Zip code better predictor of health than genetic code

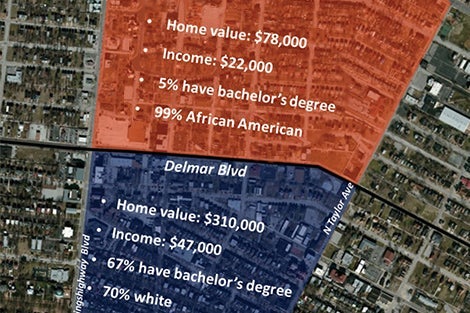

August 4, 2014 — In St. Louis, Missouri, Delmar Boulevard marks a sharp dividing line between the poor, predominately African American neighborhood to the north and a more affluent, largely white neighborhood to the south. Education and health also follow the “Delmar Divide,” with residents to the north less likely to have a bachelor’s degree and more likely to have heart disease or cancer.

Pointing to Delmar as an example, Melody Goodman, an assistant professor at Washington University in St. Louis, recently spoke to a Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) audience about the links between segregation and poor health. An HSPH alumna, Goodman gave the keynote address at the first annual symposium sponsored by the Department of Biostatistics Summer Program in Quantitative Sciences. She told the audience at the July 24, 2014 event, which was held at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, “Your zip code is a better predictor of your health than your genetic code.”

The Biostatistics summer program for undergraduates — now in its 20th year — is a model for increasing diversity at HSPH, Meredith Rosenthal, associate dean for diversity at the School, said in her introductory remarks. It aims to increase the number of students from underrepresented groups in computational biology and biostatistics graduate programs. Goodman participated in 2001, before going on to earn her PhD in biostatistics from HSPH in 2006. The symposium included research presentations from the students in this year’s class.

In her address, Goodman described her unconventional path into academia. An African American who grew up poor in New York City, she said, “If you put my demographic information into a social epidemiology model, I am more likely to be a teen mom than a Harvard grad.” She was fortunate to have people along the way who believed she had the intelligence to make something of her life, she said, even if it took her awhile to figure out her path. After earning a bachelor’s degree in applied mathematics at SUNY Stony Brook, she accepted a job on Wall Street for the paycheck, she said. Two years later, miserable, she did a web search for “math and health” and discovered biostatistics and HSPH.

Now, Goodman works to address health disparities by developing ways to quantify influential factors such as racism, white privilege, discrimination, and community engagement. “We can’t address what we don’t measure,” she said.

Goodman said that the ultimate goal of her work in health disparities is moving beyond identifying problems to finding solutions that create healthy communities for everyone.

Graphic: courtesy of For the Sake of All