Mapping Safety and Preventing Violence: Lessons for Atrocity Prevention

Red Dot Foundation and the Safecity Platform

Atrocities rarely begin with mass killings. One of the earliest warning signs is gender-based violence (GBV). Sexual assault, domestic abuse, forced marriage, and harassment are not only grave human rights violations in their own right, but they also reveal the deeper structural inequalities that can spiral into broader persecutions and mass atrocities, if left unchecked. GBV exists on a continuum of violence and recognizing its patterns is critical to prevention. Data, when used responsibly, can help communities identify risks and intervene early. Red Dot Foundation (RDF) is one such organization, combining spatial analysis with an understanding of local social norms to address GBV and strengthen community resilience.

RDF developed Safecity, a crowdsourced platform and movement that collects, analyzes, and visualizes anonymous reports of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) to make public spaces safer for women and marginalized communities. Built at the intersection of gender rights, technology, and urban planning, Safecity’s methodology turns invisible experiences into actionable insights for individuals, communities, and institutions.

Safecity in Faridabad: From Data to Action

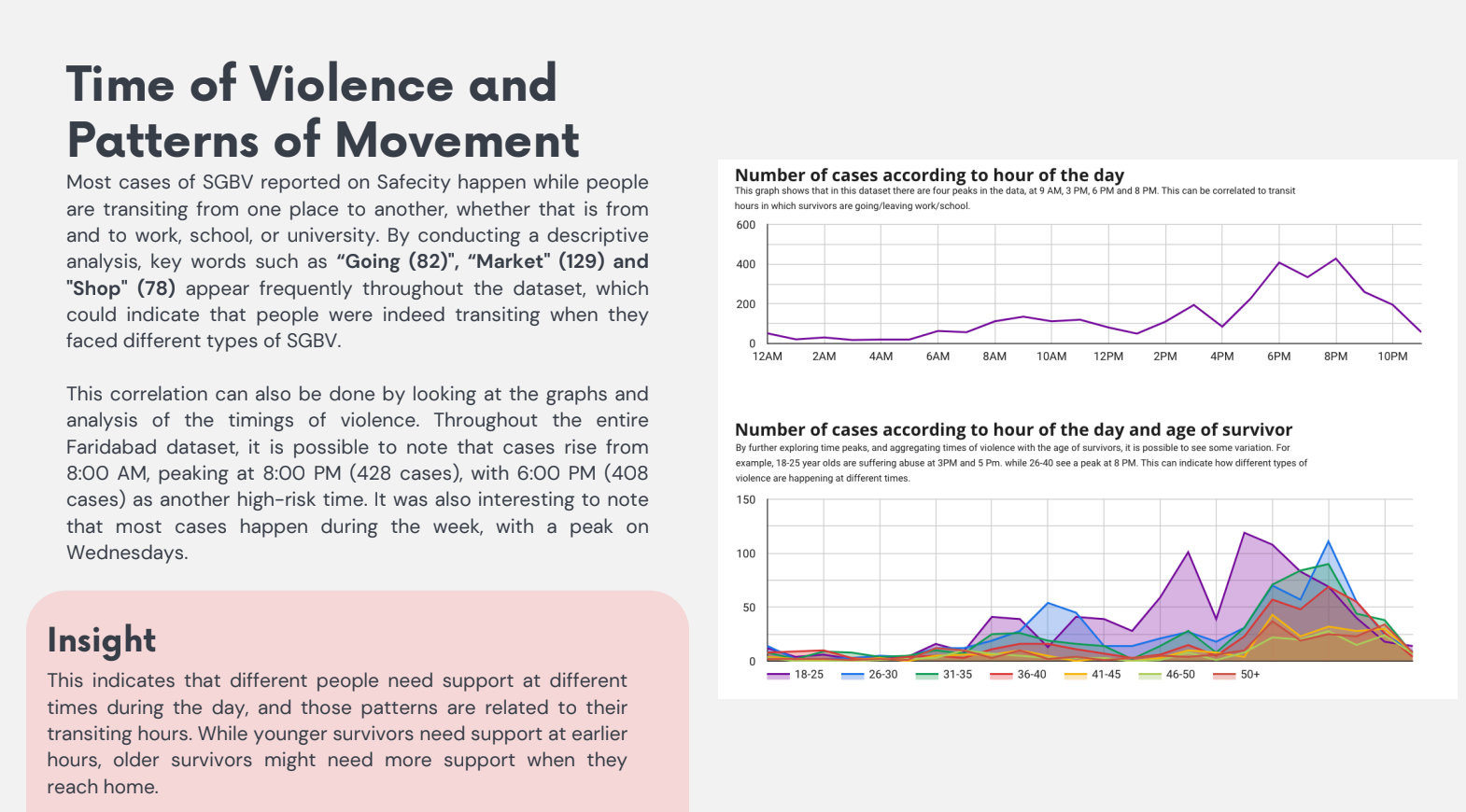

In October 2023, in Faridabad, India, Safecity piloted the Safer Faridabad project that demonstrated how anonymous community reporting, paired with institutional collaboration, can transform both public safety and survivor trust. The intervention began with safety audits and surveys conducted in identified hotspots, where over 4,000 narratives of unsafety and SGBV were collected. These narratives revealed everyday patterns of harassment such as stalking, catcalling, and indecent exposure, as well as less visible risks tied to alcohol and drug use in public spaces.

