May 30, 2013

Dean Frenk—Julio—and your family; graduating students of the class of 2013, and your families and partners and friends; Miss Liang, for that amazing speech; distinguished members of the faculty; all members of the entire School of Public Health community:

Thank you for inviting me to speak to you today.

It’s a pleasure to see some familiar faces and friends here today. I’m happy to see John Brownstein, from the Harvard Medical School and Flu Near You, who we’re partnering with on some really interesting work on digital disease surveillance. John is proof that you can be a PhD and do practical things in public health.

I particularly want to welcome Andy Epstein. You may have known her husband Paul Epstein who sadly died a year and half ago. Paul Epstein founded the Harvard Center for Health and the Global Environment. He taught classes at the School of Public Health on climate and health and he set the gold standard for combining science and advocacy…and love.

Paul and Andy and my wife Girija and I came together when we were interns in San Francisco around the time of the Summer of Love. You may have heard about it in your history books.

Coming here today I’ve been thinking about that time, in the late 60’s and 70’s when Paul and Andy and Girija and I were activists. We had dedicated ourselves to change the practice of medicine, to make health care work for the poor, the vulnerable, the weak. We were activists and we were optimists.

All of you are at some level activists, at some level optimists. Do you remember the first time you decided on a career in public health, in serving the people, as an activist for social justice?

I know the very minute the virus of activism infected me.

On Nov. 5, 1962, the Reverend Martin Luther King visited the University of Michigan. It was a dramatic time. The world teetered on the brink of nuclear madness during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Federal troops were on patrol after the first black student was admitted to Ole Miss. And Bob Dylan was singin’ “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall.”

I was a completely clueless sophomore, locked in my own selfish bubble. But I went to hear Martin Luther King as he spoke that day in a way that made us feel it was our destiny to become activists. We jumped on stage and stayed there as his soaring rhetoric and the truth of his life, his example, called everyone who heard him to a life of service to social justice, a life that for me became public health.

A small group of us sat around him for several hours, listening, mesmerized. We could not let him go.

He said that “the arc of moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice” He was not the first to speak of the arc of the moral universe bending towards justice. Albert Einstein talked of it. Theodore Parker, a Unitarian Minister, was probably the first. Fittingly he lived not far from where we sit, in Boston. Fittingly, he was an abolitionist, a changemaker, an activist. A troublemaker of our kind.

But for me, when I heard Martin Luther King say, “The arc of the moral universe is long but it tends towards justice,” it might have been the anthem of the 60’s. It struck home. We all signed up for the cause. We marched in Selma, Alabama, Mississippi, and Washington D.C. for freedom, social change, and civil rights. We marched against secret wars in Southeast Asia.

We had sit-ins and teach-ins and joined an alphabet soup of civil rights organizations: CORE, SNCC, and NAACP. We learned non-violence, to sit in at the lunch counter at Woolworth’s, and absorb body blows without hitting back. In medical school, I joined the Medical Committee for Human Rights, which had been started here at Harvard, put on a white coat with an ostentatious stethoscope, and joined a cadre of medical students, nurses, and public health activists and we marched with Martin Luther King, surrounding him as if our white coats could protect him. One day in Chicago, at an antiwar march, hundreds of us were arrested marching with Martin Luther King. It was such an honor to be arrested with Martin Luther King. There we so many of us they could not put us in regular jail. They had to make a pretend jail to keep so many. That’s a lesson for activists who plan to get arrested. Figure out in advance how to go to pretend jail.

We won some and lost some, but we successfully stopped the Vietnam War and passed the Voting and Civil Rights Acts. My generation planted seeds that would later embolden movements for women’s rights and gay rights and yes, we felt that indeed “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it does bend toward justice.”

And that is how I wound up with Paul Epstein and Andy Epstein and half a dozen other activists, deciding we would all do our internships—and perhaps wreck havoc—on the same city. Poor San Francisco, it was not ready for us.

A few days before our internship started, a glossy expensive doctors magazine called World Medical News put a photo of five graduating activist medical students on its cover.

They wrote: “Watch out doctors! Watch out hospitals where they will intern! These young revolutionaries are coming. They will destroy your wealth and privileges.”

I guess they thought they had detected the ringleaders of a conspiracy, and they were not completely wrong. We believed, unlike the AMA of the time, that health care was not a privilege, it was a basic human right. And we believed to deprive anyone of basic health care was immoral as a clinician and as a country. Something about inalienable rights and “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” I still believe that. Don’t you?

