‘I’m going to fix everyone’

Despite his challenging start in rural Jamaica, James Frater, MPH ’24, overcame enormous obstacles to achieve his lifelong goal of becoming a doctor. Along the way, he’s helped others dream big.

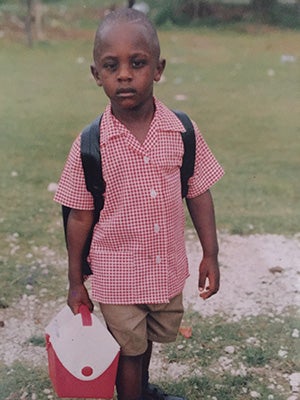

February 14, 2024 – Even at a young age, James Frater knew it wasn’t normal to get rushed to a hospital every few weeks to be treated for his uncontrolled asthma. Growing up in Portland, Jamaica—an area with few medical resources—meant that the condition was potentially deadly for him.

“A couple of times, it was nearly life-ending,” said Frater. “I recognize now that I wouldn’t have survived without a car that could take me to the hospital in the middle of the night, or the money to buy the medication and equipment we needed at home to keep me alive.”

Frater’s distressing experiences led to his declaration at age five that he was going to become a doctor. He had grand ambitions to set up a backyard clinic, so he started “treating” his first patient, his late grandmother, for endless imaginary illnesses. “I was like, ‘I’m going to fix everyone.’”

Following through on that commitment wasn’t always easy—Frater faced financial obstacles and long-undiagnosed dyslexia—but he made good on it, earning a medical degree from London’s King’s College in 2022. Pure stubbornness kept him going. “Becoming a doctor was the only thing I ever wanted to do,” he said.

Along the way, however, he realized that while a doctor could treat one person at a time, “fixing everyone” would require a more systemic understanding of health inequities. That’s what led him to Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, where he’s pursuing a master of public health degree with a health management concentration. His aim is to transform health systems in underserved communities like the one he grew up in, both by improving health care quality and access to care.

Making dreams reality

Spurred partly by the need to find better treatment for Frater’s asthma, his family moved to London in 2002 when Frater was six. But the family—like other Caribbeans living in the U.K.—faced the challenge of longstanding discrimination. “In the U.K., Caribbean communities have been systematically excluded from education and jobs they have been qualified for,” Frater explained.

While Frater did well in school and his family was incredibly supportive of his ambitions, they lacked the financial or social capital to make his dreams of becoming a doctor a reality. “I didn’t know anyone who had gone to medical school in my immediate network,” he said.

Looking back

“I don’t think I could have prepared myself for the amount of opportunities I was going to get whilst at Harvard.”

We asked James Frater, MPH ’24, to reflect on a video of himself at Harvard Chan School’s orientation when he first started. Now, on the eve of his graduation, he’s realizing the importance of the connections he’s made at Harvard Chan School.

Frater was fortunate to find mentors throughout his journey to help him succeed. For example, his secondary school English teacher went above and beyond to tutor him at 7:30 a.m., several days a week, enabling him to meet the requirements to apply for competitive medical degree programs. In addition, The Amos Bursary, a charity that supports talented young British students of African and Caribbean heritage, was instrumental in providing the personal, professional, and academic development that eventually led to his acceptance at King’s College London.

Before Frater started at King’s, during a gap year, The Amos Bursary and Imperial College London facilitated him spending three months in The Gambia focusing on helping others. He assisted with a research project aimed at showing that effective screening, treatment, and prevention of Hepatitis B can lower the incidence of liver cancer. He also taught math and English in local orphanages. While it was rewarding to work with the children, he said, it was also “very saddening for me because you could see that a lot of these children were very bright, and with the right resources they could excel.” The experience made him even more aware of the disparities that hold some people back from opportunities and prompted him to redouble his efforts to rectify that.

