achieved cycle regularity in less than one year, but 5 percent (one out of 20 study respondents) took at least 5 years to have regular cycles. Another 10 percent (or one out of every 10 study respondents) reported achieving regular cycles only after using hormones.

How are PCOS, endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial cancer related?

When not balanced with another naturally produced hormone called progesterone, higher estrogen levels can cause the uterine lining to grow too thick (called endometrial hyperplasia).

The most common cause of excess estrogen in people with periods is having an elevated BMI due to excess fat cells because fat cells also can produce estrogen. People with PCOS are more likely to have excess estrogen and higher BMIs3,4.

The longer someone goes without shedding the lining of the uterus (or having a period), in the setting of chronic estrogen exposure, the greater their risk for endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer. There are multiple reasons why a person who menstruates might experience an irregular bleeding pattern. The connection between persistent irregular bleeding and endometrial hyperplasia is why anyone with a persistent irregular bleeding pattern, or any irregular bleeding concern, should check in with their healthcare provider.

AWHS data shows a connection between PCOS, endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial cancer.

In the AWHS, respondents reporting having PCOS also reported having endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial cancer at higher rates.

These data are based on self-reported conditions (PCOS, endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial cancer), without confirming a diagnosis from medical records, for example.

Remember that this observation made from participant data does not prove that PCOS causes endometrial hyperplasia or cancer. But it does provide evidence that having PCOS might be a risk factor for the development of endometrial hyperplasia or cancer.

Knowing about this connection for those with PCOS could help inform the decision to see a healthcare provider sooner if an individual has irregular bleeding.

Why is AWHS different from previous studies of menstrual irregularity and endometrial cancer?

So far, researchers studying connections between PCOS, cycle irregularity, and endometrial hyperplasia and cancer have looked at either European population data or the hospital records of people with endometrial cancer. Unfortunately, this limits our ability to make conclusions or treatment decisions for younger, healthier individuals or those in the U.S. with different risk factors. With the information provided by the AWHS, doctors, and researchers may be better able to care for those at the highest risk for hyperplasia or endometrial cancer.

What does time to menstrual regularity tell us?

Apple Women’s Health Study researchers were excited to find a new marker or way to track people’s risk for developing endometrial hyperplasia or cancer. They proposed using the length of time it took to establish regular cycles as an indicator of risk.

They hypothesized that people who took longer to have regular cycles might be more likely to have PCOS. They also reasoned that those people who took longer to establish longer cycles (whether or not they had PCOS) might also be more likely to have endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial cancer.

Looking at the data collected from AWHS participants, those who took 5 or more years to have regular cycles, or required hormones to regulate their cycles, (16 percent) were more likely to have a self-reported PCOS diagnosis.

Participants who took at least 5 years to have regular cycles, did not yet have regular cycles, or took hormones to regulate cycles were also more likely to report having a diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer. reached cycle regularity in less than 1 year,

Analysis of participant data helped illustrate a trend between the time to cycle regularity and endometrial cancer risk. The trend shows that the longer people take to have regular cycles, the greater their risk for endometrial cancer. The ability to demonstrate a trend response with time to menstrual cycle regularity strengthens the case for using the time to menstrual cycle regularity as a valid marker for endometrial cancer risk.

AWHS participants’ data may help us better understand and prevent endometrial cancer.

Approximately one out of every 40 individuals who menstruate will develop endometrial cancer7. Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecological cancer – more common than ovarian or cervical cancer8. The number of individuals with endometrial cancer has increased over time as rates of obesity have also increased. Prior studies have shown that irregular and prolonged menstrual cycles throughout the reproductive lifespan are associated with an increased risk for cancer, especially obesity-related cancers9.

Endometrial cancer is more common in those who no longer menstruate. The average age of someone diagnosed with endometrial cancer is 60. This cancer is more common in Black than White people who menstruate, and for Black individuals survival rates are lower8.

The early stages of endometrial cancer, called endometrial hyperplasia, are highly treatable. There are effective screening and treatment options for endometrial hyperplasia that could help save lives, especially for those identified as having the highest risk for endometrial cancer5.

With data from large numbers of diverse people with periods, doctors and scientists can identify those at the highest risk using markers such as a PCOS diagnosis or taking a long time to reach cycle regularity. The willingness of participants to share their health journey through the Apple Women’s Health Study allows us to connect the dots between PCOS, menstrual cycle irregularity, and endometrial hyperplasia.

The Apple Women’s Health Study team thanks its participants for their continued contributions to public health research.

More information on Apple Research app & Privacy

- Whitaker, L., & Critchley, H. O. D. (2016). Abnormal uterine bleeding. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 34, 54–65. Retrieved June 23, 2016, from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1521693415002266

- National Center for Child Health and Development. NIH. What are menstrual irregularities? Accessed online: April 2023.

- Azziz, R., Carmina, E., Chen, Z., Dunaif, A., Laven, J. S., Legro, R. S., Lizneva, D., Natterson-Horowtiz, B., Teede, H. J., & Yildiz, B. O. (2016). Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nature reviews. Disease primers, 2, 16057.

- Office on Women’s Health. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Accessed online: April 2023.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG). Endometrial hyperplasia. FAQ’s. Accessed online: April 2023.

- National Cancer Institute. Epidemiology of Endometrial Cancer Consortium (E2C2). Accessed online: April 2023.

- Uterine cancer statistics. Accessed online: April 2023.

- American Cancer Society. Key facts about endometrial cancer. Accessed online: April 2023.

- Wang S, Wang YX, Sandoval-Insausti H, et al. Menstrual cycle characteristics and incident cancer: a prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2022;37(2):341-351.