Geotagging and analyzing these reports allowed Safecity to visualize trends and create responsive programming to address emerging issues in the community. For example, while chain snatching and robbery were the most commonly reported crimes, categories like “other” began to surface new safety risks, such as harassment linked to intoxication and drug use. These insights were compiled into data dashboards and reports shared with the Faridabad police, turning invisible community experiences into actionable insights.

Community Engagement: Turning Data into Collective Action

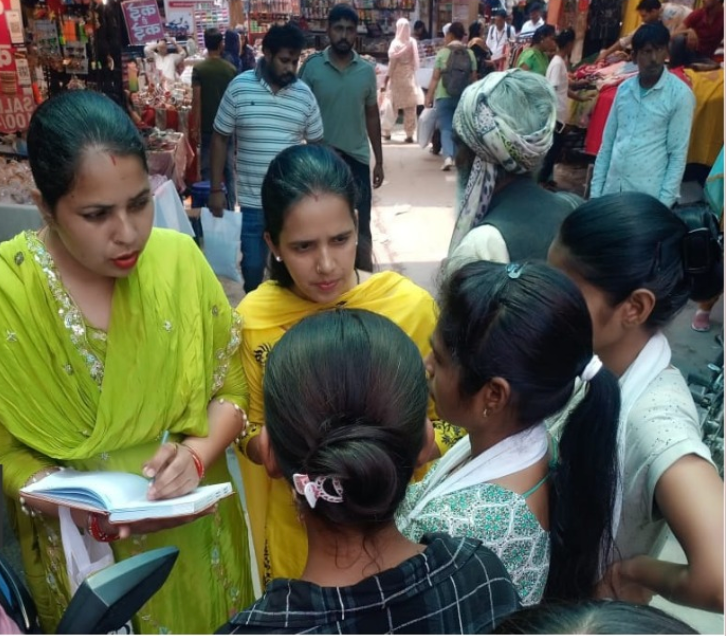

Safecity’s approach goes beyond data dashboards. After identifying hotspots through safety audits and crowdsourced reports, Safecity facilitators engaged directly with residents, schools, and civic groups.

Workshops and awareness sessions gave people space to reimagine public safety and to co-create solutions. Safecity’s “talking boxes” model (inspired by Polycom for Girls) also ensured inclusivity in contexts where digital access is limited. In communities without reliable technology, residents could drop paper reports into secure boxes, keeping reporting accessible and anonymous.

Safecity’s approach understands that technology alone cannot shift norms or restore trust. Any solutions to address GBV must be shaped by the lived experiences of those affected. Furthermore, data analysis must be combined with dialogue, empathy and local ownership to see sustained improvements in communities.

Collaboration with Police

One of the more novel contributions of this project is the meaningful engagement and partnership with local law enforcement to address GBV. The shift to a dialogue with the police–from passive dashboards to interactive feedback sessions–led to them reviewing reports not just as individual cases but as aggregated patterns that required systemic solutions.

When confronted with data showing low reporting rates, where only around 20% of survivors filed police reports, officers participated in empathy and survivor-centered training. Through role-play, they practiced small but meaningful shifts in interaction: offering water, asking questions with compassion, and avoiding victim-blaming. Over a three-month period, intent to report to police increased by 30%, highlighting how community engagement combined with responsive police training could directly influence survivor trust.

In response to trends emerging under reports categorized as “other,” police deployed CCTV cameras in areas where drug and alcohol use correlated with higher harassment incidents, demonstrating how community data could drive rapid preventive action.

Traditional policing often responds after an incident has happened. The project differed a lot because we focused on prevention, presence and listening to people.

Quote from an interview between Signal Team and Safecity Team on July 23, 2025

Lessons Learned

The Faridabad project underscored several key insights:

- Movement patterns matter. Violence correlates with how people navigate public spaces; peaks in harassment reports often coincided with typical transit times.

- Legal clarity drives reporting. Clear-cut crimes like robbery are more frequently reported than intimate violations such as indecent exposure, where stigma and legal ambiguity remain barriers.

- Trust is foundational. Survivors may not seek linear justice; many want safety and dignity over a formal legal process. Empathetic policing helps close this gap.

- Community input is essential. Safecity’s strength lies not in its technology alone but in combining crowd-mapped data with community voices and institutional accountability

Why This Matters for Atrocity Prevention

Gender-based violence does not exist in isolation and often foreshadows broader communal violence. Safecity’s work in Faridabad illustrates how addressing GBV through data-driven, community-informed interventions can strengthen atrocity-prevention toolkits. By turning individual experiences into systemic insights, Safecity helps both communities and institutions respond before violence escalates. In centering survivor voices and using data to build trust, Safecity offers a replicable model for bridging the gap between communities and institutions in fragile contexts.

This article represents the independent analysis of the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative’s Atrocity Prevention Lab and Red Dot Foundation and does not reflect the official views of the Haryana Police or the Government of Haryana.

We would like to thank SafeCity members ElsaMarie DSilva, Camila Gomide, Sonali Alves, Soumyaa Hariharan, and Tania Echaporia for their input.

Shwetha Srinivasan is a current Research Assistant at the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative’s Signal Program on Human Security and Technology.