Cancer symposium looks at new diagnostics for early detection

February 12, 2020 – Timothy Rebbeck kicked off the second annual Zhu Family Center for Global Cancer Prevention symposium on an optimistic note. “U.S. cancer rates have dropped dramatically. In 2016-2017, we saw the largest single-year decline in cancer deaths ever,” he told the dozens of attendees. “That’s an incredible thing to say.”

But Rebbeck, director of the Zhu Family Center for Global Cancer Prevention and Vincent L. Gregory, Jr. Professor of Cancer Prevention at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, quickly added there’s much more work to be done. The global burden of cancer remains staggering and it’s getting worse, he said. By 2030, there could be as many as 13 million cancer deaths around the world each year, and low- and middle-income countries will be especially hard hit. Key to reducing suffering and death associated with cancer, Rebbeck said, is improving efforts to prevent cancer and detect it as early as possible.

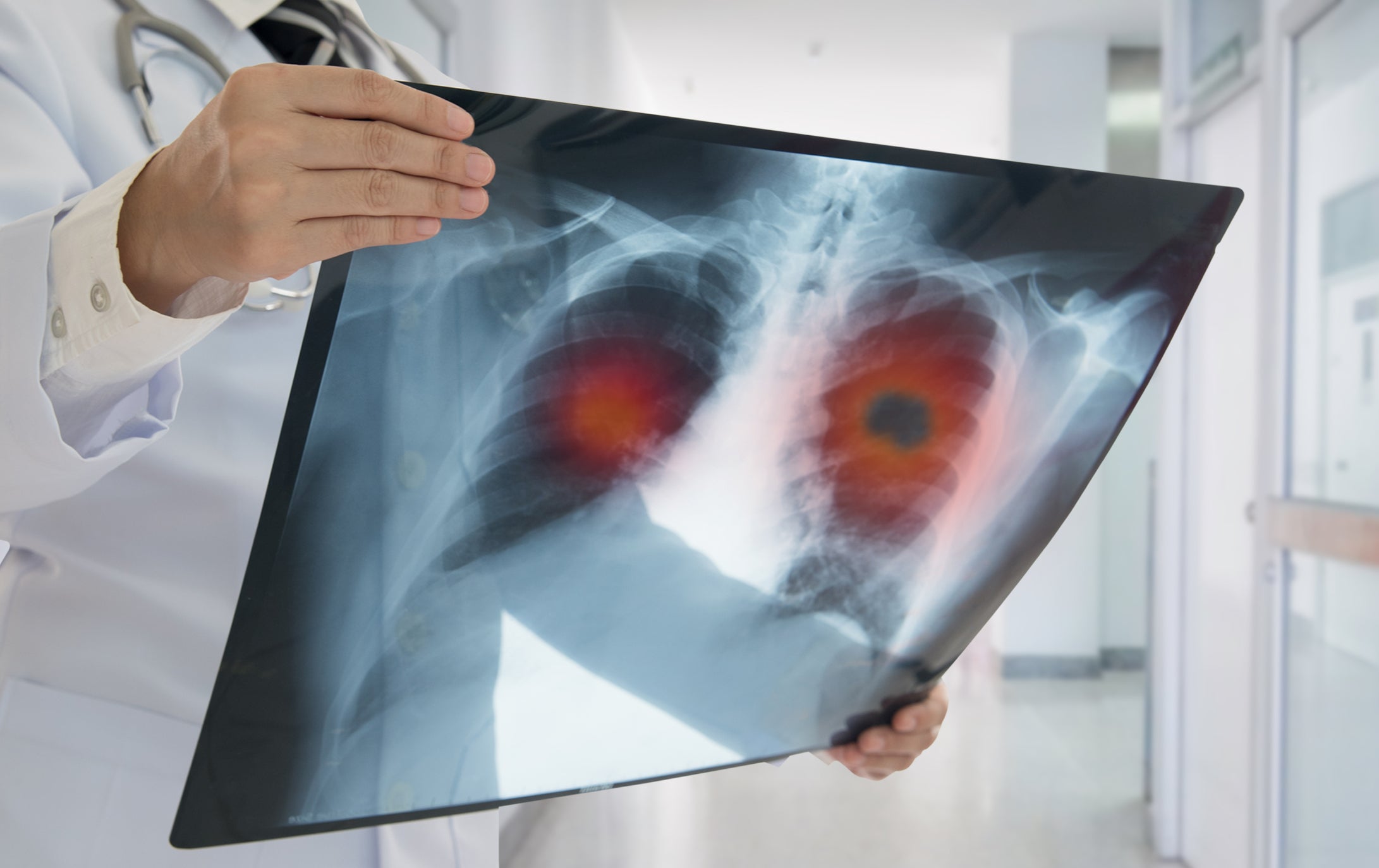

The symposium, “Novel Diagnostics for Early Cancer Detection,” was held on February 5, 2020 at the Joseph B. Martin Center. The event brought together experts from around the world and across disciplines to discuss efforts to build better diagnostic tools for myriad cancers. Over the course of the day, researchers discussed both technological and biological challenges to improving cancer diagnostics, as well as social and economic factors that can impede progress—and innovative ways of overcoming these challenges.

Among the presenters was David Walt, Hansjörg Wyss Professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard Medical School, who discussed his efforts to move away from genetics and genomics for cancer diagnostics and focus instead on patterns of protein expression as a possible way of detecting cancers earlier.

Lecia Sequist, director of the Center for Innovation in Early Cancer Detection at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), delivered a presentation showcasing various efforts of researchers at MGH to improve cancer diagnostics, including the use of artificial intelligence and deep learning to analyze huge volumes of mammogram scans for patterns in breast density that may signal a woman is at increased risk of breast cancer.

Sequist also discussed a project to improve uptake of current and effective lung cancer screening methods among patients with serious mental health issues. “This is very different than talking about a new technology or device,” she said, “but it’s really important to think of new ways to bring all patients in for cancer screenings.”

The symposium also included a moment to honor three Harvard Chan School researchers who received Prevention and Early Detection for Emerging Researchers (PEER) Awards to help them pursue cutting-edge approaches to detecting early stage cancers. The awardees were Jeffrey Miller, assistant professor of biostatistics; Lorelei Mucci, professor of epidemiology; and Xuehong Zhang, assistant professor in the Department of Nutrition.

The event wrapped up with a lively panel discussion in which attendees and presenters wrestled with numerous issues, including the fact that it can sometimes take more than a decade for new diagnostic approaches to be studied and vetted. But as Rebbeck noted in his opening remarks, there are plenty of reasons to be optimistic. “If we can continue to change the ways in which cancer is identified and diagnosed,” he said, “we can continue to make these large dents in the number of cancer deaths.”

photos: Kent Dayton