Why more stringent regulation is needed for ‘forever chemicals’

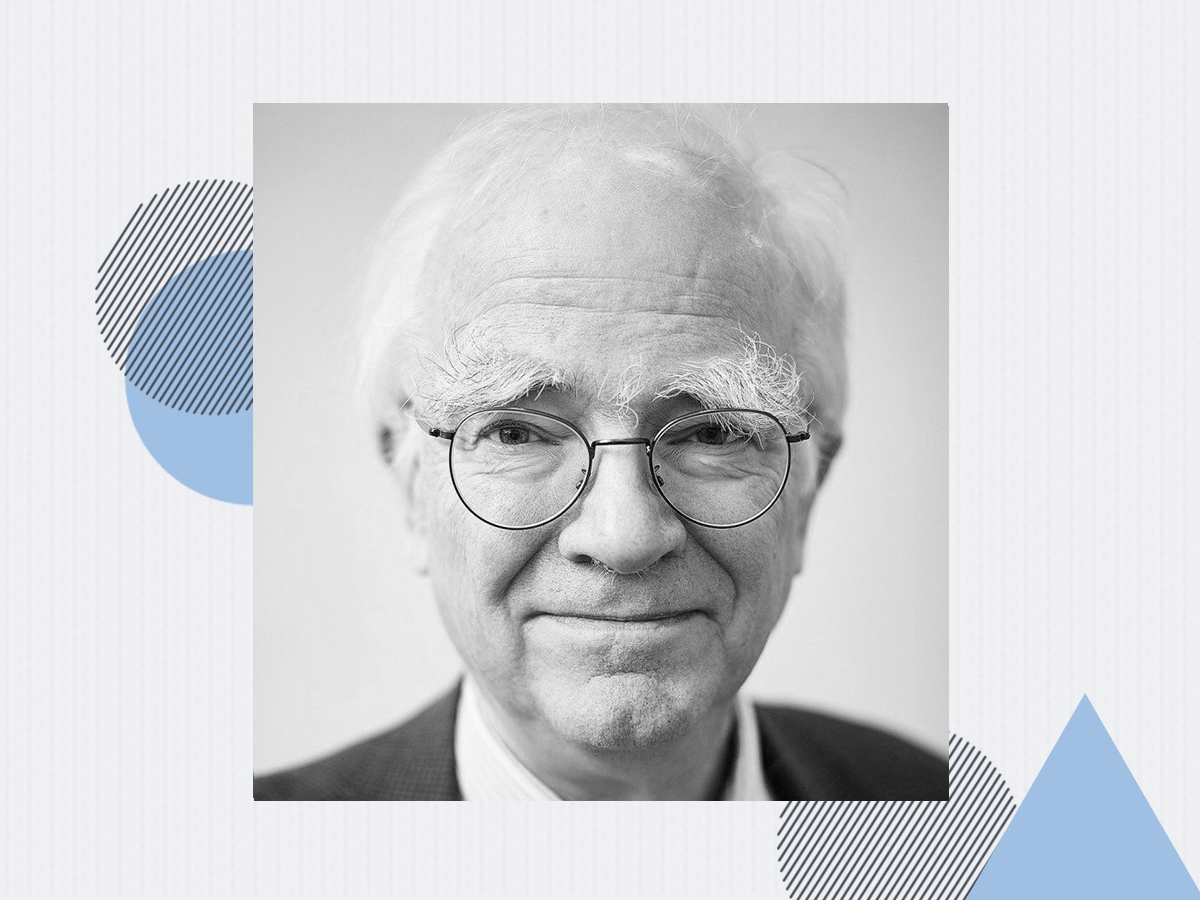

January 4, 2022 – The Biden administration recently announced a plan to set enforceable drinking water limits on certain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—long-lasting, man-made chemicals that are used in a wide range of consumer products and that are known to pose health risks to millions of Americans. Philippe Grandjean, adjunct professor of environmental health at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, discusses the importance of regulating PFAS.

Q: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says it plans to establish a national drinking water standard for certain PFAS chemicals by March 2023. What do you think of the plan?

A: I’m thrilled about it. Any support we can conjure for the EPA to get going is good, because we’re so far behind in limiting the use of these dangerous chemicals. PFAS are used in many products, such as waterproof clothing, nonstick cookware, firefighting foams, cosmetics, food packaging, cleaning supplies, and electronics. We know that the blood of nearly all Americans contains some PFAS, which we call “forever chemicals” because they don’t break down in the body. And we’ve shown with two decades of intensive research that PFAS are linked to serious health issues such as kidney and testicular cancer, weakened immune system, endocrine disruption, fertility problems, and decreased birth weight.

The European Union (EU) is way ahead of the U.S. on regulating PFAS. In September 2020, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) set a new safety threshold for the four most common PFAS. The EPA’s limit is for only two PFAS—PFOS and PFOA—and it’s more than 30 times higher than the European limit, and it pertains only to drinking water. So that illustrates how far behind the U.S. is.

In setting their limit, the EFSA took into account toxicity to the immune system posed by PFAS, which is expressed by lowered antibody responses to childhood vaccines—an effect that we first reported in JAMA in 2012. The EFSA’s exposure limit is meant to ensure that women of reproductive age do not accumulate too much of a PFAS burden. The strategy makes sense, in my opinion, because PFAS compounds tend to pass through the placenta during pregnancy, so that a mother will share her accumulated burden of these compounds with the next generation. In addition, our 2015 study found that when the mother is breastfeeding—something that is strongly recommended by the CDC and WHO—these compounds are excreted through human milk. The infant may reach a blood concentration of PFAS that is 10-fold higher than the mother’s. And this happens at the most vulnerable stage of life, when various organs and biochemical functions are being fine-tuned. If something goes wrong at this stage, it will likely stay with us for the rest of our lives and affect our disease risks later on.

For example, in a study we published recently, we found that, even in nine-year-old children, their accumulated PFAS exposures were associated with elevated cholesterol, an outcome that was thought only to affect adults. And people who have high cholesterol as children or young adults are also likely to have high cholesterol later in life.

Q: The EU regulated four PFAS, but not others. Why?

A: The EU decided to look at those four because they are so-called “legacy” PFAS, about which there is substantial documentation. They didn’t address the field of substitutes—new potential compounds that might enter the environment in the future. But we have to face this problem at some point. These compounds are so useful that, if industry realizes there’s a certain compound they can’t use, they will immediately look for alternatives. That’s my concern, and many of my colleagues have the same concern: that if the physical and chemical properties of the substitutes are the same, they may have the same toxicological problems as the legacy chemicals.

One positive development in the U.S. is that, in late December, the EPA granted a petition from six North Carolina public health and environmental justice organizations to compel companies to conduct toxicity testing of additional PFAS. It’s a step in the right direction.

Q: Given that substitutes may be dangerous, what do you think governments should do in terms of regulating PFAS?

A: I’m willing to accept that some PFAS compounds may pose fewer human health risks. But I would like to see the proof of their safety before they’re allowed to be used in products, rather than finding out 10 to 15 years down the road that these compounds don’t break down in the body, that they accumulate, and that women pass them down to their children via the placenta or through breastfeeding.

We should not do this experiment again on humanity. Industry has hidden the dangers of PFAS from us for decades. They knew about PFAS toxicity since the 1970s but didn’t share the information with the EPA until 2000. We should not allow similar secrecy to happen again.