For immediate release: January 28, 2015

In some U.S. health plans, HIV drugs cost nearly $3,000 more per year than in other plans. If left unchecked, this practice could partially undermine a central feature of the Affordable Care Act.

Boston, MA ─ Some insurers offering health plans through the new federal marketplace may be using drug coverage decisions to discourage people with HIV from selecting their plans, according to a new study from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The researchers found that these insurers are placing all HIV drugs in the highest cost-sharing category in their formularies (lists of the plans’ covered drugs and costs), which ends up costing people with HIV several thousands more dollars per year than those enrolled in other plans.

The study appears online January 28, 2015 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Eliminating discrimination on the basis of preexisting conditions is one of the central features of the Affordable Care Act (ACA),” said Doug Jacobs, MD/MPH candidate at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and lead author of the study. “However, the use of formularies to increase costs and dissuade those with preexisting conditions such as HIV from enrolling in the plan threatens to at least partially undermine this goal of the ACA.”

Jacobs and senior author Benjamin Sommers, assistant professor of health policy and economics, analyzed what they call “adverse tiering”—in which all drugs for certain conditions are placed in the highest cost-sharing tiers—in 12 states in the federal marketplace. They compared plans in six states that had been mentioned in a complaint to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) about adverse tiering (Delaware, Florida, Louisiana, Michigan, South Carolina, and Utah), and in the six most populous states without insurers in the HHS complaint (Illinois, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Virginia). They compared cost-sharing for a commonly prescribed class of HIV medication—nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors, or NRTIs.

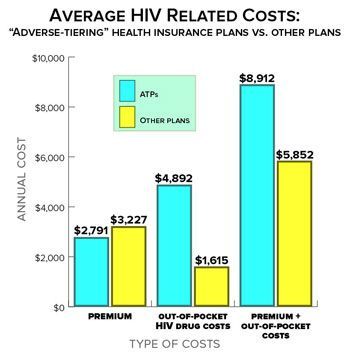

The researchers found that 25% of the plans examined used discriminatory drug tiering for NRTIs. The differences in out-of-pocket HIV drug costs between adverse-tiering plans (ATPs) and other plans were stark. People in ATPs on average paid three times more for HIV medications than people in non-ATP plans, with a nearly $2,000 annual difference even for generic drugs. Even though annual premiums in the ATPs tended to be lower than other plans, the high cost of HIV drugs in the ATPs meant that, on average, a person with HIV would pay $3,000 more for treatment each year than if he or she had instead enrolled in a non-ATP plan.

The researchers found that 25% of the plans examined used discriminatory drug tiering for NRTIs. The differences in out-of-pocket HIV drug costs between adverse-tiering plans (ATPs) and other plans were stark. People in ATPs on average paid three times more for HIV medications than people in non-ATP plans, with a nearly $2,000 annual difference even for generic drugs. Even though annual premiums in the ATPs tended to be lower than other plans, the high cost of HIV drugs in the ATPs meant that, on average, a person with HIV would pay $3,000 more for treatment each year than if he or she had instead enrolled in a non-ATP plan.

The researchers noted that insurers’ use of “adverse tiering” puts significant and unexpected financial strain on those with chronic conditions. They added that, over time, the practice could lead to sicker people clustering in plans that offer more generous prescription drug benefits—which could in turn create a “race to the bottom” in insurers’ drug plan designs as they try to avoid a large influx of sick enrollees that would negatively affect profits.

“The ACA has made a major positive change for people with preexisting conditions—they can now purchase insurance without paying higher premiums or getting denied coverage.” said Jacobs. “But some insurance companies seem to be setting up formularies that continue to discriminate against people with chronic conditions, and policymakers should consider steps to prevent these discriminatory practices in the future.”

“Using Drugs to Discriminate—Adverse Selection in the Insurance Marketplace,” Douglas B. Jacobs and Benjamin D. Sommers, New England Journal of Medicine, January 28, 2015, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1411376

Visit the Harvard Chan website for the latest news, press releases, and multimedia offerings.

For more information:

Todd Datz

tdatz@hsph.harvard.edu

617-432-8413

Photo: Shutterstock

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health brings together dedicated experts from many disciplines to educate new generations of global health leaders and produce powerful ideas that improve the lives and health of people everywhere. As a community of leading scientists, educators, and students, we work together to take innovative ideas from the laboratory to people’s lives—not only making scientific breakthroughs, but also working to change individual behaviors, public policies, and health care practices. Each year, more than 400 faculty members at Harvard Chan teach 1,000-plus full-time students from around the world and train thousands more through online and executive education courses. Founded in 1913 as the Harvard-MIT School of Health Officers, the School is recognized as America’s oldest professional training program in public health.