I looked at that photo yesterday thinking I was going to see Andy today. I don’t believe we looked menacing at all, just scared kids, like most of my generation—angry about an unjust war, fighting for civil rights.

But the hospital I was interning at thought I was menacing, I guess.

Internships began on July 1st. When I walked into the hospital on my first day that magazine cover picture was everywhere. Hundreds of copies were posted on every bulletin board in the place, each with a bull’s-eye painted around my head. They did not intend that bull’s eye to be a halo!

Several bull’s-eyes had a hypodermic syringe stuck in my nose. Below each one was written: “Presbyterian Hospital Welcomes Its New Revolutionary Intern.” Oh, yes.

And maybe it was a coincidence, but maybe it wasn’t: Instead of the usual intern’s 24 hours on, 24 hours off, the first rotation I was assigned was for 96 hours straight in the intensive care ward. By the end of my 4 days on, I was exhausted, useless, and sure I was making lousy medical decisions and sure the hospital had jeopardized the health of patients to make a political point.

But that was a different era than today, and we were bold. On July 5th we issued a press release. On July 6th we organized an interns and residents union. On July 7th, we went on strike for better patient care. Three days later, the hospital caved in and agreed to our demands for better and more inclusive patient care.

The old guard did not believe that “health care is a right and not a privilege.” Some of those same forces are around today in Congress, trying to undermine or undo the Affordable Care Act. They would exclude 45 million uninsured from getting health care. Who are these people who value profits over public health? They are the same forces that fought the 60’s idea of health as a human right.

I have to admit that though we held the moral high ground, we were very arrogant and pigheaded. Not all of older clinicians saw the anti-war movement and the civil rights movement as a threat to their status. Some looked at us long-haired shaggy hippie doctors and saw a threat to their patients. Once we understood that the middle ground was good and inclusive patient care, we began to work together.

Both sides were right in a way. I soon learned how many of those who were indifferent to the social causes I cared about were actually much better clinicians than me: many worked longer hours, putting their patients’ care at the center of their world.

As for my generation of young radicals, we had prejudged a mostly conservative profession, assuming they couldn’t be good doctors for being out of touch with the great social upheaval of the time, for not understanding the needs of the marginalized, not seeing the patterns and linkages between disease and poverty, the relationship between social justice and life expectancy, and how the battle then as now was about dignity and human rights.

And here is the point as you go forward. Somehow, these two sides of our national health debate—one outward looking at social justice and inclusion and one inward looking inward at high quality patient care that is exclusionary—met then and must meet now on sacred ground, sharing the profound obligation and great joy of improving the health of the people.

The fire of that battle catalyzed great expansion in public health. New areas of study and practice—medical care organization, community medicine, preventive medicine, social medicine—all got created. The EIS corps and epidemiology got a boost when young men could avoid the draft by going to CDC as epidemiologists instead of going to war or going to Canada! The best and the brightest became EIS officers and the CDC became a major player. Much of this centered around Harvard, which played an outsize role in the new alphabet soup of activist public health: MCHR, PSR, SHO, and so many others.

Political activism fueled many public health careers, but in those days there was also the counterculture.

You know of the infamous Alcatraz prison. You may not know that 40 years ago a band of Native Americans invaded, took over Alcatraz, symbolic of their idea of liberating land that once was taken by the US government from the hands of Indians. One woman, a Sioux Indian named Lou Trudell, who was part of that occupation, was nine months pregnant, about to deliver a baby in that cold old prison—where there was no water, no electricity, and no medical care. A newspaper columnist wrote a challenge: Is there no doctor who is willing to go live on Alcatraz and deliver this baby? Of course—I went. I hitchhiked on a local boat, lived on the island with the Indians for almost a month, helped Lou deliver the baby. They named the baby Wovoka after the founder of the Ghost Dance religion. I know that there was no electricity on that cold prison island, but when that Indian baby was born on free Indian land, there was electricity of a different sort. A mystical electricity. It was a deep emotional experience for everyone on the Island, whatever the color of their skin.

After I was lifted by helicopter off Alcatraz to dry land in San Francisco, I was met with dozens of TV cameras asking me “what do the Indians want.” How could I really know? I had never met a Native American until three weeks earlier. Somehow, in a way I still don’t understand, someone at Warner Brothers saw my anxious TV performance and asked me to play a young doctor in a movie called Medicine Ball Caravan—about the Grateful Dead and the Jefferson Airplane and rock bands. I became a rock doc. If you’ve heard the expression “you are either on the bus or off the bus”—I was definitely on the bus. I left medicine for a time to join my dear friend Wavy Gravy’s Hog Farm commune, and traveled on funny painted hippie buses from London to Kathmandu, living for weeks at a time in Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Nepal.

