The 2025 Gen Z Uprising in Nepal: A Three-Part Analysis

Part 1: Anatomy of Nepal’s Gen Z Revolution

On September 8, 2025, for the first time in Nepal’s modern political history, mass civilian deaths occurred in an anti-corruption movement that carried neither party banners nor ideological manifestos.

Instead, the movement was driven by a leaderless network of young students, coordinated through digital platforms and united by frustration over corruption, censorship, and unaccountable governance.

The state’s response on September 8 constituted one of the most severe episodes of violence against civilians in Nepal’s post-1990 democratic era. The gathering that day was widely expected to be non-violent given that it was composed mostly of teenagers and students in school uniforms and because public protest had long been an institutionalized feature of Nepali civil society. Instead, it became the deadliest single day in Nepal’s democratic history, claiming the lives of more young, unarmed civilians on a single day than during the entire 2006 pro-democracy movement.

By the end of September, at least 75 civilians had been confirmed dead and over 2,000 injured.

By the end of September, at least 75 civilians had been confirmed dead and over 2,000 injured. The majority of fatalities resulted from gunshot wounds inflicted during clashes between demonstrators and security forces; forensic and medical reports indicate that nearly all gunfire victims were struck above the waist, primarily in the head, neck, and chest, strictly violating crowd control protocols. Several deaths also occurred as a result of arson-related incidents during the rioting, with victims trapped in government buildings, shops, and residential structures that were set ablaze. Emergency responders struggled to reach affected areas as daytime curfews paralyzed much of Kathmandu, and health facilities were overwhelmed by the influx of patients. Tear gas was deployed at Civil Service Hospital, where victims were being brought for treatment, further worsening the humanitarian situation.

This three-part analysis examines the 2025 Nepal uprising through three central questions:

- Part 1: What were the immediate triggers and key events of the movement that led to the government’s collapse?

- Part 2: What pre-existing structural and economic fractures, along with weaknesses in digital governance made Nepal vulnerable to this crisis?

- Part 3: How can geospatial technologies be leveraged for civilian protection and atrocity prevention in Nepal?

Origins of the Protest Movement

Public discontent in Nepal reached a boiling point on September 4, 2025, after the government banned 26 social media platforms for failing to comply with its registration requirements. The move was the final spark for a public already enraged. For months, a viral trend on social media (#NepoBaby) had brought widespread attention and commentary on the strong disparity between the lavish lifestyles of politicians and their families and the public that had long been frustrated by rampant corruption, unemployment, and human capital flight; this Gen Z movement had already spread through Indonesia, the Philippines, and Bangladesh. Following a pattern seen across Southeast Asia, this online movement finally erupted into the streets of Nepal when the government pulled the plug on their primary means of expression.

The requirements for social media registration were rooted in the Social Media Management Directive 2080 in November 2023, under the authority of the Electronic Transaction Act 2063, which required digital platforms serving Nepalese users to register locally by establishing a physical presence in the country and appointing grievance and compliance officers to monitor content and ensure legal accountability. Despite multiple warnings and diplomatic outreach, most platforms did not meet the registration deadline of 28 August 2025.

Officials framed the shutdown as a long-overdue regulatory intervention, arguing that unregistered platforms had become breeding grounds for hate speech, coordinated misinformation campaigns, online harassment, and content that could incite violence. However, critics said the ban went far beyond routine regulation and was aimed at silencing online dissent.

As anger moved from social media to the streets, several locations across the Kathmandu Valley quickly became the main arenas of confrontation. The protests began at Maitighar Mandala, a major roundabout and a site of public demonstrations in central Kathmandu, before moving east toward New Baneshwor and the Federal Parliament Building via Bijuli Bazaar. As the unrest widened, curfews were imposed around Shital Niwas (the President’s Office) and Singha Durbar (central administrative complex of the Government of Nepal), while violence also spread to Balkot in Bhaktapur, the area surrounding former Prime Minister Oli’s private residence.

