April 20, 2016 – During the decade she spent as a physician assistant at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, Jill Roncarati saw, up close and personal, the ravages people suffered when they had no place to live. Cancers went undetected until they’d reached an advanced stage. Preventable complications from untreated diabetes emerged. Substance abuse problems dragged on for years.

Roncarati eventually decided the best way to help improve health among homeless people would be to study why they were faring so poorly—which led her to Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, where she earned a master’s of public health degree in 2007 and is now slated to earn a doctorate in social and behavioral sciences next fall.

Her doctoral research has focused on mortality rates and causes among the so-called “rough sleepers” in Boston—those who sleep outside for months at a time. “There hasn’t been a lot of research about this group,” Roncarati said. “I thought it would be important to really understand their situation in order to serve them best.”

Finding her calling

Roncarati studied psychology in college. Figuring she might work in the health care field, she also took courses in chemistry and biology. For several years after college she worked in biochemistry labs. But she wasn’t sure what she ultimately wanted to do.

One day in the mid-1990s, when she was working at Boston University School of Medicine’s Pulmonary Center, one of the pulmonologists invited her to shadow him for a day at Pine Street Inn, a Boston homeless shelter, while he conducted a tuberculosis (TB) clinic.

“We drove up in the back alley of Pine Street where he was parking his car, and I almost passed out from the smell of urine,” Roncarati recalled. “It was such an intense smell that I didn’t think I would be able to spend time with him there. But—surprisingly—I got used to it.”

In fact, she loved it. “Pine Street was this warm inviting place,” she said. “People were really collegial and enjoyed their work. And the patients were very appreciative when staff spent time with them and got to know them.”

Roncarati returned to Pine Street as a volunteer and eventually got hired as a TB outreach worker. She gave patients TB tests, explained the results, and described different treatment options. She learned other tools of the medical trade, too, like how to check blood pressure and vital signs.

A year and a half at Pine Street convinced Roncarati to become a physician assistant. After earning her PA degree she got a job at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP).

Concern for the sickest

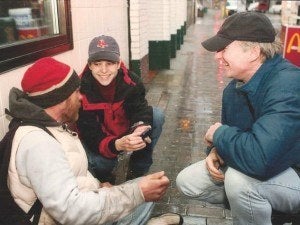

At BHCHP, Roncarati served on a “street team” that provided health care to the homeless population. They’d walk the streets of Boston several days each week, and once or twice a week they’d cruise around by van, seeking people out wherever they were—in alleys, under highway overpasses, on park benches.

“You got to know folks really well,” she said. “The homeless people we worked with knew the street team was out and about. We’d try to be a constant presence, to find out what they wanted or needed, and always looked for an opening so we could start conversations.”

Roncarati was especially concerned about the very sickest—those who spent night after night on the street, in the cold. Many of these rough sleepers struggle with addictions and avoid sleeping in shelters, where the rules are strict. “You can’t leave your bed to go outside during certain times, and many of these folks can’t go more than a couple of hours without a cigarette or a drink or a hit off of something,” Roncarati said. For some with severe mental illness, their paranoia keeps them outside.

Back to school

Frustrated by the gaps in the literature about the homeless, Roncarati decided that learning how to conduct her own research would be the best way to make “a lasting and positive impact.” She began studying at Harvard Chan School in 2005—and almost immediately felt she’d come to the right place. She found valuable mentors, like epidemiology professor Fran Cook, who’s given her practical advice on study design and analysis. Glorian Sorenson, professor of social and behavioral sciences—a “constant supporter” for the past 10 years—has provided crucial guidance as Roncarati worked on her dissertation, as has Nancy Krieger, professor of social epidemiology, who provided “very honest feedback on everything from precision of results to manuscript edits.”

In her research, Roncarati has found that rough sleepers often get diseases that are similar to the rest of the population, but they have higher rates of death from certain diseases, including cancer and cirrhosis—and they die at much younger ages.

In 2013, Roncarati took a pause in her studies when she had a baby daughter, now 2, with her partner Jim O’Connell, longtime director of BHCHP. She credits O’Connell with inspiring her work in human services and with understanding the importance of researching homeless populations to help inform strategies to improve their lives. Roncarati said it’s wonderful for her “to work and be partners with someone who shares the goal of improving the lives of some of the most vulnerable.”

Going forward, Roncarati hopes to secure a fellowship or research position to continue her work. She wants to delve more deeply into why mortality rates are so high among rough sleepers. Is it because they’ve been homeless for a long period of time? Or does it have something to do with sleeping outside?

“Hopefully what I find,” she said, “will ultimately help change outcomes for the very sickest among those who are homeless.”

photo of Jill Roncarati: Sarah Sholes