I lament the fact that you can’t take that trip. It was the trip of a lifetime.

My wife and I wound up in a Himalayan ashram for two years. I nearly forgot all about medicine. We studied Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim, Christian, and Jewish texts. And meditated. And that was the normal career path in those days.

My teacher, my guru, Neem Karoli Baba, was a wonderful and very wise renunciate. And we all thought he could see the future somehow. One day, while I was trying to meditate, my guru yelled my name (he called me “Doctor America”). He said it was my destiny to leave the monastery, leave the mountains, to join the WHO team that was being assembled in New Delhi to eradicate smallpox. He said smallpox would be eradicated, that it was God’s gift to humanity to lift one form of suffering from our shoulders, it was God’s gift because of the dedication of public health workers. How he knew smallpox could be, would be eradicated, I will never understand. And I was 27 and had never seen a case of smallpox, and this was to be my first real job out of medical school.

The first time I saw a village full of people dying of smallpox, it was like an image from Hieronymous Bosch or an engraving from Dante’s Inferno. But this was real. When I arrived in that infected village in a big jeep with a big UN seal on it, a mother rushed up to the jeep carrying a four-year-old boy. She asked me to heal him. But the boy was long dead. Everywhere there were children coughing, covered with excruciating lesions. Parents standing by helplessly, watching them die. Some places we were told the rivers did not run because they were clogged with dead bodies.

Smallpox was arguably the worst disease in human history. It had killed more than half a billion people—really 500 million—in the 20th century. Two dozen kings and queens and emperors and dictators died from smallpox. Wealth and privilege could not protect you from a truly excruciating death. Pustules and scabs cover every inch of your body.

There were no intensive care rooms, no clinical care—no treatment options—only the fight to prevent the next case. One third of the victims die. There were almost 200,000 cases in India the year we began.

To eradicate smallpox we had to find every case in the world, every virus, without exception, and put a ring of immunity around it. So that’s what we did. Over the next few years, 150,000 health workers visited every house in India searching for hidden cases of smallpox. We made more than one billion house calls. And in October of 1977, I got to the most remote bottom of Bangladesh to see what would be the last human infection in nature of Variola Major—the end of a chain of transmission of the disease that lasted more than 5,000 years, that had killed Pharaoh Ramses himself and might have scarred the faces of many of Jesus’ or Moses’ or Buddha’s disciples. A young girl named Rahima Banu in Bhola Island, Bangladesh. When I saw her after her scabs had fallen, and contemplated that perhaps once when she coughed and the last viruses of Variola major fell on the hot parched land of Kuralia village, the last virus died from that chain of transmission going back to Ramses, to biblical times, I cried like a baby, so relieved, so happy the demon of smallpox was dead, so honored to be a small part of it.

In a way, my life was set. I had not yet gone to public health school, I had not yet studied epidemiology formally, I did not yet have my MPH but I knew I would. And I knew I would always be a public health worker. No matter how hard, no matter the long odds, nothing could be more noble.

My mentor was Bill Foege, the legendary epidemiologist who would go on to head CDC and inspired the Gates Foundation commitment to global health. He crafted the strategy of surveillance and containment that saved the world from smallpox. Bill took me to see my first case of smallpox. Bill is very very tall. We would go into villages to vaccinate kids and look for cases of smallpox. But the kids would all hide. Because I spoke Hindi he told me to tell all the children that the “tallest man in the world had come to their villages.” I did, they came, and we grabbed them and vaccinated them. Bill taught me to take the same sense of personal satisfaction watching the epidemic curve drop as I would have watching a child’s fever chart. Hidden in those dry graphs and charts were the stories of hundreds of thousands of individual life and death struggles.

I spent 10 years in India and Asia fighting smallpox. I had been the youngest member of the WHO smalIpox team. I was the last to leave. I turned off the lights and packed up the archives.

Smallpox was the first and, so far, only disease ever eradicated from the world.

I expect and pray that another ancient disease, polio, will soon follow into the dustbin of history before you finish the first years in your new careers. Thanks to WHO and Rotary and the Gates Foundation for sticking with polio, despite the murder of public health workers in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Plus, the Carter Center has such success in another eradicable disease—another ancient biblical disease—called Guinea worm or Dracunculiasis or “the fiery serpent.” Dracunculiasis is written about in the 2nd century B.C. Greek and Egyptian chronicles.