Timeline of Nepal’s Gen Z Movement:

September 8, 2025: The Protest and Initial Crackdown

- 9:00 a.m. – Thousands of young protesters began gathering at Maitighar Mandala in central Kathmandu to rally. By 9 a.m., the Maitighar intersection was filled with school and college students (many in uniform) and young professionals carrying banners like “Youth Against Corruption.” Some students were also seen waving anime One Piece flags.

- 10:00 – 11:00 a.m. – As crowds grew, protesters marched east toward New Baneshwor, singing patriotic songs along the way. By 11:38 a.m., demonstrators breached the first police barricades, prompting security forces to deploy water cannons. Tear gas followed at 11:55 a.m., and by 12:08 p.m., around twenty individuals had climbed the main gate of the Federal Parliament.

- 12:30 p.m. – The Kathmandu District Administration Office imposed a curfew in New Baneshwor and surrounding areas, though much of the crowd could not hear the announcement. At 12:37 p.m., police opened fire for the first time, targeting protesters who had climbed onto the terrace of a small building near the Parliament gate.

- 12:45 – 2:00 p.m. – By 12:50 p.m., a dense crowd had formed near the west-facing Parliament gate. At 12:57 p.m., protesters climbed a police checkpost inside the Parliament compound, and at 1:20 p.m., a Naya Patrika journalist was shot while reporting. Injured protesters were transported to the Civil Service Hospital as several vehicles burned outside and at least one ambulance was damaged.

- 2:30 – 3:30 p.m.– Around 3:00 p.m., police entered the Civil Service Hospital premises and fired tear gas inside the compound. By 3:30 p.m., preliminary reports confirmed fourteen fatalities.

- 5:00 – 6:00 p.m. – By early evening, officials reported nineteen protesters killed and more than 100 injured. Prime Minister Oli convened an emergency cabinet meeting at 6:00 p.m.

- 8:00 – 11:30 p.m. – Home Minister Ramesh Lal Lekhak resigned at 8:00 p.m. Late that night, at 11:25 p.m., Communications Minister Prithvi Subba Gurung announced the lifting of the social-media ban that had sparked the protests. Curfews were expanded to Shital Niwas, the Vice-President’s residence, and the Singha Durbar complex. The army was placed on standby as unrest spread to other cities overnight.

September 9, 2025: Continued Unrest and PM Oli’s Resignation

- Morning – Despite curfews, fresh protests erupted across the country. At 10:07 a.m., Agriculture Minister Ramnath Adhikari resigned. Former Chief Justice Sushila Karki visited Civil Service Hospital at 10:36 a.m., followed by Health Minister Pradeep Poudel’s resignation at 10:45 a.m. By 11:42 a.m., former Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba’s residence had been set on fire, and around noon some members of Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP) announced their collective resignation. Offices of the Nepali Congress and CPN-UML were also torched.

- 12:30 – 1:00 p.m. – At 12:54 p.m., former Prime Minister Oli’s private residence in Balkot was set ablaze, followed six minutes later by the burning of Gagan Thapa’s home. Additional arson was reported at the Department of Transport Management and the Hilton Hotel in Kathmandu.

- 2:00 – 3:30 p.m. – Prime Minister Oli formally resigned from office. At 2:30 p.m., security officials publicly stated they had no authorization to open fire even if major government buildings were attacked. Fires then spread to the Supreme Court at 3:00 p.m., the Maoist Party headquarters at Paris Danda at 3:08 p.m., and later to the District Court and Special Court.

- 4:00 – 10:00 p.m. – Singha Durbar was reported to be burning heavily, and the President’s residence at Shital Niwas had also come under attack. Over 3,000 inmates broke out of Central Jail Sundhara between 8:00 p.m. and 10:00 p.m.

This detailed chronology of the September 8-9, 2025 uprising is synthesized from extensive ground reporting and an interactive map published by Onlinekhabar.

