How Lucian Leape inspired a patient safety movement

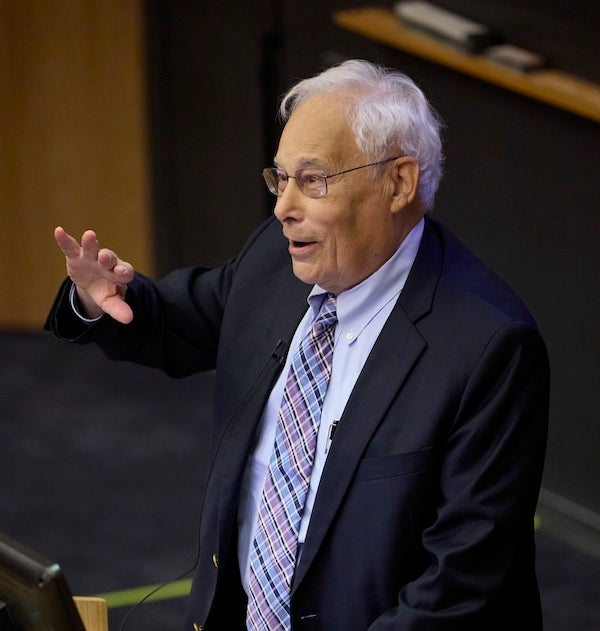

Physician and researcher Lucian Leape was convinced that, to reduce medical errors, the key wasn’t to punish surgeons, doctors, and nurses. Instead, it was to acknowledge that errors were bound to occur because all humans make mistakes, and to create systems that would make them much less likely to happen.

It was this belief—controversial at the time Leape championed it in the early 1990s, because doctors didn’t want to talk about their mistakes—that inspired a generation of researchers and clinicians in the burgeoning patient safety movement, according to experts who spoke at an Oct. 27 symposium in Leape’s memory at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Leape, who served for nearly three decades as an adjunct professor in Harvard Chan School’s Department of Health Policy and Management (HPM), died in June 2025 at age 94. At the event—held in Harvard Chan’s Kresge Auditorium and co-hosted by HPM—nearly a dozen experts, many of whom knew and worked with Leape, discussed his legacy, the trajectory of the patient safety movement, and paths forward in the field.

In opening remarks, Meredith Rosenthal, C. Boyden Gray Professor of Health Economics and Policy and HPM chair, credited Leape for his “incredible dedication and fearlessness.”

Atul Gawande—surgeon, author, and distinguished professor in residence at Harvard Chan School’s Ariadne Labs—was a keynote speaker at the event. He said that Leape “helped transform medicine’s moral self-conception from one that prized perfection and regarded error as failure of character to one that prized humility and understanding failure.”

Gawande offered an overview about Leape’s career, calling it “a study in audacity and late blooming.” Leape spent many years as a successful pediatric surgeon, then, at age 56, did a fellowship at the Rand Corporation focused on epidemiology and health policy. After that, in 1988, he made the risky decision to switch careers to become an adjunct professor at Harvard Chan School, a position he held through 2015.

Patient safety movement kicks off

At the invitation of then-Harvard School of Public Health Dean Howard Hiatt, Leape joined a project called the Harvard Medical Practice Study that investigated the medical malpractice system by looking at the records of more than 30,000 patients admitted to 51 hospitals in New York state in 1984. The result of the investigation was a series of papers in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1991. One paper shed light on just how rampant medical errors were—it documented that adverse events or complications occurred in 1 in 27 patients, and 15% of those resulted in death. Another paper found that providers were rarely held accountable for these adverse events by the medical malpractice system.

The studies’ findings propelled Leape to learn what was behind all the medical errors. He and colleagues took another look at the patient records and found that most errors were not due to ignorance or negligence, but simply due to humans making preventable mistakes—such as medication errors made because of illegible script.

In 1994, Leape published what Gawande called a “blockbuster” in the Journal of the American Medical Association titled “Error in Medicine.” In the paper, Leape argued that adequately addressing the problem of medical errors would require a shift away from a focus on individual accountability and toward a focus on systems improvements. “As he explained, all humans err frequently,” Gawande noted. “Systems that rely on error-free performance are therefore doomed to fail.” Leape outlined approaches used to prevent errors in other industries such as the airline and nuclear industries—including things like checklists, standardized processes, redundancies, and feedback loops—that would “make things easier to do right and harder to do wrong,” Gawande said.

The same month the JAMA piece was published, a high-profile case in Boston—the death of 37-year-old Boston Globe reporter Betsy Lehman at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute from a fourfold overdose of chemo for her breast cancer—brought national attention to the issue of medical errors. In the wake of Lehman’s death, a number of Dana Farber employees—oncologists, pharmacists, nurses—either lost their jobs, were reprimanded, or were put on probation. But Leape spoke out against these actions in a Boston Globe opinion piece, making the point that punishment would drive clinicians to cover up errors. He argued that “the focus needed to be on the system flaws that failed the patients as well as the clinicians,” Gawande said.

Later, Leape went on to work with Don Berwick, president emeritus and senior fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and colleagues at the Institute of Medicine to co-author a landmark 1999 report titled “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System.” The report outlined the magnitude of the problem of medical errors in the U.S., estimating that between 44,000 and 98,000 Americans were dying from them every year—the equivalent of three jumbo jet crashes every two days—and presented ways to combat the problem.

“The report galvanized action across the country and the world,” said Gawande, and it led to the creation of “an entire institutional ecosystem” surrounding patient safety. The movement also changed the course of Gawande’s career, spurring him to lead the development of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Surgical Safety Checklist, which would go on to reduce surgical complications and deaths worldwide by more than a third.

Berwick—another keynote speaker at the symposium—noted that while Leape was not the first to call attention to the problem of patient safety, he was the one who started the movement. “Everyone who knew Lucian knew about this kind of steely commitment to the truth, even the uncomfortable truth,” Berwick said. “And because of that, there’s a patient safety movement. And thousands of patients are alive today [because of it], and there will be thousands and thousands more ahead.”

Forging ahead

One of the symposium’s panels focused on paths forward in the patient safety field. Eric Schneider, adjunct professor of health policy and management at Harvard Chan School, said that while there has been much progress in improving patient safety, there is still work to be done. According to recent estimates from WHO, for example, roughly 1 in every 10 patients is harmed in health care, yet more than 50% of that harm is preventable.

Michaela Kerrissey, associate professor of management at Harvard Chan School, noted that Leape’s legacy set the stage for her research on workplace psychology safety—an environment where people feel they can be candid and that issues they bring up will be discussed. Kerrissey and her colleagues measure psychological safety in work settings, figure out when and why people are able to bring up safety issues and do something about them, and learn what holds people back from doing so.

Patricia Dykes, senior nurse scientist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Patient Safety Research and Practice—who has done research aimed at preventing falls among patients—said the focus on keeping patients safe should be on learning and improvement, not punishment or fault. If harm occurs, she said, “People have to feel safe to be able to talk about what happened, [to ask] how do we learn from this, how do we make sure that this doesn’t happen again?”