Each year, millions of people are diagnosed with tuberculosis (TB) incorrectly, leaving their true health conditions unknown and untreated, according to a new study led by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The study was published Jan. 7 in Nature Medicine. Nicolas Menzies, associate professor of global health, was the corresponding author.

Missed cases of TB are a well-established global health problem, known to have serious consequences for patients and for the continued spread of the world’s top infectious disease killer. False positive diagnoses have received far less attention and study. But, Menzies explained in a Feb. 6 NPR article, their consequences can also be severe.

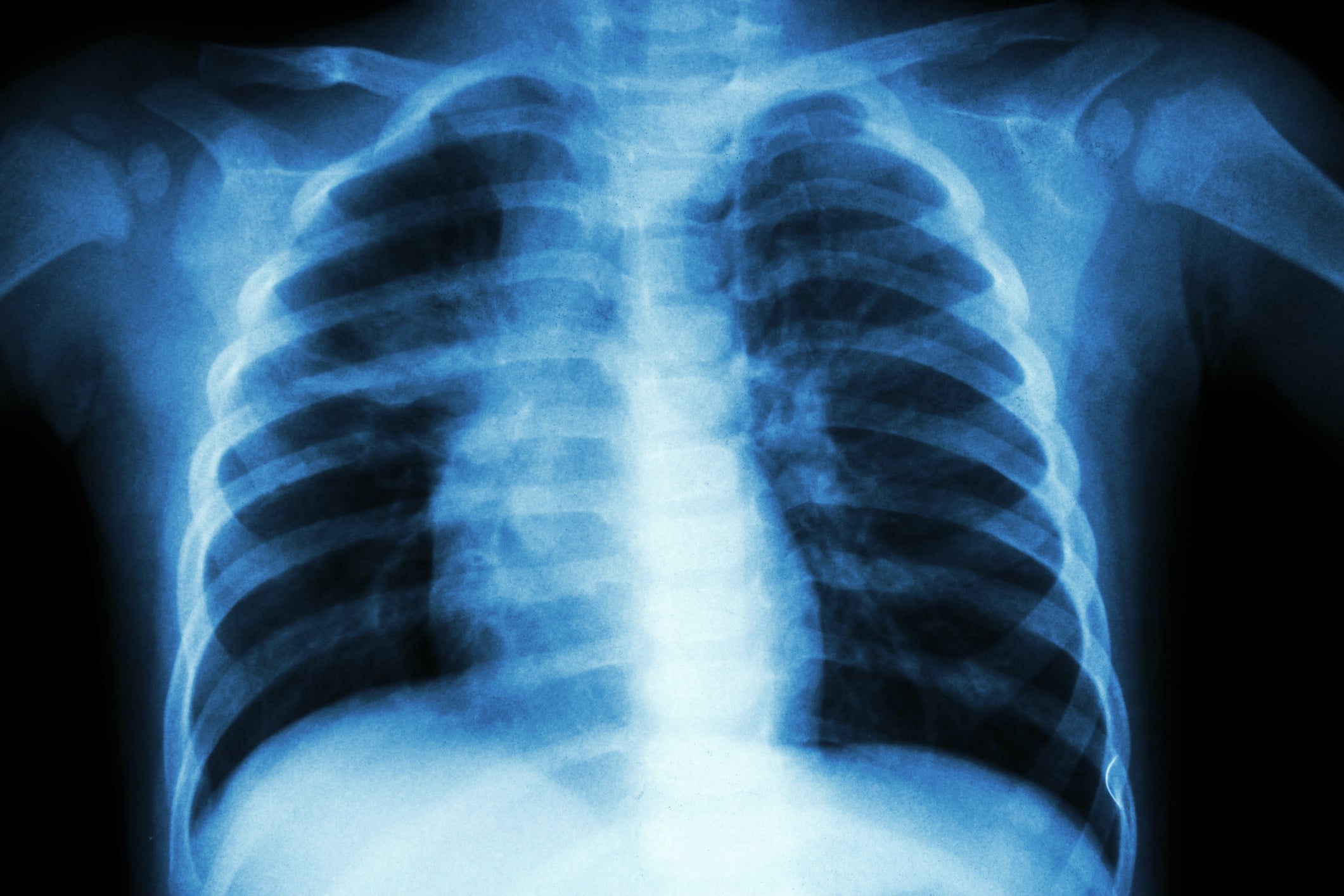

“Some people who have false positive diagnoses actually have some quite serious conditions that would benefit from prompt diagnosis and treatment,” such as pneumonia, lung cancer, or COPD, Menzies told NPR.

To understand the magnitude of TB misdiagnoses, Menzies and colleagues analyzed World Health Organization data on 6.8 million TB diagnoses across 111 countries in 2023. They estimated the number of false negatives and false positives using an assumed 25% rate of disease among individuals evaluated for TB, a rate based on a meta-analysis of TB diagnostics. The co-authors of the new study calculated that more than two million people received a false positive diagnosis and one million people received a false negative diagnosis.

According to Menzies, false positives likely result from “the challenges that clinicians—mostly those working within weaker health systems in low- and middle-income countries—face when diagnosing patients who they think might have TB.” Many TB rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) have poor sensitivity and can produce false negatives. Meanwhile, clinicians assessing patients’ symptoms and making their best medical guess of TB can result in false positives.

“Clinicians may be making the best decision for the patient, but the diagnostics they are using have big deficiencies,” Menzies explained. “Without changing the technology available, the only way to reduce false positive diagnoses would be to treat fewer of these individuals with an unclear diagnosis, which would increase false negative diagnoses.”

The researchers wrote that a combination of adopting improved RDTs and improving clinical diagnosis guidelines offers the best odds to tackle both false negatives and false positives. Overall, however, they stressed the need for ongoing and increased investment in the development of higher-sensitivity TB diagnostic tests that can reduce the need for other methods of diagnosis.

Read the NPR article:

TB or not TB? That is the question