Constitutional Crisis and Interim Governance

In the aftermath of ex-PM Oli’s resignation on September 9, the Nepal Army invited representatives of the Gen Z movement for dialogue. During the meeting, Chief of Army Staff Ashok Raj Sigdel mentioned businessman Durga Prasai and the Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP) as stakeholders in the movement, which prompted several Gen Z representatives, including Rakshya Bam, to walk out. According to Republica’s reporting, Bam stated outside Army Headquarters that the Army Chief had instructed them to meet the President and participate in negotiations together with Durga Prasai and the RSP faction. She said the delegates believed that being grouped with them would undermine the credibility of their movement, so they refused the proposal and left the meeting.

Shortly after, on a Discord server called “Youth Against Corruption” with over 145,000 members, more than 10,000 users met virtually to debate potential candidates through hours of discussion, multiple polls, and the use of sub-channels for fact-checking. Five names were shortlisted for the final voting: Harka Sampang, a social activist and mayor of Dharan; Mahabir Pun, a popular social entrepreneur and activist running the National Innovation Centre; Sagar Dhakal, an independent youth leader; advocate Rastra Bimochan Timalsina (known as Random Nepali on YouTube); and former Chief Justice Sushila Karki. An open Discord poll drew 7,713 votes, with Karki receiving 3,833 votes (50 percent).

The selection process involved three days of hectic negotiations, with sharp differences among different groups over appointing Karki as prime minister. While President Ramchandra Paudel was adamant about staying within constitutional bounds, Gen Z youths were frustrated over what they saw as unnecessary delays, with differences centering on whether and when to dissolve Parliament. On September 12, President Ram Chandra Poudel appointed Karki as interim Prime Minister under Article 61(4) of the Constitution of Nepal, making her the country’s first female head of government. Upon her recommendation, Poudel dissolved the 275-seat parliament and set elections for March 5, 2026, approximately two years earlier than planned.

The immediate appointment of former Chief Justice Sushila Karki to the Prime Minister’s office triggered a constitutional dispute, as the decision raised a prima facie contradiction with Article 132(2) of the Constitution of Nepal. This provision explicitly states that any individual who has once held the office of Chief Justice or a Judge of the Supreme Court “shall not be eligible for appointment to any government office, except as otherwise provided in this Constitution.” This clause is a foundational provision designed to maintain the strict separation of powers and protect judicial independence by preventing the executive branch from offering future positions to members of the judiciary.

In defense of the appointment, legal experts including prominent constitutional lawyer Bipin Adhikari advocated for a pragmatic interpretation of the constitution in light of the extraordinary circumstances. Adhikari did not dispute the textual conflict with Article 132 but argued that the nation’s stability and the imperative to resolve a deadly political vacuum justified the move. His defense rested on the doctrine of necessity, suggesting that an action technically violating a specific clause could be permissible to save the constitutional order from total collapse.