It is a great race to see which of these two ancient scourges will be eradicated first! Polio and Guinea worm, each endemic now in only three or four countries: maybe it will be a photo finish. That would be nice. Because if smallpox is the only disease in history eradicated, it will always be an anomaly, an anecdote, a footnote—but if two or three diseases have been eradicated, that will be a huge boost to global public health workers all over the world.

And then we can go after pandemics. With the new digital disease detection systems like Healthmap and GPHIN and ProMed and Google Flu Trends and Flu Near You and new governance systems like CORDS, I have high hopes we can end pandemics in your lifetimes. It sounds crazy—but so did the idea of eradicating smallpox or polio. This is another race—between inevitable pandemics if we do nothing, and the new technologies that could put pandemics in the same dustbin of history where we have this image of smallpox, polio and Guinea worm sitting in that dustbin, waiting for company.

After we eradicated smallpox, some of the smallpox warriors as we fancied ourselves wanted to do it again, and we started the Seva Foundation to apply the same kind of scale to giving back sight surgically to poor blind people. We took what we learned in smallpox eradication and raised funds from old friends like Steve Jobs. By driving the price of a sight restoring operation to (then) $5, we could deliver service at scale to anyone in the world. Seva, and our partner, the Aravind Eye Hospital, have restored sight to more than 3 million people.

So that’s my story.

Today begins your story, your turn.

Your generation, your adventures. And public health is a great adventure, filled with so many possibilities. If you want, you can work on a much larger scale than individual doctors. Or you can work with a small local health department. Either way you will find joy and satisfaction in your chosen field of public health.

You may fight for animal rights or human rights.

You may work on poor eyesight or mental illness or you may crack the epidemiological or genomic mysteries of cancer or heart disease.

You may challenge the government, corporations, or special interests to right wrongs local or global.

You may seek to lessen the burden on the poor, or battle to bring water, health care, and education to those who need it.

You are a changemaker, part of the warp and weft of social change. You are pathfinders. Whether you work on improving the social justice of public health, like Paul Farmer, or fight the terrible effects of climate change on health, like Paul Epstein, you can be a public health hero.

When you work on public health, when you choose the noble path of working for the health of the public, you inherit the great tradition of those who came before you.

Class of 2013: I wish you amazing, transformative lives and adventures, filled with inspiration, hard work, equanimity, and joy.

Class of 2013: Today you inherit a magnificent tradition and embark on a noble cause.

Every single day, you’ll have the power to change lives.

You’ll give hope and health to your communities and your world, even when the news is bad.

In the 60’s, when my generation was shell-shocked by the assassinations of Martin Luther King, John F. Kennedy, and Robert Kennedy, and the daily death toll from the war in Vietnam depressed us beyond imagination, a San Francisco radio reporter, Skoop Nisker, ended every news broadcast by urging his listeners, “The news is bad today. But if you don’t like today’s news, go out and make some of your own.”

Class of 2013: From today on, make your own news. The narrative of history is now in your hands.

Class of 2013, new members of the public health community, congratulations! Your teachers, your parents, your partners, and all of us who went ahead of you are proud of you.

I just have one parting request. Listen up!

Whether it was Dr. King or someone else who first imagined the arc of the moral universe bending towards justice, you can be damn sure they did not mean that history bends toward justice all on its own. Look around you. It is far from automatic. It is a battle for the poor, a battle for justice, a battle to lift the health of the public.

Here is what I ask of you: Imagine that arc of history that Martin Luther King inspired is right here with us. The arc of the universe needs your help to bend it towards justice. It will not happen on its own. The arc of history will not bend towards justice without you bending it. Public health needs you to insure health for all. Seize that history. Bend that arc. I want you to leap up, to jump up and grab that arc of history with both hands, and yank it down, twist it, and bend it. Bend it towards fairness, bend it towards better health for all, bend it towards justice!

That’s your noble calling of public health. Welcome.

And thank you.

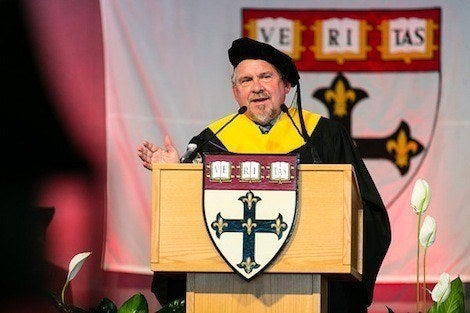

photo: J.D. Levine