For immediate release: September 11, 2023

Boston, MA—Increasing energy efficiency in buildings can save money—and it can also decrease the carbon emissions and air pollution that lead to climate change and health harms. But the climate and health benefits of reducing buildings’ energy consumption are rarely quantified.

Now, researchers from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston University, and Oregon State University have developed a new method for calculating the health and climate impacts of these energy savings.

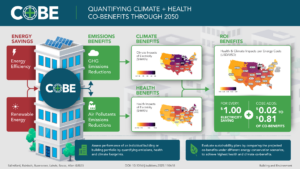

The new methodology, described in a September 8 paper in the journal Building and Environment, is part of a four-year project called “Co-benefits of the Built Environment” (CoBE). Initial work with CoBE focused on calculating country-level health and climate benefits of energy savings in buildings; the newly developed method can be used to assess those benefits on a regional, municipal, or individual-building scale.

“The decisions we make regarding our buildings are directly impacting our climate and our health,” said Joseph Allen, associate professor of exposure assessment science at Harvard Chan School and senior author of the study. “CoBE is an important advancement for two reasons: It adds a health lens to what has largely just been a carbon conversation, and it allows us to peer into the future so we can optimize decision-making today regarding the impact of energy-efficiency measures in buildings.”

The new methodology—available for public use via a tool on the CoBE website—enables building owners, operators, and investors to easily make future projections, through the year 2050, about the climate and health co-benefits of their energy decisions. The CoBE website explains how the tool works and includes a blog, FAQs, case studies, and videos to help guide users.

To use the online tool, building owners or operators input key information about a particular building or set of buildings—such as location, size, energy sources, and energy consumption. The tool calculates the building’s energy and emissions footprints, as well as climate and health impacts in dollar values. Users can then use the tool to estimate co-benefits under different energy use scenarios.

The CoBE tool uses various models and datasets in making its calculations. To project emissions reductions from energy savings, CoBE uses energy and emissions projections from the U.S. Energy Information Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency. To quantify climate impacts in monetary terms, CoBE uses the Social Cost of Carbon, a tool developed by the U.S. government Interagency Working Group that monetizes the long-term impacts of every ton of greenhouse gas emissions. To quantify health impacts, CoBE estimates premature deaths caused by exposure to fine particulate air pollution (PM2.5)—one of the most harmful types of pollution caused by fossil fuel combustion—as well as their associated health costs.

“Health benefits often go unvalued in decisions around energy strategy, carbon offsets, and other carbon emissions reduction measures,” said co-author and CoBE project co-PI Jonathan Buonocore, assistant professor of environmental health at Boston University School of Public Health. “The CoBE tool can put a monetary value on the health benefits of emissions reductions.”

To demonstrate the utility of the CoBE tool, the co-authors designed a case study modeling the effect of a hypothetical reduction in electricity use among buildings across the U.S. from 2018 to 2050. They found that a building’s geographic location would play an important role in determining the health and climate impacts from reductions in energy use. For example, for every dollar of electricity savings in 2018, one region in Wisconsin and Michigan would see $0.52-$0.70 in health and climate co-benefits due to the reduced use of energy supplied by fossil fuels. Overall, in the year 2050, for every dollar of electricity savings, there would be another $0.02-$0.81 of additional savings in health and climate co-benefits.

“The CoBE tool provides a user-friendly way for decision-makers and other stakeholders to assess their current performance and to quantify health and climate co-benefits of different energy conservation scenarios, to improve the health and well-being of people and our planet,” said lead author and CoBE project co-PI Parichehr Salimifard, assistant professor of architectural engineering in the College of Engineering at Oregon State University.

Harvard Chan School co-authors of the paper include Marissa Rainbolt, Mahala Lahvis, and Brian Sousa.

The study was supported by Login5 Foundation.

“A novel method for calculating the projected health and climate co-benefits of energy savings through 2050,” Parichehr Salimifard, Marissa Rainbolt, Jonathan Buonocore, Mahala Lahvis, Brian Sousa, Joseph G. Allen, Building and Environment, September 8, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110618.

Visit the Harvard Chan School website for the latest news, press releases, and multimedia offerings.

Top image: iStock/ArtShotPhoto

For more information:

Maya Brownstein

mbrownstein@hsph.harvard.edu

###

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health brings together dedicated experts from many disciplines to educate new generations of global health leaders and produce powerful ideas that improve the lives and health of people everywhere. As a community of leading scientists, educators, and students, we work together to take innovative ideas from the laboratory to people’s lives—not only making scientific breakthroughs, but also working to change individual behaviors, public policies, and health care practices. Each year, more than 400 faculty members at Harvard Chan School teach 1,000-plus full-time students from around the world and train thousands more through online and executive education courses. Founded in 1913 as the Harvard-MIT School of Health Officers, the School is recognized as America’s oldest professional training program in public health.