Human Rights Violations

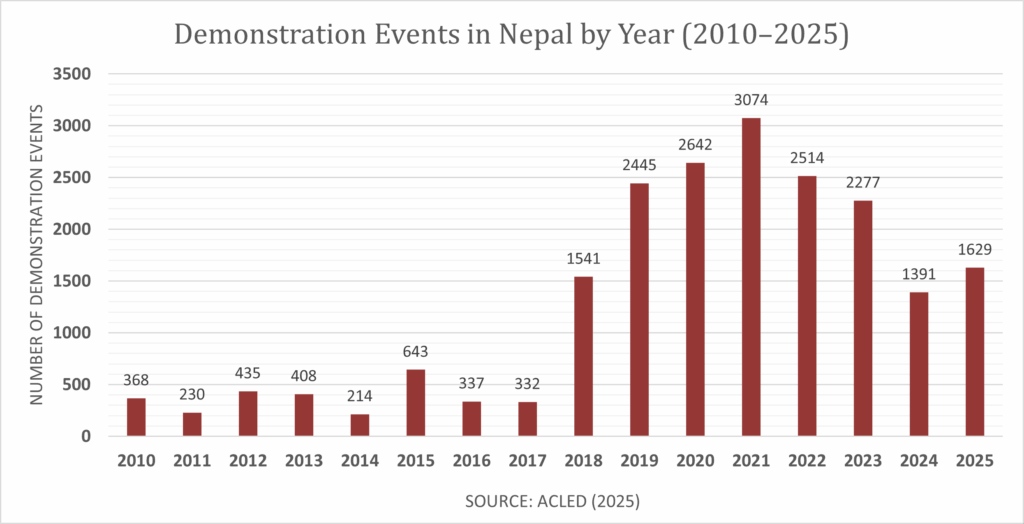

The ACLED data (Figure 1) show that public demonstrations have been a defining feature of Nepal’s political landscape for over a decade, peaking during moments of transition such as the 2015 constitutional crisis and the 2020–2021 parliamentary disputes. Still, the violence against civilians seen on 8 September 2025 was unusual.

Police logs revealed that 13,182 rounds of ammunition had been fired over the two days- 2,642 live bullets, 1,884 rubber rounds, and 6,279 tear-gas shells.

The Model Protocol for Law Enforcement Officials, endorsed by UN special rapporteurs, states that police should facilitate and protect assemblies, use negotiation and communication to de-escalate tensions, and give clear warnings and safe avenues for dispersal before resorting to force. It also calls for civilian‑led oversight and special care when children are present. These standards were not followed on September 8th’s protest.

Nepal’s Ministry of Health and Population confirmed the death of a 12-year-old student, and at least nineteen students were reported killed that day alone. A forensic report prepared by Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital confirmed that nearly all gunshot victims were struck above the waist, primarily in the head, neck, and chest. Police logs revealed that 13,182 rounds of ammunition had been fired over the two days—2,642 live bullets, 1,884 rubber rounds, and 6,279 tear-gas shells—in violation of Nepal’s own crowd-control regulations, which requires warnings before fire and mandates that any live rounds be aimed below the knee. These actions also contravened the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms, which limit the use of lethal force to instances of imminent threat to life and require proportionality and precaution.

Simultaneously, mass prison breaks across 28 facilities resulted in 14,043 inmates and juvenile detainees fleeing custody; despite intensive operations, over 5,000 individuals remain at large. Over 1,200 police firearms—including INSAS rifles, SLRs, and service pistols—along with roughly 100,000 rounds of ammunition, were looted from police barracks and government offices during the unrest. As of early November 2025, more than 500 of these weapons and a significant portion of the ammunition remained unaccounted for.

Nepal’s security agencies such as Nepal Police, the Armed Police Force, the Nepali Army, and the National Investigation Department have identified escaped inmates and stolen weapons as the country’s most serious security threats ahead of the March 5 parliamentary elections. Joint patrols by the army, police, and armed police have been deployed nationwide in an attempt to restore public confidence, stabilize local conditions, and deter armed groups or criminal networks seeking to exploit the situation. However, more than 400 police stations and offices were burnt or destroyed during the unrest, forcing many units to operate from damaged or temporary structures. The Armed Police Force reported damage to 62 of its facilities, and Nepal Police estimated losses of personnel property alone at over Rs 220 million (US $1.5 million).

These incidents have drawn increased scrutiny from international human-rights organizations. The World Organization Against Torture (OMCT) and CIVICUS urged Nepal to lift curfews, withdraw the military and conduct prompt, impartial investigations. Human Rights Watch emphasized that the use of firearms in crowd control is unjustified. Given the security crisis and eroded public trust, the imperative for transparent and impartial investigations becomes urgent and non-negotiable.

Part 2 of this series will present a macro-level analysis of the structural factors that increased Nepal’s vulnerability to conflict in 2025, focusing on rapidly changing digital-information systems and long-standing development constraints.