A life of exploration

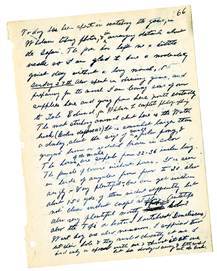

“The sun came out early and fiercely… As the hours wore on and noon was reached at times one felt the desire to become a little hysterical and to repress a scream and throw oneself into the forest at the side of the trail.”

So wrote Richard Pearson Strong in the 320-page diary he kept while leading the 1926–1927 Harvard African Expedition, which crisscrossed the remote interior of Liberia and then cut 3,500 miles across central Africa to end at Mombasa, Kenya.

A pioneer in researching tropical diseases, Strong arrived at Harvard in 1913, becoming the University’s first-ever professor of tropical medicine. Traveling, researching, and publishing at a preternatural pace, he packed several lifetimes’ worth of achievements into a single career, accumulating an encyclopedic knowledge of diseases that few Westerners would recognize: dengue and yellow fevers, leprosy, cholera, plague, Oroya fever, kala-azar, and various forms of dysentery.

His specialty was onchocerciasis, or river blindness, about which he published dozens of papers clarifying the infection’s natural history and transmission patterns, and described in detail black fly habitats and breeding cycles.

Between 1913 and 1938, Strong led five overseas expeditions to Africa and Central and South America. During World War I, he led a stunningly successful effort to control a typhus outbreak in Serbia.

Today, much of Strong’s legacy appears tinged by the endemic racism of his era. Announcing Strong’s appointment, for example, a University alumni bulletin article stated that one of science’s greatest services to mankind was “overcoming conditions which made life in the tropics almost impossible for white men and dangerous and enervating even to natives.”

Sweeping the field

In fall of 1973, residents on the island of Nantucket were treated to a curious sight: a lone scientist traipsing through underbrush, waving a giant white flag.

Its bearer, Andrew Spielman, wasn’t surrendering. Spielman, a vector-borne-disease expert at Harvard School of Public Health, was using the cloth to capture deer ticks—tiny arachnids he suspected of causing a human outbreak of babesiosis, a rare blood-borne disease that infected two Nantucket residents.

After weeks in the field, Spielman discovered that white-footed mice, a common species on the island, were often covered with larval ticks that carried the disease. Through careful analysis, Spielman showed that ticks like these were responsible for cases of human babesiosis, a malaria-like parasitic infection. Later research at Yale University revealed that the same ticks were spreading the newly identified Lyme disease, which had just begun to emerge in southern New England.

In response, Spielman began developing strategies to control the tick population, and by the late 1980s, stumbled on an ingenious solution with colleagues. They soaked cotton balls in pesticide, stuffed them into empty toilet paper rolls, and left them in the brush. Mice, which found the cotton irresistible for building nests, carried the pesticide back to their dens, where it killed off the ticks nestled in their skin. Within a single season, the researchers found, the number of deer ticks found on trapped mice had dropped by more than 90 percent.

Spielman’s groundbreaking work didn’t stop at ticks, however. His later research also helped identify mosquitoes as vectors for both the Eastern equine encephalitis virus and, later, for West Nile virus—a disease he suspected was carried in the blood of roosting birds.

Although Spielman personally tracked down the vector for a number of dangerous diseases before his death in 2006, he was always careful to frame his work within the larger context of public health. “I am not a mosquito specialist. I am not a tick specialist. I am a transmission specialist,” he mused in 1997. “That is what public health entomology is all about.”