February 2, 2016 — In the wake of the devastating Ebola epidemic of 2014-15 in West Africa, which killed more than 11,000 people and cost about $2.2 billion, an international commission has outlined an ambitious agenda—at an annual cost of $4.5 billion—aimed at readying the world for the next global health crisis, whether it’s a resurgence of Ebola, SARS, or bird flu, a swiftly moving threat like the Zika virus, or some entirely new disease.

The commission’s report, published January 13, 2016 in the New England Journal of Medicine, urges sweeping improvements in nations’ public health capabilities and infrastructure, in international leadership for preparedness and response, and in research and development related to infectious diseases.

Read a NEJM article about the report.

“The Ebola crisis has spawned a huge amount of reflection in the global community,” said Margaret Kruk, associate professor of global health at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who served as a reviewer for the report, which comes on the heels of two other post-Ebola reports—including a joint report issued last November by the Harvard Global Health Institute (HGHI) and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (known as the Harvard-LSHTM report).

Each of these reports has drawn similar conclusions: that the world must respond more quickly and more effectively to potential pandemics. The new report is notable because it focuses on how improvements will get implemented and who should be responsible for them, said Kruk. Although many countries have previously agreed to boost their public health capabilities, “very few have delivered, and there’s been no really serious monitoring of this in the past,” she said. “So the new report’s focus on implementation and measurement is really important.”

Ashish Jha, HGHI director and K.T. Li Professor of International Health at Harvard Chan School, who served as co-chair of the Harvard-LSHTM report, added that the new report “stands out in its concrete discussion of funding necessary to propel these recommendations forward.”

The report was produced by a 17-member international group called the Commission on a Global Health Risk Framework for the Future (GHRF), led by Peter Sands of Harvard Kennedy School. Commission members—experts in finance, governance, research and development, health systems, and social sciences—included former Harvard Chan School Dean Julio Frenk, now president of the University of Miami; and Paul Farmer, Kolokotrones University Professor at Harvard and cofounder of Partners in Health.

A growing threat

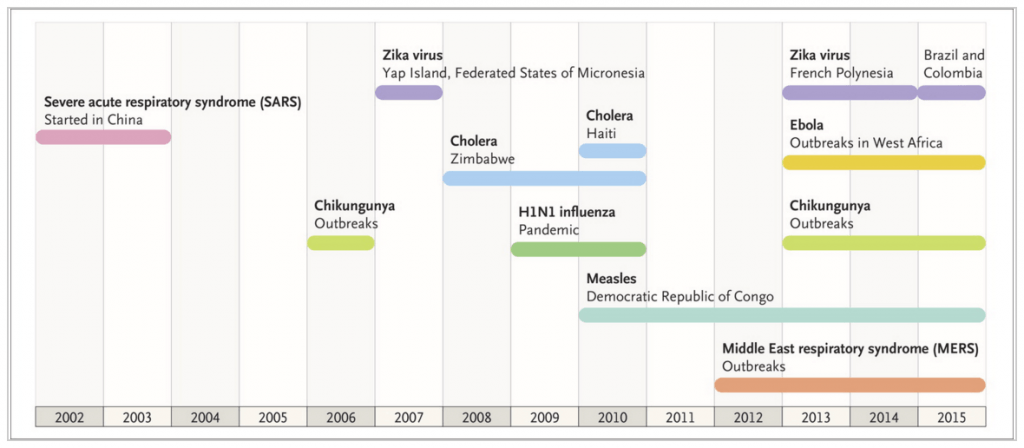

According to the report’s authors, crises like the Ebola epidemic are increasingly likely given the world’s growing population, greater animal-human interaction, economic globalization, environmental degradation, and ever-increasing human interactions across the globe. Future outbreaks could cause not just massive loss of life but also huge economic disruption, the report said; for example, another global pandemic on the scale of the 1918 influenza outbreak, which killed 50-100 million people, could cost the world more than $60 billion.

The world is currently ill-equipped to deal with such a crisis, the report stated. But if the global community would commit $4.5 billion annually—roughly 65 cents per person—the world would be better protected from future crises, the report said.

While that may seem to be a hefty pricetag, Jha said that “given the size of the threat to humanity, economic productivity, and social cohesion, this is a trivial degree of investment. A few billion in pandemic preparedness is cheap compared to the cost of not being ready for the next disaster.”

Boosting health systems

One of the report’s key recommendations is that national governments boost their public health infrastructure and capabilities according to a common standard by 2020. Improvements should include an adequately trained workforce that can quickly detect and respond to outbreaks.

For some countries, meeting this goal will be a big challenge, Kruk said. “Some countries—including Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, the three that were hardest hit by the Ebola epidemic—have such a long way to go on every element of response to a potential pandemic,” she said. “Many of these countries are funded very extensively by foreign assistance, and that funding has created a health system that deals with malaria very well and has done a pretty good job in child health, but there’s not really a multifunctional, resilient health system.”

Sounding a hopeful note, Jha said, “There’s finally a realization among nations that the status quo is not acceptable. Ebola was devastating in the three most affected West African countries. No one wants to go through that again.”

Leading the response

The World Health Organization (WHO) is the logical organization to take the lead in responding to future pandemics, but must boost its capability, resources, and leadership to do so effectively, the report said. Among its recommendations: WHO should establish a daily high-priority “watch list” of disease outbreaks with potential to become epidemics and create a Center for Health Emergency Preparedness and Response (CHEPR), sustained by increased contributions from member states. Already, WHO has approved the creation of CHEPR and the new center’s work has begun.

Making WHO more independent and effective will be a challenge, according to Kruk and Jha. WHO’s central leadership, member states, and regional offices all have influence over the organization’s efforts and, according to Jha, there’s constant jockeying among these power centers—which can make it difficult for the organization to be nimble in the face of a swiftly moving epidemic. It will be important in the future for WHO to exercise more effective leadership in spite of its distributed governance structure, Kruk and Jha said.

WHO’s budget is another problem, Jha added. The organization’s funding comes from member states, but most states earmark that funding for particular purposes, which can limit WHO’s ability to respond to new health crises. “The earmarks represent a lack of trust on the part of member states that WHO will use the money wisely,” he said. “But if WHO can show greater effectiveness in its ability to respond to pandemics and other threats, it will help restore the trust that WHO often lacks, leading to more appropriate, dedicated funding.”

An emphasis on accountability

Both Kruk and Jha praised the new report for its emphasis on making nations accountable for improving their health systems, and for recommending that international aid and financing be withheld if nations don’t comply.

“There’s a clear message to countries at risk for pandemics that they have to get their house in order if they want more grants and loans from the international community,” Kruk said. “If ministers of finance—who determine health budgets and health investments—see a threat to their financing, they’re much more likely to take action.”

She added, “Sometimes reports like this can sink like a stone and never be heard from again. But the visibility of this issue is so high that this report has a better chance than most of retaining relevance and hopefully guiding action.”

“There has been so much convergence in the last couple of months, given that three major reports have now been issued in the wake of the Ebola epidemic, and there is broad agreement between them,” said Jha. “There is now clear momentum to make meaningful changes. Hopefully, when the next global health crisis occurs, the world will be better prepared.”

Photo: CDC