Fighting the health inequities laid bare by COVID

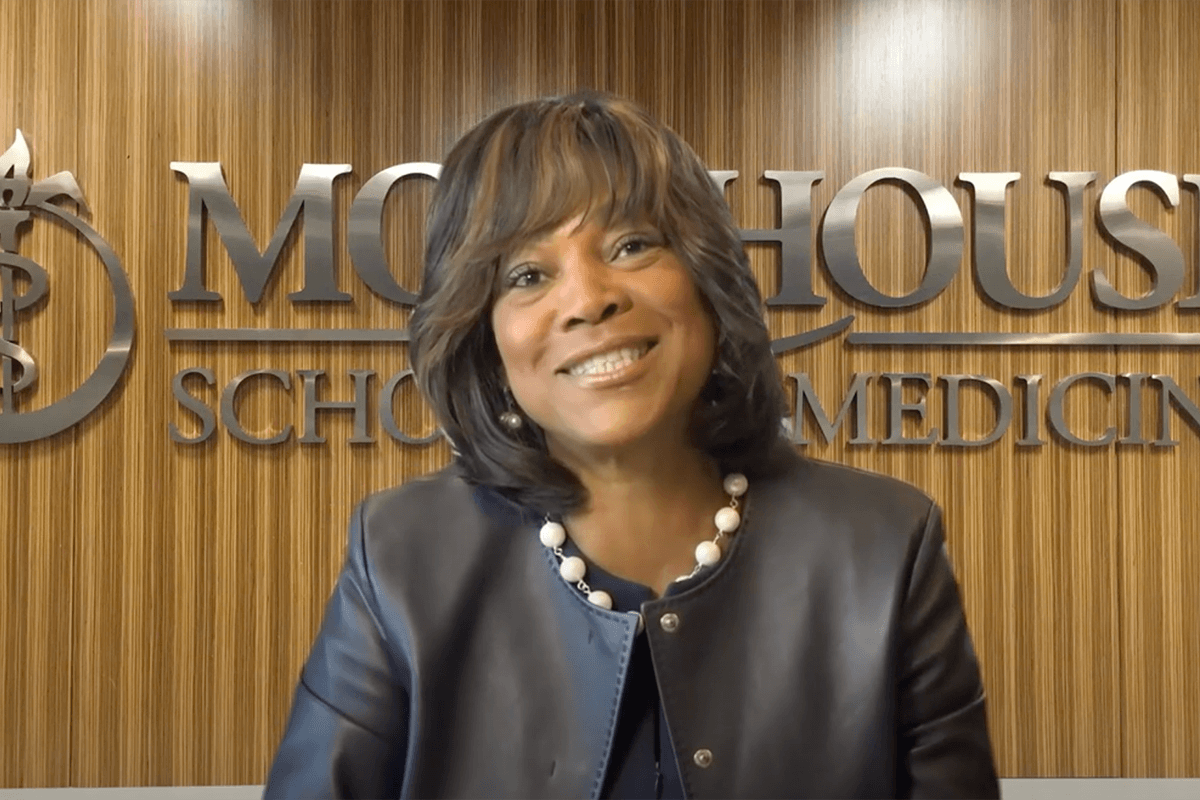

March 8, 2022 – Over the course of the coronavirus pandemic, it’s become clear that poorer people and racial minorities have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19. Morehouse School of Medicine’s (MSM) Valerie Montgomery Rice talked about her school’s efforts to fight this health inequity—and what more can be done about it—during a virtual talk at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

President and CEO of MSM, Montgomery Rice gave the Yerby Diversity Lecture in Public Health on March 2, 2022. The lecture series, which brings minority scientists and scholars to the School to speak on important health topics, honors the late Dr. Alonzo Smythe Yerby, a public health pioneer, former associate dean at Harvard Chan School, and its first Black department chair.

Starting in 2020, Montgomery Rice said, MSM researchers began investigating the impact of COVID-19 on minority communities in the context of the long legacy of slavery in the South. “We understood that the institution of slavery is the root cause of institutionalized racism in the United States,” Montgomery Rice said. “We know that the effects of slavery persist as racist policies, and that the Southeast area has the worst outcomes.”

Looking at counties across the U.S., researchers at MSM’s National Center for Primary Care sought to uncover connections between the proportion of enslaved people in 1860 and COVID case and death rates during the first six months of the pandemic. They found that every 1% increase in the proportion of enslaved persons in a particular county in 1860 was associated with a 1.6% higher COVID case rate, and a 0.8% higher COVID death rate. Other studies, too, have shown the pandemic’s outsized impact on Blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans. For example, those groups represent 60% of cases in Georgia, despite making up only about 40% of the population.

“So how did we meet this moment?” Montgomery Rice asked. First, she said, it was crucial to engage with communities, working with trusted community health workers and community-based organizations to help overcome skepticism about vaccination and other measures to stop the spread of the virus.

Through the Black Coalition Against COVID, Morehouse and other Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) worked with Black medical professionals to hold town meetings and engage in outreach to disseminate accurate scientific information to disproportionately impacted communities and increase vaccination rates. With a $40 million grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Morehouse also spearheaded the National COVID-19 Resiliency Network, a central clearinghouse where people can find up-to-date information on vaccination, testing, and other medical and social services.

“They can put their ZIP code in and find testing and vaccine locations and get a GPS link they can follow on their phone,” Montgomery Rice said. Now the Resiliency Network is expanding its services to include referrals to hospitals for routine medical care and preventive screenings delayed due to the pandemic. In addition, Montgomery Rice said, Morehouse has created a Health Equity Tracker, funded by Google and other sources, that has pulled demographic and health data from multiple sources to create a single platform to show how certain communities in the U.S. face disparate health impacts, to give policymakers accurate information when allocating resources in the future.

Finally, Montgomery Rice said, Morehouse has looked at what it can do directly as one of the nation’s four historically Black medical schools to reduce health disparities. Drawing from data showing that patients fare consistently better when treated by doctors from a similar background and experience, Morehouse recently announced an ambitious 10-year, $100 million partnership with CommonSpirit Health to recruit and train more Black physicians, including the creation of five regional medical campuses in disadvantaged areas.

Morehouse will also work to recruit more faculty of color and reduce unconscious bias and discrimination in the curriculum at medical schools. “I hope that COVID-19 will be a catalyst for us to think about population health in general, and how we need to direct resources to communities that are underserved and undervalued, so we can have access on the front end rather than having to be reactionary,” Montgomery Rice said. “There is an opportunity here to do something here that will have long-term consequences.”