Coming to King’s in 2015, he immediately noticed the lack of other students from Caribbean backgrounds, and convinced The Amos Bursary to partner with the university to hold an annual conference that Frater hoped would encourage students to apply to the best universities in the U.K., including King’s. Over 60 students attended the conference in the first year in 2017—a number that grew to 400 by 2020—and led to the creation of two undergraduate scholarships at King’s for British males of African or Caribbean descent. In subsequent leadership roles at King’s—as an Access to Medicine Ambassador and as president of the King’s College African and Caribbean Society—Frater ran support groups for students and persuaded the university to set specific targets for African and Caribbean students from resource-poor backgrounds.

“A lot of this work has been informed by my own experience and the barriers I’ve faced,” he said. “You see so much talent out there, and the people who get access to opportunities aren’t necessarily the best students or the ones who deserve them the most.”

In the midst of earning his medical degree, he also took a year off to earn a bachelor’s degree in management at Imperial College London to expand his capacity to serve communities in need. “Studying medicine taught me how to treat people individually,” he said, “but I recognized that to create more equitable access to health care I had to learn about providing it at an organizational and systems level, which is why I pursued the management degree.” Frater also worked as an intern at several organizations, including Google Cloud, KPMG, and Aviva Health, during his years at King’s and Imperial.

Frater also found time to co-found a social enterprise called The Ladder Project to teach essential skills to students from underprivileged backgrounds. “A lot of students go through school without the skills they need to thrive—stuff like networking, public speaking, and creating a personal brand—so we wanted to fill that gap and make sure that they could stand out from their peers,” he said.

Frater has racked up a slew of awards, including some recognizing his efforts to give back to society. For example, he received a 2020 Diana Award for his work addressing racial inequalities and access to education—and for which he got a shout-out from Prince Harry during a virtual awards presentation.

In June 2022, shortly before finishing medical school, Frater took to the TEDx stage to talk about “living audaciously,” emphasizing the importance of living a life you choose and not one that has been given to you. He described his friend Sherain Watson, who even while battling cancer was determined to live life on her terms, including riding a bike after hip surgery. He told the story of another friend, Vee Kativhu, who persevered through unlikely odds to attend Oxford and Harvard and then create an academic empowerment charity to improve opportunities for young girls worldwide facing hardships. And he shared his own story, about pursuing a career in medicine even though the odds were against him. “It’s important you live a life that you choose,” he said in the talk. “And more importantly help others live a life that they choose too.”

Focusing on inequities

Over time, Frater has become more interested in the social determinants of health—such as the transportation that allowed him to get to the hospital as a child—and how they create inequities in the health system. “As a doctor, you only see the people who come to the hospital, but so many people never make it,” he said. “I wanted to help to solve those problems too.”

At Harvard Chan School, he’s been able to gain a broader perspective on the systemic inequalities that can impact health. Working with David Williams—Florence Sprague Norman and Laura Smart Norman Professor of Public Health, chair of the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, and a top expert on issues of racial inequities in medicine—Frater has done research and writing on the topic of Caribbean health inequities. For his practicum, he is working with Community Solutions, a nonprofit dedicated to ending homelessness, to create a policy playbook and implementation guide to help states and cities in the U.S. with strategies to address the issue through a public health framework.

True to form, Frater has also pushed Harvard Chan School to do more for the local Boston community. After the School ran a Day of Service in early October, he advocated to schedule a second one. “I was a little bit naggy to be honest,” he admitted. On the second Day of Service, held in December, Frater led a group of volunteers in helping pack winter kits with warm weather gear, snacks, and personal care products for people without housing, and fill backpacks with school supplies for newly arrived refugee and immigrant families.

While he isn’t sure where his path will take him next, Frater plans in the near term to continue focusing on homelessness and global health issues. He said, “I hope to leverage everything I’ve learned at the School to set myself up for a role in health organizations that are really innovating on issues of health equity, and that allows me to serve the people who need help most.”

Feature photo: Kent Dayton; Other photos courtesy James Frater